Prescribing for people affected by osteoarthritic pain has considerably changed in the past decade, but not in the direction you would expect from biomedicine, a system which is commonly associated with progress. Prescribers know about the adverse effects of their workhorse drugs on blood pressure, kidney function, mental state, liver function, lucidity and social engagement, but they don’t know to what extent it will affect the patient.

Current standard treatment

Current standard treatment includes a combination of lifestyle advice, repeat medication and acute medication for flare-ups, plus courses of active exercise-based physiotherapy in response to pain episodes.

Standard treatment may range from a form of arguably benign neglect – ‘normalisation to old age’ – to thoughtful proactive care, which focuses on patients’ values and individually negotiated goals.1,2 NICE suggests a stepped-care model.3 This model, visualised as a simplified dartboard, features exercises and education in the bull’s eye. Its essential aim is the teaching of skills in order to enable people to help themselves. Paracetamol in regular doses and topical NSAIDs are added to the core treatment as simple measures. Further options are situated in the outer ring and include steroid injections, opioids etc.4

Steroid injections are safe, but monotherapy with injections may mean that the effects of active therapies are not harnessed and the habit of needing injections may develop. There are no hard and fast rules about the maximum number of injections and their consequences.

What’s newly available

‘Tear, flare and repair’, as a concept of dynamic remodelling.5 Framing the role of repair processes in and around the joint is a step towards minimising semantic harm and inviting the patient to support these healing processes by engaging in protective behaviours. Promoting this positive attitude is part of the musculoskeletal core skill training for GPs and reflects the need to need to provide patient with accurate information and maintain a positive approach .6

The past decade has seen a rise in topical NSAIDs use, mainly due to the better safety profile in comparison to oral NSAIDs, and increased use of opioids in low doses to treat chronic non-cancer pain. Capsaicin as topical treatment has enhanced the therapeutic options, and has been mentioned in the updated NICE guidelines.

What has fallen out of fashion and why

COX-2 inhibitors fell out of fashion in 2004 after their adverse effects on cardiovascular risk emerged, but occupy a niche as a second (or third) line option in the drug management of OA. NICE decided to keep the 2008 recommendations in place – that COX-2 inhibitors should be considered only if paracetamol or a topical NSAID are ineffective for pain relief – until a full review of over-the-counter and prescription-only drugs has been completed.

Chondroitin and glucosamine in various preparations and dosages are part of the prescribing folklore. They are often purchased OTC as part of individual self-care strategies and sometimes make it on to NHS-funded FP 10 prescriptions. The quality of the data to support the effectiveness of these preparations is poor – sample sizes are small and outcome criteria regarding changes in structure and symptom reporting are inconsistent.7

Oral NSAIDs, apart from naproxen, are rarely prescribed as regular high doses of ibuprofen and diclofenac affect the stomach and kidneys, and have adverse effects on blood pressure. As such, there have been specific concerns about the negative cardiovascular effects of diclofenac.8,9

Paracetamol alone, and in combination with ibuprofen, is linked to gastrointestinal side effects and a reduction in haemoglobin. 10 This led NICE to include a recommendation of not using paracetamol in the consultation draft of the updated guideline, but opposition from professional groups in the musculoskeletal field led to a U-turn in this matter. The main argument for sticking to the recommendation of using paracetamol is the fact that the potential alternative – using stronger analgesics – is even more harmful.

Viscosupplementation has been appraised as inferior to steroid injections, but needing less therapist time for injection therapy. There is also very little information about its use in community settings.11

Long-term opioid therapy has considerable side-effects such as constipation, endocrinological dysfunction, cognitive dysfunction and addiction. This may also occur with higher doses of commonly used weaker opioids, such as codeine-based compound preparations or tramadol.12,13,14

Arthroscopic joint lavage and meniscal surgery for tears, which have been diagnosed by radiological observation and not by their clinical signs, are being questioned by the evidence.15

Special/atypical cases and their treatment

NICE guidelines are modelled on the trial participant population, which means that the patient group with more comorbidities or advanced age is underrepresented. The side-effects of many painkillers have to be weighed up against the existing pill burden, the physiological vulnerabilities and also the administrative requirements to contain the management in primary care in the name of efficiency savings.

People who are very difficult to manage at the top end of the analgesic ladder (MED over 120mg/d), or where concerns are raised regarding the dose escalation of opioids in absence of clinical benefit, should be referred to pain clinics.1 People with morbid obesity (BMI over 40) should be treated in specialist centres.

Non-drug options and their evidence base

Self-management

Self-management is inseparable from good clinical care and not a substitute for care. A recent systematic review concludes that self-management programmes for osteoarthritis results are unlikely to cause harm, and ‘may slightly improve pain, function and symptoms.’17

Exercises

Exercises are the core ingredient of successful management of OA, but there are obstacles towards delivering graded supervised exercise therapy. Exercises are either put on a pedestal or dismissed with the fatalistic attitude of the cynical GP. The combination of aerobic exercises, flexibility, and strengthening yields the best results, and they should ideally be graded, supervised and performed three times per week.18,19 Delivery in group settings has been demonstrated to be cost-effective and can be delivered in economies of scale,20 but the provision of subsidised exercise therapy (‘exercise on prescription’) is patchy and retention figures are moderate.

Current NICE public health guidance seeks to clarify what constitutes good practice in this field. Guidance issued by the Department of Health suggests that older adults (aged over 65 years) should engage in physical activity of moderate intensity at least 30 minutes per day to stay fit. Recommended activities should be linked to daily routines and include strenuous household activities, gardening, cycling, brisk walking, climbing stairs and ballroom dancing.21

Acupuncture

OA of the knee is one of the indications where acupuncturists would claim that their treatment is likely to be beneficial for the patient. The big problem regarding the scientific validity of this statement is whether waiting list or sham-acupuncture is chosen as control. The purist stance looks at efficacy (the performance of the intervention in ideal circumstances) and compares acupuncture with sham-acupuncture, where there is only a minimal difference. The contrast is bigger with routine care as control, but this measures effectiveness, the ‘whole package’ of needling, interaction, expectation, and conditioning, which contributes to the effect of this somatosensory stimulation therapy.

NICE chose a purist stance and didn’t recommend acupuncture.3 SIGN, however, interprets the same research evidence in a pragmatist way and recommends acupuncture for short-term pain relief in the guideline for the treatment of chronic pain.22

TENS

TENS has been forgotten, but it is now readily available and provides self-administered somatosensory stimulation.

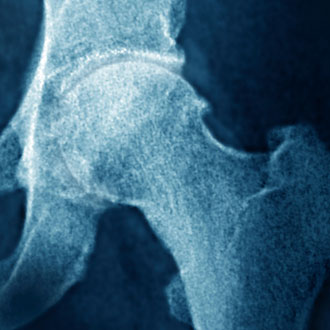

Joint replacement surgery

Joint replacement surgery has its place in the management of OA. Surgical techniques are more refined and tissue-preserving, but there is uncertainty as to the best time to carry them out.

Dr Jens Foell is GP and NIHR Clinical Lecturer in the department of Primary Care and Public Health at Queen Mary University of London and specialises in musculoskeletal medicine.

References

1. Bedson J, Mottram S, Thomas E et al. Knee pain and osteoarthritis in the general population: What influences patients to consult? Family Practice, 2007;24(5):443-453

2. Morden A, Jinks C, Ong BN. Chronic joint pain, self-management and risks: a qualitative exploration of knee pain sufferers’ understanding and management of risk factors. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2011;10(4):462-62

3. NICE. CG177: Osteoarthritis – care and management in adults: London: National Clinical Guideline Centre; 2014

4. Jinks C, Vohora K, Young J et al. Inequalities in primary care management of knee pain and disability in older adults: an observational cohort study. Rheumatology, 2011;50(10):1869-1878

5. Porcheret M, Healey E, Dziedzic K et al. Osteoarthritis: a modern approach to diagnosis and management. Arthritis Research UK, 2011; 10 (Hands On Series 6)

6. Arthritis Research UK Primary Care Centre. Core skills in musculoskeletal care. Chesterfield: Arthritis Research UK in collaboration with RCGP; 2013

7 Busija L, Bridgett L, Williams SRM et al. Osteoarthritis. Clinical Rheumatology, 2010;24(6):757-768

8 Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Wandel S et al. Cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: network meta-analysis. BMJ, 2011;342

9 McGettigan P, Henry D. Cardiovascular risk with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: systematic review of population-based controlled observational studies. PLoS Medicine, 2011;8(9):e1001098

10 Doherty M, Hawkey C, Goulder M et al. A randomised controlled trial of ibuprofen, paracetamol or a combination tablet of ibuprofen/paracetamol in community-derived people with knee pain. Annals of the Rheumatic Disease, 2011;70(9):1534-1541

11. Bellamy N, Campbell J, Robinson V et al. Viscosupplementation for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2006;(2):CD005321

12. Chaparro Luis E, Wiffen Philip J, Moore RA et al. Combination pharmacotherapy for the treatment of neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2012;(7):CD008943

13. Tjäderborn M, Jönsson AK, Ahlner J et al. Tramadol dependence: a survey of spontaneously reported cases in Sweden. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 2009;18(12):1192-98

14. Casati A, Sedefov R, Pfeiffer-Gerschel T. Misuse of medicines in the European Union: a systematic review of the literature. European Addiction Research, 2012;18(5):228-245

15. Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A et al. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus sham surgery for a degenerative meniscal tear. New England Journal of Medicine, 2013;369(26):2515-2524

16. White A, Richardson M, Richmond P et al. Group acupuncture for knee pain: evaluation of a cost-saving initiative in the health service. Acupuncture in Medicine, 2012;30(3):170-175

17. Kroon FP, van der Burg LR, Buchbinder R et al. Self-management education programmes for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2014;1:CD008963

18. Uthman OA, van der Windt DA, Jordan JL et al. Exercise for lower limb osteoarthritis: systematic review incorporating trial sequential analysis and network meta-analysis. BMJ, 2013;347

19. Juhl C, Christensen R, Roos EM et al. Impact of exercise type and dose on pain and disability in knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthritis & Rheumatology, 2014;66(3):622-636

20. Hurley MV, Walsh NE, Mitchell HL et al. Economic evaluation of a rehabilitation program integrating exercise, self-management, and active coping strategies for chronic knee pain. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 2007;57(7):1220-1229

21. Physical Activity Guidelines Editorial Group (PAGEG). Start active, stay active: a report on physical activity from the four home countries’ Chief Medical Officers. In: Health Do, ed. London, 2011:62

22. SIGN. Guideline 136: Management of chronic pain.Edinburgh: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network;2014

Useful weblinks

Arthritis Research UK. Arthritis information. Chesterfield: Arthritis Research UK. Available at: http://www.arthritisresearchuk.org/arthritis-information.aspx