Revealed: How patients referred to mental health services end up back with their GP

The success of the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) scheme is world famous. Last year, the New York Times called it the ‘world’s most ambitious effort to treat depression, anxiety and other common mental illnesses’ – a claim repeated by former health secretary Jeremy Hunt and NHS England.

Since its introduction 10 years ago, it has become the jewel in the crown of the NHS drive to create parity of esteem between mental health and physical health.

Current health secretary Matt Hancock has acknowledged that parity has yet to be achieved on World Mental Health Day last month.

‘Mental health has simply not had the same level of support – both in terms of resources, but also in terms of how we as a society talk about it – compared to physical health, and we want to change that,’ he said, as the Government appointed the first-ever minister for suicide prevention.

Yet the IAPT scheme, which started being rolled out in England in 2008 with an investment of £300m and offered a service to which GPs could refer patients, is held up as a success story.

Under the programme, patients may also self-refer, allowing them to avoid a GP consultation, with the aim of overcoming the stigma of having a mental health problem. Now more than 900,000 people access the therapy every year.

The programme is meeting its national waiting time targets, introduced in April 2015 by NHS England to ensure 75% of people start treatment within six weeks of referral, and 95% within 18 weeks.

At the same time, IAPT is meeting the national target for at least half of all patients who complete treatment to have ‘recovered’, measured according to how far someone’s condition has improved, based on a clinical scoring system.

Hidden problems

However, the reality for GPs is this may be a case of hitting the target but missing the point, with IAPT’s apparent success hiding problems with the service and with mental health provision as a whole as it struggles to keep up with demand.

Commissioners are focusing their energy on meeting targets but, once these targets are achieved, a significant proportion of patients can be left with nowhere to go but back to their GPs.

A Pulse analysis of NHS Digital data has shown that 30% of people referred to IAPT never begin treatment, with 42% of those who do start the programme only ever completing one session. And of those who do go beyond one session, more than 50% are now having to wait longer than a month between their first and second appointments, which is contrary to NICE guidelines.

NHS Digital’s data on why referrals end do not include a specific breakdown showing the reasons why treatment stops, so these figures are likely to be attributable at least in part to patients choosing to drop out or being referred to another service deemed more appropriate than IAPT.

