I believe that people with asthma or COPD who are at risk should be given an emergency MDI and spacer pack for effective initial inhaled treatment of future exacerbations.

Alongside Martyn Partridge, I recently published an article in Lancet Respiratory Medicine explaining the reasons for this suggestion (1).

We feel this change in practice would result in better outcomes of exacerbation self-management, and fewer ED attendances and admissions. It might contribute to a reduction in avoidable deaths, and we think this practice innovation has potential applicability worldwide. We want to see the widest possible debate on its merits from Pulse readers, because most care of asthma and COPD takes place in primary care and this is where this suggestion – if agreed – would have to be implemented.

The advantages of this approach would be that:

- Patients would have immediate access in an emergency to the most effective possible method for the self-administration of high dose inhaled treatments.

- Every patient would have been taught how to use these treatments correctly.

- The task of teaching self-management of exacerbations would be greatly simplified for health professionals since there would be one standardized set of advice for the inhaled treatments for asthma and one for COPD.

- This consistency of message – potentially on a national basis – would increase patient confidence and would facilitate widespread public and professional awareness of the key elements of safe and effective inhaled self-management.

- In the context of forthcoming encouragement for a move towards DPIs for routine treatment on environmental grounds this proposal would ensure that patients using dry powder inhalers for their routine treatment retained access to pMDI/spacer for the treatment of exacerbations not responding to usual therapy.

Like all changes in practice, this will take a significant amount of work. We are, however, confident that it would ultimately save time in primary care, both by simplifying the task of self-management education and helping to achieve better treatment outcomes.

Why is self-management failing to fulfil its promise?

Despite effective treatments and longstanding encouragement from guidelines to teach effective self-management skills for exacerbations, research shows that people with asthma and COPD continue to suffer worse outcomes than they should.

There are large numbers of avoidable ED attendances and admissions. Asthma mortality is unnecessarily high, with the recent National Review of Asthma Deaths concluding that a significant proportion of the deaths would have been avoidable with better management. Why is this happening? Why are we failing to implement effective self-management of exacerbations?

There is no single explanation, but we think that one reason is that people with asthma and COPD are not acting appropriately when they are in trouble. Guidelines, based upon numerous good studies, have recommended we teach our patients appropriate first-aid self-management skills and give them action plans. But this approach has been underused.

One reason for this may be that health professionals are uncertain about what advice to give patients about inhaled treatment, and that this is made more difficult with the multitude of different inhalers and regimens now available.

Emergency inhaled treatment packs

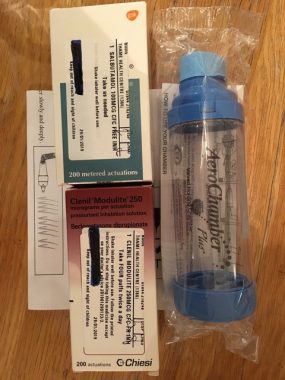

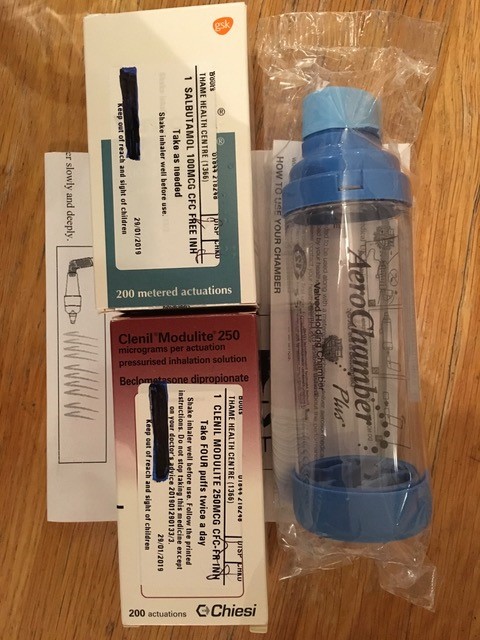

We propose in our article that every person with asthma or COPD who has had or is at risk of having an exacerbation should be provided with an emergency inhaled treatment pack. The pack would consist of a spacer and metered dose inhaler(s) – salbutamol for COPD, and salbutamol and beclometasone 250mcg for asthma – together with instructions for their use. All the evidence strongly suggests that metered dose inhaler with spacer is the most effective way of giving high dose inhaled therapies during initial self management of an exacerbation in the home, but not all patients (or health professionals) are aware of this.

These packs would be sealed and kept separate from the patient’s routine treatment with instructions to contact their primary care team or 111 if the emergency packs were needing to be used, and with advice to seek a face-to-face consultation within 24-48 hours. They should also be available in all primary care and emergency care facilities.

Given the increasing and potentially confusing range of available inhalers, having standard emergency inhaled treatment packs would greatly simplify the task for health professionals of educating patients and parents in emergency inhaled self management at the outset of an attack. Use of the packs should form part of a comprehensive overall written self management plan. Regular anti-inflammatory preventer treatment remains the corner stone of effective asthma management, while multiple interventions are necessary to achieve the best possible outcomes in the regular management of COPD.

Some patients with asthma will also need a reserve course of oral corticosteroid as part of their self-management plan, while some patients with COPD will need reserve courses of antibiotic and/or oral steroids. The proposed packs for the inhaled component of initial exacerbation self management.

Practical considerations

These emergency packs would be provided and their use taught regardless of the inhalers used for routine treatment, which may or may not be the same as the inhalers in the packs. Use of the packs is compatible with MART regimens where these are being used – the packs would only be needed if routine treatment advice has failed.

We think that the dose recommendations proposed for asthma would be valid for both adults and children. The recommended dose for beclometasone – four puffs (1,000mcg) twice daily – is much less than the prednisolone dose that would be used for any attack that did not promptly settle.

We have drafted instruction sheets for using the emergency treatment packs.

Patients should be aware of the expiry dates of the inhaler(s) in the pack. These are usually two-three years from the date of dispensing, and if the emergency pack were unused after this period the need for resupply should be reviewed. Every encouragement would be given that the emergency packs should be kept separate and unopened except in the case of a bad attack. This is to ensure that the materials are available and the inhalers are full at time of need.

The basic NHS cost of an emergency inhaled treatment pack for asthma is approximately £23 and £8 for COPD. These costs would be rapidly offset if, as we think would be the case, there were fewer ED attendances and admissions. Additional prescription costs would be incurred by prescription charge payers but we hope would be considered worthwhile in order to have the best possible inhaled treatment available in case of a bad attack.

Possible concerns with the proposal

It is worth discussing some concerns that may be expressed in connection with this proposal.

The first relates to the safety or otherwise of the high doses of short acting beta agonist necessary for effective initial self management of an exacerbation. There are justifiable concerns about chronic continuing overuse of SABA in asthma. Regular use of SABA over a period if time is a marker of poor asthma control, increased risk of poor outcomes, and the need for more effective regular preventer treatment. Ongoing high SABA use in asthma should prompt early review in primary care. But in an exacerbation high doses of SABA are necessary- are advocated in all national and international guidelines for both asthma and COPD. In asthma they should be accompanied by either high dose inhaled or oral corticosteroids. Remember that one 2.5mg salbutamol nebule contains the equivalent of 25 puffs from a metered dose inhaler. In the context of acute asthma high dose salbutamol as recommended is both necessary and safe provided that patients know the need to use the necessary concomitant inhaled or oral steroid treatment. Patients also need to know when and how to call for help, but we do not think that making effective emergency inhaled treatment available will make it less likely that patients will do this.

Some patients with COPD may be at risk of developing clinically significant tachyarryhthmias or angina when using high dose inhaled bronchodilators, but the salbutamol dose recommended is less than that contained in one nebule, and the risk has to be balanced against that of undertreatment of a COPD exacerbation.

Another issue to discuss is the growing awareness of the need to reduce the environmental impact of respiratory treatments. Currently the hydrofluoroalkane propellants in metered dose inhales have a global warming potential (GWP) many times greater than carbon dioxide. New low GWP propellants for MDIs are under development but will not be available for several years. Dry powder inhalers have a lower environmental impact, but become relatively ineffective in exacerbations. The proposed emergency treatment packs can be given regardless of the inhaler type used for routine treatment, and inhaler recycling schemes need to be made available for unused expired MDIs.

If we are truly concerned about sustainability and green healthcare, we need to consider not just the issue of propellants – and plastic waste – but also the waste and environmental damage caused by poorly-managed asthma and COPD, This leads to time off work and school, unnecessary use of unscheduled healthcare, and unnecessary trips to hospital and clinics. These are resources which would be saved if we taught patients more effective self-management – both for routine treatment and for exacerbations.

Conclusion: An evidence-based proposal that is compatible with guidelines

The elements of this intervention – self-management plans, high-dose salbutamol by spacer in asthma and COPD exacerbation, high-dose inhaled steroid in asthma exacerbation – are not new, and each have a strong evidence base. They are already widely advocated and are often effective when correctly implemented. What is new is a proposal that would make it easier to make these effective interventions immediately available to everyone who needs them, when they need them.

It would also make it much easier for busy health professionals to provide the necessary advice to patients regarding self management of their condition if it worsens; easier because the inhaled treatment advice for attacks would be essentially the same for all patients with asthma and the same for all patients with COPD. How to use the emergency treatment packs would be suitable for group teaching both for patients and for health professionals.

This would represent a substantial change in routine practice by all of us who care for these patients. But we think it has the potential to deliver better results from the initial self-management of exacerbations of asthma and COPD and potentially to save lives.

We are extremely interested in hearing your views on the article – either via a letter to Pulse (pulsefeedback@cogora.com), emailing me (duncan.keeley@nhs.net), or writing to Lancet Respiratory Medicine.

Dr Duncan Keeley is a GP in Thame, Oxfordshire. He is also policy lead of the Primary Care Respiratory Society, but is writing in a personal capacity

Reference: