A fit and well 58-year-old woman presents to her GP with a swelling ‘underneath the tongue’ that she has noticed over the previous three months. Over the past week she has noticed some mild pain ‘on and off’ in this region but this has been unrelated to mealtimes. She denies having any foul taste in her mouth. She has no relevant medical history, has never smoked in her life and rarely drinks alcohol.

On examination, a firm, non-tender and non-fluctuant 2cm lump is palpable in the left floor of the mouth. On bimanual palpation of the floor of mouth and submandibular regions, clear saliva can be produced from both left and right duct orifices. Routine blood tests including FBC, U&E, ESR are unremarkable. The patient is referred urgently to the local oral and maxillofacial department and a diagnosis of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the sublingual gland is made.

The problem

About 80% of salivary gland lumps occur in the parotid gland, of which 75-80% are benign and most are pleomorphic adenomas (see picture on page 66). However, as a general rule to remember, the smaller the salivary gland, the more likely a neoplasm is to be malignant. It is important, therefore, to recognise that tumours of the sublingual gland, being the smallest of the major salivary glands, are more likely to be malignant than benign – approximately 60% versus 40%.

Submandibular glands, being of moderate size, are only slightly more likely to be benign than malignant. Solid minor salivary gland tumours (of the palate or upper lip for example) however, being the smallest, are malignant in the vast majority (more than 80%) of cases. Always take an upper lip lump seriously, whereas almost all lower lip lumps will be simple mucoceles.

There are numerous forms of salivary malignancy but, in the sublingual gland, adenoid cystic carcinoma is the most common, followed by muco-epidermoid carcinoma. The underlying pathology is irrelevant but what is important is the anatomical location of the swelling, which has a significant bearing on the likelihood of malignancy.

Risk factors for adenoid cystic carcinoma of the sublingual gland are uncertain and patients frequently have no history of conventional risk factors for oral malignancy, such as smoking or alcohol intake.

Features

Salivary gland malignancies are fortunately relatively uncommon and a firm lump in the substance of the floor of the mouth is more commonly due to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). However, such tumours usually start as an ulcer, which becomes indurated and patients commonly have a history of smoking or alcohol intake – not the case in this patient. Consequently, a firm swelling in the substance of the sublingual gland without classical features of SCC is more likely to be a malignant salivary neoplasm.

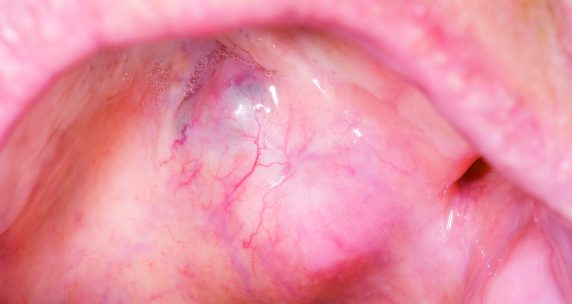

Benign, non-neoplastic salivary swellings of the floor of the mouth are commoner than sublingual gland tumours and these would include a ranula (floor-of-mouth mucocele) and a salivary stone (sialolith) in the submandibular (Wharton’s) duct.

A ranula is an outpouching of salivary apparatus from the sublingual gland and may be congenital or acquired (for example, secondary to trauma, infection or surgery) in aetiology. However, a ranula is typically soft and fluctuant rather than firm. Stones in the submandibular duct are very common and these are often visible as yellowish swellings in the floor of the mouth.

Due to obstructive effects on both the sublingual and submandibular gland, the patient may experience swelling and pain in both regions, which becomes worse at mealtimes. With frank obstruction, infection often ensues and the gland becomes completely obstructed such that saliva cannot be easily milked from the duct orifice. These classical features were not apparent in this case study, making a malignant salivary neoplasm all the more likely.

Swellings of the larger major salivary glands may be malignant, but are more likely to be benign. Sinister features warranting urgent referral for a suspected malignancy would be the presence of facial nerve palsy (parotid malignancy) or hypoglossal/lingual nerve deficit (deviation, weakness or numbness of the tongue for invasive submandibular gland malignancy). However, nerve deficits are late signs. Consequently, for any progressive, hard/firm, fixed lump (especially if present for more than three weeks) or in the presence of lymphadenopathy or risk factors such as smoking and alcohol, an urgent cancer referral would be appropriate.

Benign swellings do not, in general, have the associated sinister features listed above and are typically softer and more insidious in onset.

Investigation

There is little a GP can do to investigate a suspected salivary malignancy. Routine blood tests may show signs of infection if obstructive features are present -this is the case in both benign and malignant disease. However, careful clinical examination with bimanual palpation and meticulous assessment of the rest of the head and neck for other abnormalities is key.

Diagnosis is reliant on imaging (MRI) and biopsy with fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) under ultrasound guidance or open biopsy under local anaesthetic if easily accessible through the oral route.

Diagnosis

Once salivary malignancy is confirmed by FNAC, local and regional staging and tumour evaluation is commonly undertaken using MRI. Ultrasound is also useful for assessing the neck with rounded nodes often being pathological, compared with normal or reactive nodes that are kidney-bean shaped. These lymph nodes can often be identified at the time of ultrasound-guided FNAC of the salivary lump itself, with FNAC done on any nodes that look worrying. As with other head and neck malignancies, CT scanning of the chest is used to assess for distant metastases.

Management

Ultimately, the treatment of choice for salivary gland malignancy is surgical excision, with or without neck dissection for regional tumour control. Adjuvant radiotherapy is commonly used after surgery to improve cure rates.

From the GP’s point of view, the history and examination, alongside recognition of benign versus malignant aetiology at different salivary gland sites is pivotal in identifying these uncommon and sometimes insidious malignancies. Urgent referral routes should be used for any patient with an unexplained lump lasting for more than three weeks, and certainly in the presence of the sinister features discussed above.

Mr Alex Goodson, Mr Arpan Tahim and Mr Karl Payne are specialty registrars in oral and maxillofacial surgery at University College Hospital, London, and

Author credit

Professor Peter Brennan is a consultant maxillofacial/head and neck surgeon at Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth

The authors have recently published a book entitled Important Oral and Maxillofacial Presentations for the Primary Care Clinician, which has been sent to every GP practice in the UK. It contains algorithms providing guidance for the management of many head and neck conditions, including neck lumps and malignant disease. The book was written in collaboration with the RCGP. Further copies are available at cost price (£12.50) from Amazon.