Case

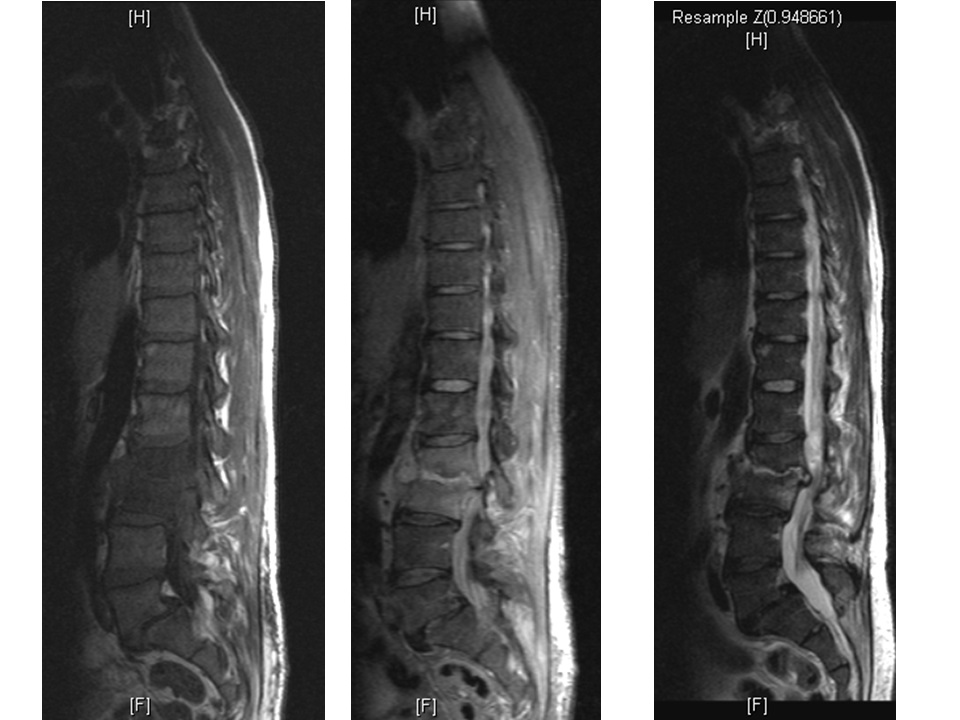

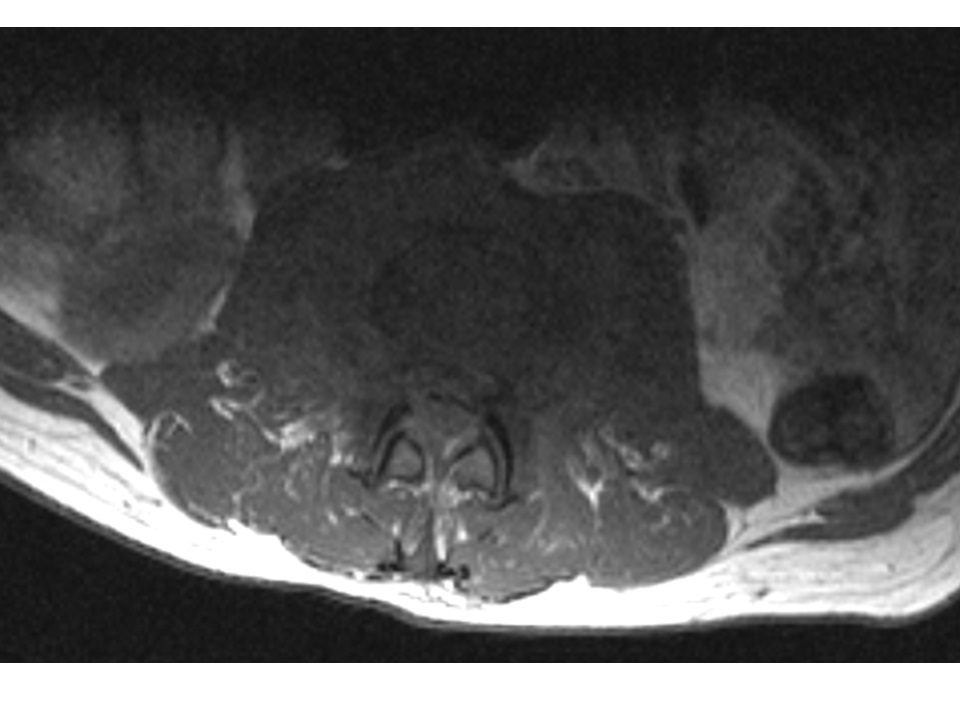

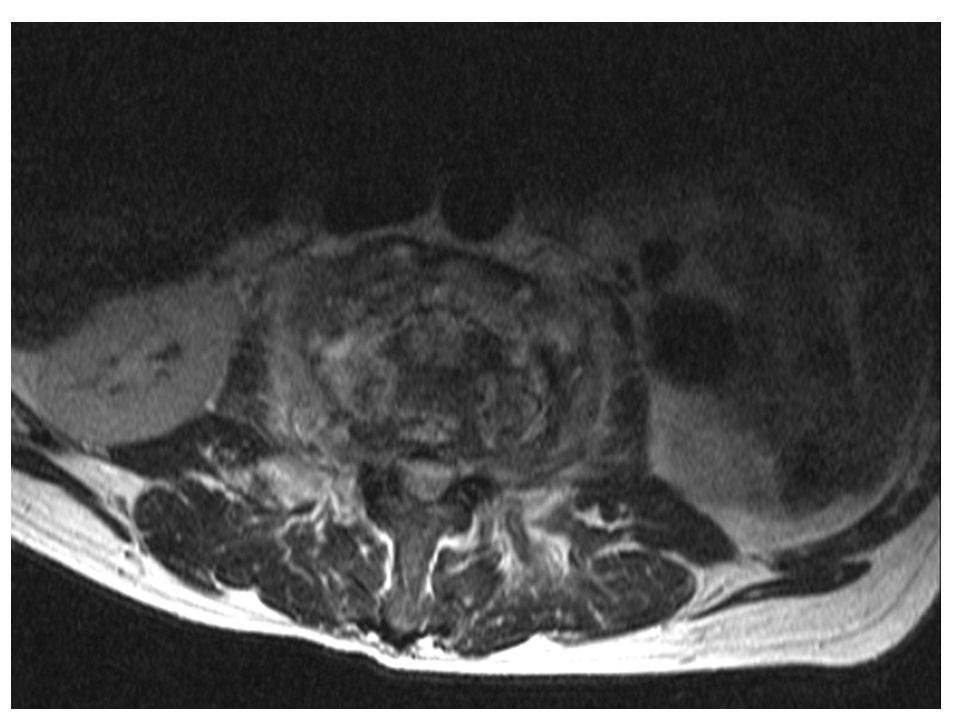

A 52-year-old male with a background history of tablet controlled diabetes and a smoker for 30 years, presented with a two-week history of gradually increasing back pain radiating into both thighs. The pain was severe at presentation to the A&E. The pain was worse with standing and walking and relieved partially by sitting and completely by lying down. His neurology was normal and he did not have any systemic features. His CRP was 112, white cells were marginally elevated and his MRI show the typical features. Fig 1a shows the sagittal views with T1 weighted image (left) with a loss of anatomic definition between disc, end plate and vertebral body with hypo-dense signal. STIR sequences (middle) and T2 weighted images (right) show the increased signal from the disc space at L23 and the vertebral bodies of L2 and L3. The axial sections (1b, c) show that there is no epidural collection and that there is a significant anterior soft tissue enhancement.

This patient was treated with antibiotics for three months and was given a lumbosacral orthosis for the same period of time. He pain gradually improved, CRP normalised and returned to un-restricted activities in four months

Figure 1a

Figure 1b

Figure 1c

The problem

Discitis is an infection that starts in the disc space and comprises of a continuum of a spectrum that includes vertebral osteomyelitis. The seeding of the infection is commonly by a haematogenous spread. Due to the unique vascular anatomy, infections primarily involve the disc space in young children and the vertebral body in adults. The valveless Batson’s plexus – a network of veins in the body – provides a natural portal for gastrointestinal and genitourinary organisms to inoculate the lumbar spine. Staphylococcus aureus is the commonest organism implicated. Gram negative organisms, streptococcus and tuberculous bacilli, MRSA and fungi are the other organisms seen. Extension of the infective process into the epidural space as an abscess, vertebral collapse and instability, can lead to a neurologic deficit by direct compression or a vascular insult.

Features

Young child: Discitis is a rare cause of back pain in young children. Studies have found that the majority of cases affect children up to three years old.1 The pain can be severe, associated with a refusal to walk, limping and abdominal pain. Some children present acutely with fever, systemic effects, paraspinal muscle spasm and guarding. Neurologic deficits are unusual, unless in the presence of an epidural abscess.

Features to look out for in children include:1

- Limping, with hip or leg pain

- Back pain

- Pain-free limb weakness

In studies looking at children who have presented to hospital with the condition, blood results have shown a raised ESR (over 20mm/hour in 80% of children with discitis).1

Adult: Primary discitis/vertebral osteomyelitis is a differential for back pain in adults. In patients over 50 years of age it is twice as common in males. It is more common in certain high risk groups such as advancing age, malignancy, rheumatoid disease, diabetes, end-stage renal disease, UTI and immune deficiency. Bacteraemia may occur following dental procedures, intravenous drug administration (medicinal or illicit), renal stenting, GI endoscopic procedures and cardiac/vascular interventional procedures. Clinical effects may be restricted to back pain without systemic changes, if the immune system is impaired. Neurologic deficits are seen in 3-4% of the cases due either to an epidural abscess, instability with collapse or vascular compromise.

Post-operative: Discitis can result from direct inoculation of the disc space following needling procedures such as a discogram or open surgery. This presents as an inordinately lengthy period of post-operative pain. The pain is out of proportion to the clinical findings and the expected recovery following the operation. It may also present a new or an increasing neurologic deficit.

Diagnosis

Bloods: CRP is a useful acute phase reactant that is raised early in the process and is a useful marker of the disease and of the recovery. White cell count and ESR may not be as reliable. Blood cultures are positive in 50–75% of the cases, particularly when systemic features are severe.

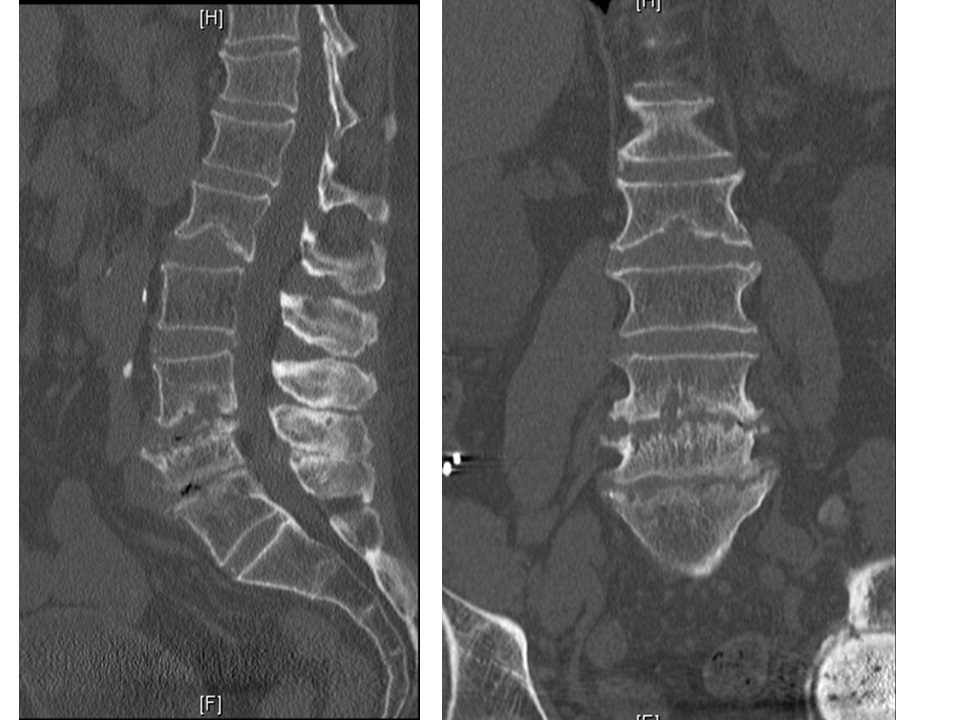

Imaging: Plain radiographs lag behind by a few weeks in diagnostic reliability. However, erect radiographs are useful is assessing spinal stability. MRI is a useful primary and a follow-up diagnostic tool. It has a high sensitivity and specificity. Full spine MRI is recommended to identify skip lesions. There is a loss of definition and blurring of the margins between the disc space, end plates and the vertebral bodies. MRI also provides a clear evaluation of epidural abscesses. Though bone scans (technetium, gallium and indium) have been reported as diagnostic tools with a high sensitivity and low specificity, they have been largely replaced by CT with SPECT scans. In selected cases, CT scans provides useful information of the bone destruction and likely instability.

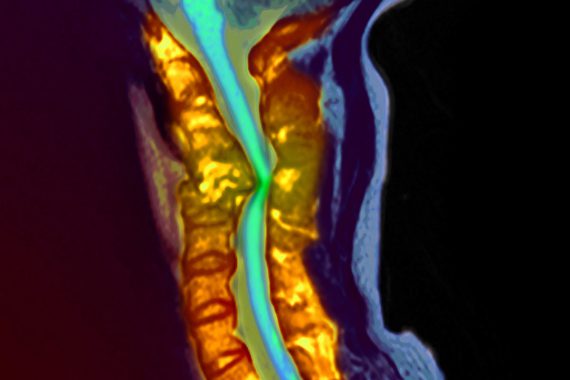

Figure 2a

Figure 2b

Management

Although identifying an organism is not always possible, an attempt is helpful in targeting antibiotic therapy. In the absence of an available organism or with unknown sensitivity, empirical treatment is started. Initially, intravenous therapy is followed by oral antibiotics for up to three months. Microbiological consultation guides the type, duration, dose and route of administration of the antibiotics.

Anti-inflammatory pain medications help reduce the pain. Mobilisation may be allowed as pain permits with a suitable brace immobilisation. Close monitoring of spinal stability with erect radiographs is mandatory particularly in cases with associated vertebral osteomyelitis. A close monitoring of the neurologic status, monitoring of liver function while on antibiotics and of the cardiac status to rule out infective endocarditis.

Evolving or a new neurologic deficit is an absolute indication for surgical intervention. Severe pain, ineffective medical management and fulminant sepsis are relative indications for surgery. Surgery includes local treatment such as obtaining biopsy and culture samples, local debridement, achieving stability, decompressing the neural structures and re-aligning the spinal column. Surgery is usually an adjunct to the medical management.

Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment usually leads to a favourable outcome. Late collapse and instability may lead to mechanical and neurological effects requiring delayed intervention.