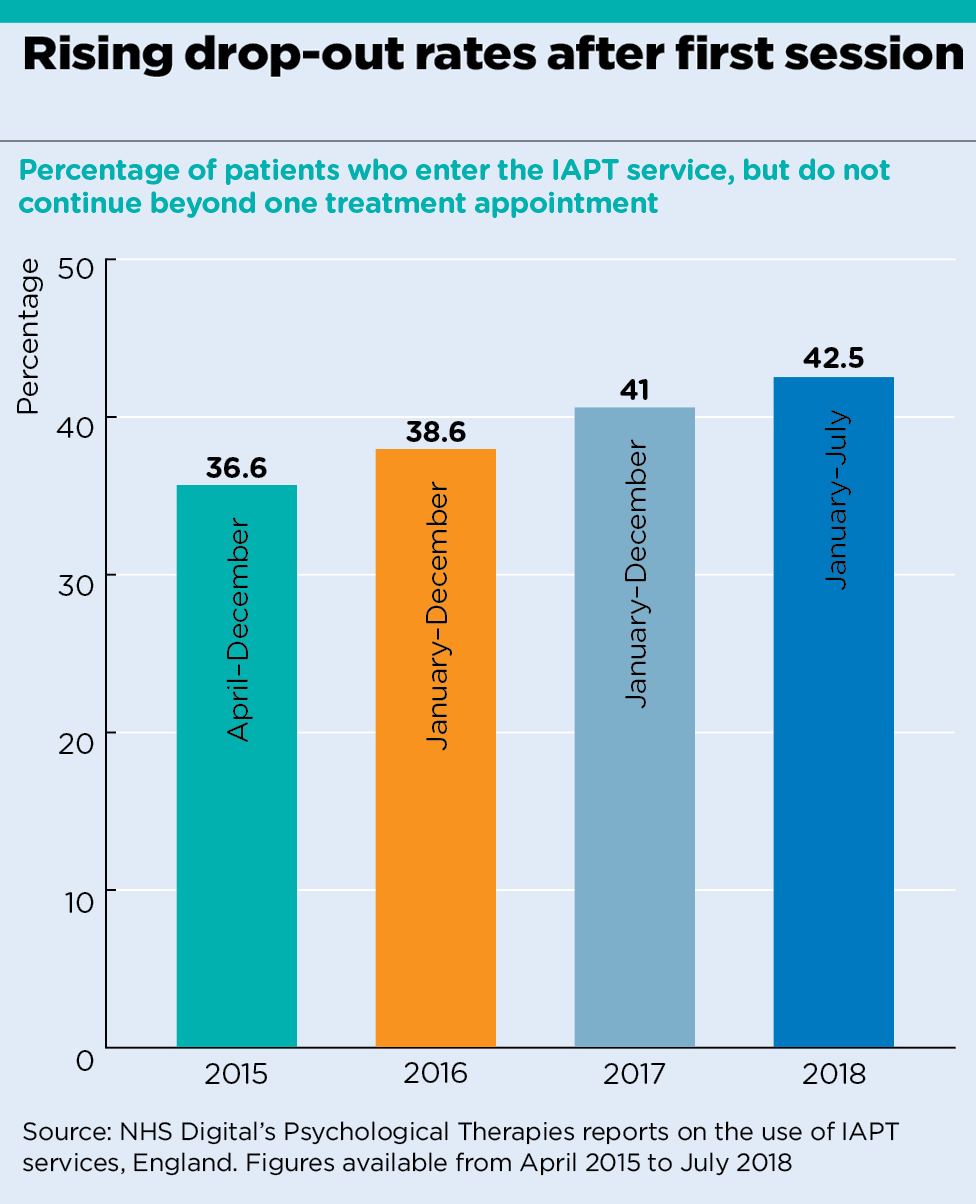

However, Pulse’s analysis of the data does show that, since the targets were introduced in 2015, there has been an increase in the proportion of IAPT participants who fail to complete more than a single treatment session, rising from 36% in 2015 to 42% in 2018 (see chart below).

analysis graph 1

Some say the introduction of the targets could be a factor in this increase, as they provide an incentive for commissioners to rush through the initial session after referral.

Some of the dropouts occur through the use of group consultations by CCGs – which helps them meet the targets.

Dr Dominique Thompson, a specialist student health GP, says these consultations work for some patients, but often put others off.

She says: ‘Theoretically, if they are offered a group, that might in itself be a barrier, even if the care would be equally good if they gave it a chance.’

The targets also mean there is little incentive to provide patients with a timely follow-up appointment.

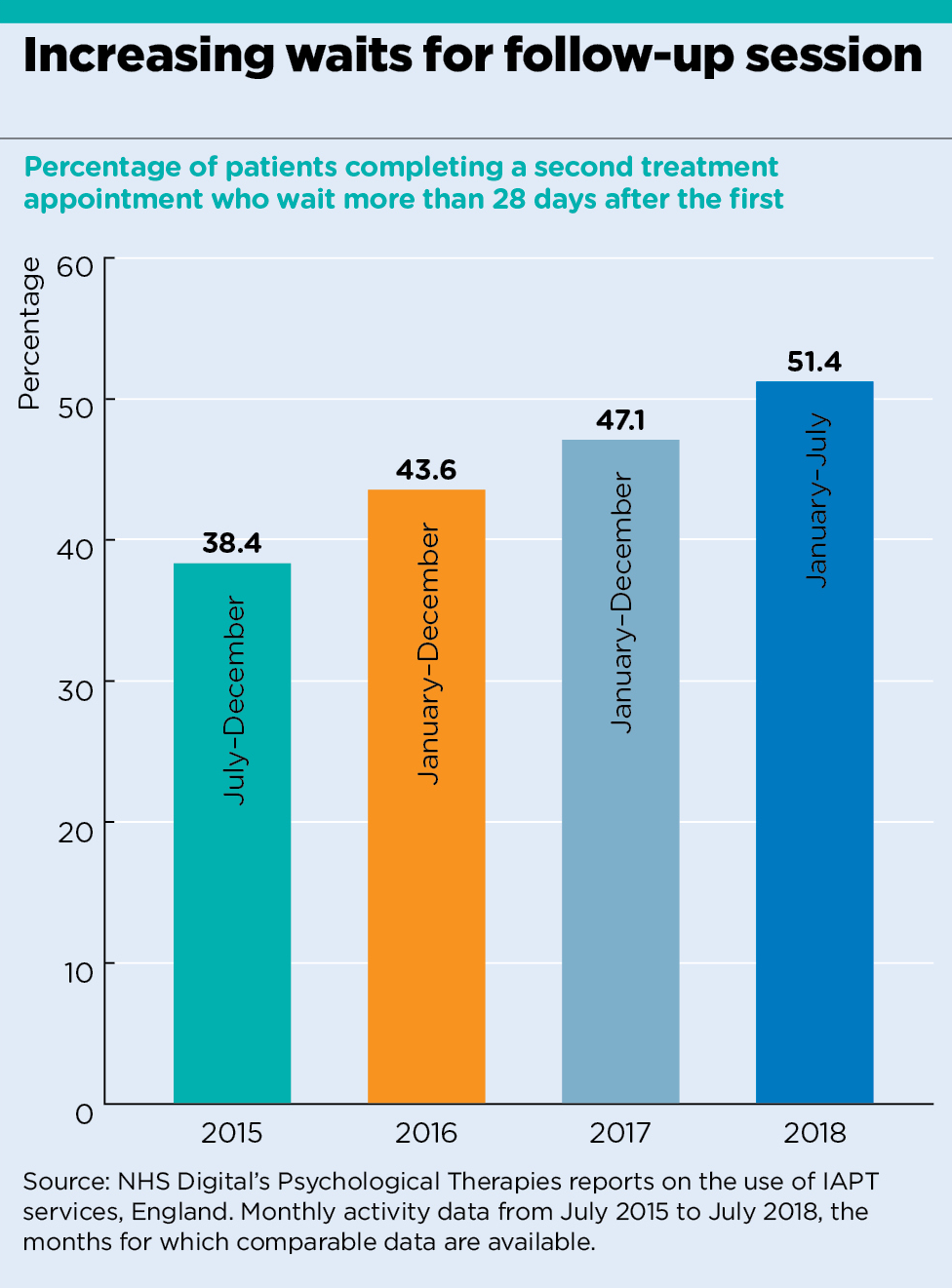

This appears to have caused an increase in the proportion of patients waiting more than a month for their second treatment. In 2015, 38% waited longer than a month; by 2018, this had risen to 51%.

analysis graph 2

West Kent LMC representative and Maidstone GP Dr Zishan Syed says the pressure to meet initial waiting time targets ‘seems to have a knock-on impact on waiting times for the following appointments’.

‘What we are seeing is a tickbox approach used to give the impression of progress when in fact nothing worthwhile is achieved for patients.

‘By the time a patient is seen at the second appointment, any value from the first will have been lost. These are very worrying times.’

Mental health charity Mind is also concerned about the detrimental impact these delays are having on patients.

Mind senior policy and campaigns officer Emily Waller says: ‘Many people tell us waiting a long time for a second appointment makes them more likely to disengage from therapy and for their mental health to get worse.

‘When people don’t get the help and support they need, they are likely to need more intensive and expensive support further down the line.’

Lengthy delays between first and second treatments run counter to NICE’s guidance on the use of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for common mental health problems, which states: ‘For people with depression it should be in the range of 16 to 20 sessions over three to four months’; for people with generalised anxiety disorder ‘it should usually consist of 12 to 15 weekly sessions’.

There is an inevitable effect on GPs’ patient care. Liverpool LMC secretary and a GP in the city Dr Rob Barnett says: ‘There is no doubt the services are working to meet the targets set, but like all NHS targets, they are meaningless when it comes to individual patients.

‘The experience patients tell us about is clearly that things are not where they should be – where patients should be having regular counselling or CBT delivered within a reasonable period.’

Stringent criteria

The first appointment target is not the only one having adverse effects on patients. Experts say the target of achieving ‘recovery’ for 50% of patients going through a full IAPT course may be inducing some regions to introduce more stringent criteria for patients to access the treatment in the first place.

Professor Linda Gask, emerita professor of primary care psychiatry at the University of Manchester, says the targets lead to ‘services trying to look good in the numbers… they use strict exclusion and inclusion criteria to restrict who they take on.’

The exclusion criteria include ‘people they deem not to be motivated’. As a result, ‘they get better outcomes, because they don’t have as many DNAs’, she says.

Professor Gask warns this leaves GPs with patients they are unable to get into treatment.

‘I think these criteria play a big part in who gets treated, and GPs might say that in some areas they are applied quite restrictively. It all depends on what services individual CCGs decide to invest in. This means there is a lot of variation in who gets taken on across different areas,’ she says.

In Liverpool, Dr Barnett says services last year ‘couldn’t have been much worse’ and ‘GPs did not bother to refer patients [to IAPT] because nothing would happen’.

There have been improvements to the city’s service but it is still not working in patients’ best interests. He says: ‘The service looks at ways of not accepting patients. In my area, if you have a patient who is under another service, for example addiction or drug misuse services, they will not be accepted by IAPT.

‘Patients can have two ongoing issues, which are not necessarily related. To say they should not have a particular service because they are attending someone else, I think is doing patients a disservice.’

A spokesperson for Mersey Care NHS Foundation Trust, which has run Liverpool’s IAPT programme since 2015, says it excludes patients who are under another service ‘to safeguard consistency of service for the good of the patient’.

They say the trust has reduced waiting times since taking over the service and that it is ‘continually looking at ways to improve how people access our services’.

These problems come on top of other issues within mental health services. In September, Dr Jon Goldin, vice-chair of the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Faculty, spoke out about CAMHS being so overstretched that the service ‘was not meeting the need’, meaning it was ‘not fit for purpose’.

Shortly afterwards, a report by the National Audit Office found children and young people will still face ‘significant unmet need’ in accessing mental health services even if the Government hits its target for 35% of young people with diagnosable conditions to be accessing them by 2020/21.

These problems mean it is GPs who are left supporting patients with mental health problems, often beyond their levels of expertise. A survey of GPs by Mind earlier this year showed 40% of all consultations now see patients raising a mental health problem.

Dr Syed says the lack of timely access to overstretched mental health services places extra responsibility on GPs.

‘In some cases patients are effectively being discharged with no option but to be seen by the GP, despite extremely high level needs for which we’re not resourced.

‘It often feels that the risk associated with mental health care is conveniently being dumped onto GPs to manage.’

With few mental health services to refer to, antidepressants can sometimes be the only option left to GPs.

BMA GP Committee chair Dr Richard Vautrey warns that ‘commissioners need to be vigilant that people don’t fall through the cracks between different services when their referral isn’t accepted or patients don’t complete treatment.’

For Dr Vautrey, having therapists linked to practices will make the difference: ‘The number of patients needing help with mental health problems is increasing so we need greater investment in community-based mental health services.’

NHS England says it is continuing to expand the primary care therapist workforce. A spokesperson stresses the success of the programme so far: ‘IAPT in the past year alone has had over one million people referred for care, met every performance target consistently and has helped hundreds of thousands of people manage their mental health.’

But until this increase in the workforce is delivered, IAPT’s successes risk being overshadowed by problems – and GPs will continue to pick up the slack.

Mental health therapists in GP practices

In April 2016, NHS England’s GP Forward View pledged to recruit 3,000 extra fully funded practice-based mental health therapists by 2020/2021 to help expand IAPT. NHS England said the additional staff were expected to result in an average of a full-time therapist for every two to three ‘typical-sized’ practices.

Last year NHS England was forced to address concerns that staff may not be fully integrated in primary care teams, after it was revealed the vast majority of the new therapists will be employed by IAPT providers rather than practices.

Managers insisted they had not ‘broken any promises’ as the therapists will be based in practice buildings or within primary care teams ‘depending on what makes sense for local patients and services.’

In August, NHS England said that since the GP Forward View’s launch in 2016, 800 extra mental health workers had been recruited to IAPT, as of December 2017. Earlier in the summer it said recruitment was ‘in line with the GP Forward View commitment’ and there was ‘progress in many areas of the country’.

Pulse July survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens