The new NOGG guidelines for osteoporosis

The National Osteoporosis Guideline Group (NOGG) guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis were first published in 2009 and updated in 2013. The new fully revised version, published in 2017, has achieved accreditation from NICE and has been endorsed by the RCGP.

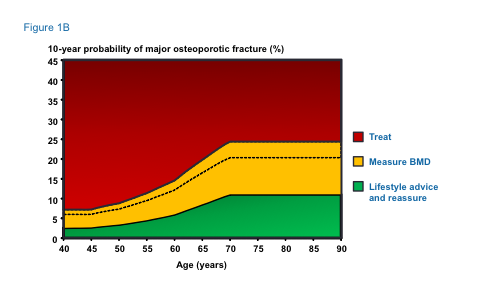

The main areas updated are a slight change to the intervention thresholds (see Fig 1b) as there had been criticism that older people were disadvantaged.

Summary of main recommendations

Assessment of fracture risk

Fracture probability should be assessed in postmenopausal women, and men age 50 years or more, who have risk factors for fracture, using FRAX. In individuals at intermediate risk, bone mineral density (BMD) measurement should be performed using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) and fracture probability re-estimated using FRAX.

Vertebral fracture assessment should be considered in postmenopausal women and men aged over 50 years if there is a history of ≥4cm height loss, kyphosis, recent or current long-term oral glucocorticoid therapy or a BMD T-score ≤ -2.5.

Many GPs use the QFracture risk assessment tool rather than FRAX as it is integrated into the EMIS computer software. There are pros and cons of each tool and NICE advises GPs to perform a fracture risk assessment using either tool. The SIGN guideline for managing osteoporosis3 prefers QFracture.

The advantage to using FRAX is that it links directly into the NOGG guidelines that give you advice as to treat without DXA, advise lifestyle advice or ask for bone densitometry. Since FRAX and QFracture yield different outputs (probability of fracture accounting for mortality risk in the case of FRAX and a cumulative risk of fracture in the case of QFracture), the two calculators cannot be used interchangeably. In addition, BMD cannot be incorporated into QFracture estimations. Finally, the NOGG intervention thresholds are based on FRAX probability and so cannot be used with fracture risk derived from QFracture or other calculators.4

One of the main weakness of either fracture risk assessment tool is they take no account of prior treatments or of dose responses for several risk factors. For example, two prior fractures carry a much higher risk than a single prior fracture and a previous vertebral fracture has double the risk than other prior fractures. There are always limitations to any algorithm that require clinical judgement to reflect and adjust treatments and advice accordingly (see table 2). For several interventions (raloxifene, strontium ranelate, teriparatide) the response to treatment is independent of FRAX whereas in others (abaloparatide, bazedoxifene, denosumab, clodronate), the response is greater in patients with the higher fracture probabilities identified on the basis of clinical risk factors alone.5

The femoral neck is the preferred site for DEXA measurement because of its higher predictive value for fracture risk.6 The spine is not a suitable site for diagnosis in older people because of the high prevalence of degenerative changes, which artifactually increase the BMD value. It is, however, the preferred site for assessing response to treatment.

| Routine | Other investigations, if indicated |

|---|---|

|

History and physical examination |

Lateral radiographs of lumbar and thoracic spine or DEXA-based lateral vertebral imaging |

|

Blood cell count, sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein. Serum calcium, albumin, creatinine, phosphate, alkaline phosphatase and liver transaminases |

Serum protein immunoelectrophoresis and urinary Bence Jones proteins |

|

Bone densitometry (DEXA) |

Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D |

|

Thyroid function tests |

Plasma parathyroid hormone |

|

Serum testosterone, sex hormone binding globulin, follicle stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone (in men) |

|

|

Serum prolactin |

|

|

24 hour urinary free cortisol/overnight dexamethasone suppression test |

|

|

Endomysial and/or tissue transglutaminase antibodies |

|

|

Isotope bone scan |

|

|

Markers of bone turnover |

|

|

Other investigations, for example, bone biopsy and genetic testing for osteogenesis imperfecta, are largely restricted to specialist centres. |

Table 1 – Investigations proposed in the investigation of osteoporosis

Risk factors for osteoporosis/ fractures not presently accommodated in FRAX

- Thoracic kyphosis

- Height loss (>4cm)

- Type 2 diabetes

- Falls

- Inflammatory disease such as ankylosing spondylitis, other inflammatory arthritides, connective tissue diseases

- Endocrine disease such as hyperthyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, Cushing’s disease

- Haematological disorders or malignancy

- Muscle disease such as myositis, myopathies and dystrophies

- Respiratory disease such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- HIV infection

- Neurological or psychiatric disease such as Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, stroke, depression, dementia

- Nutritional deficiencies such as calcium, vitamin D, magnesium, protein. NB. vitamin D deficiency may contribute to fracture risk through undermineralisation of bone (osteomalacia) rather than osteoporosis

- Medications:

- Some immunosuppressants such as calmodulin/calcineurine phosphatase inhibitors

- Excess thyroid hormone treatment such as levothyroxine or liothyronine. Patients with thyroid cancer with suppressed TSH are at particular risk.

- Drugs affecting gonadal hormone production such as aromatase inhibitors, androgen deprivation therapy, medroxyprogesterone acetate, gonadotrophin hormone releasing agonists

- Some diabetes drugs

- Some antipsychotics

- Some anticonvulsants

- Proton pump inhibitors

Lifestyle and dietary measures

- A daily calcium intake of between 700 and 1200mg should be advised, if possible achieved through dietary intake, with use of supplements if necessary.

- In postmenopausal women and older men (≥50 years) at increased risk of fracture a daily dose of 800IU cholecalciferol should be advised.

- In postmenopausal women and older men receiving bone protective therapy for osteoporosis, calcium supplementation should be given if the dietary intake is below 700mg/day, and vitamin D supplementation considered in those at risk of or with evidence of vitamin D insufficiency.

- Regular weight-bearing exercise should be advised, tailored according to the needs and abilities of the individual patient, as well as quitting smoking and reducing alcohol to ≤2 units/day.

- Falls history should be obtained in individuals at increased risk of fracture and further assessment and appropriate measures undertaken in those at risk.

The Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) has recently recommended a reference nutrient intake (RNI) of 400IU daily for adults of all ages (SACN 2016). This is a general public health measure and not specifically aimed at people with osteoporosis and fragility fracture. In the high risk group a protective effect of vitamin D on fractures was seen at a daily dose of 800IU.8

Pharmacological intervention in postmenopausal women

| Intervention | Vertebral fracture | Non-vertebral fracture | Hip fracture |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Alendronate |

A |

A |

A |

|

Ibandronate |

A |

A* |

NAE |

|

Risedronate |

A |

A |

A |

|

Zoledronic acid |

A |

A |

A |

|

Calcitriol |

A |

NAE |

NAE |

|

Denosumab |

A |

A |

A |

|

HRT |

A |

A |

A |

|

Raloxifene |

A |

NAE |

NAE |

|

Teriparatide |

A |

A |

NAE |

A: grade A recommendation. NAE: not adequately evaluated

* in subsets of patients only (post-hoc analysis) HRT: hormone replacement therapy

Table 2 – Antifracture efficacy of approved treatments for postmenopausal women with osteoporosis when given with calcium and vitamin D

Alendronate or risedronate are first line treatments in the majority of cases. In women who are intolerant of oral bisphosphonates or in whom they are contraindicated (often upper GI problems), intravenous bisphosphonates or denosumab provide the most appropriate alternatives, with raloxifene, strontium ranelate or hormone replacement therapy as additional options. All bisphosphonates are contra-indicated with severe renal impairment (GFR ≤ 35ml/min for alendronate and zoledronic acid and ≤30ml/min for other bisphosphonates). The high cost of teriparatide restricts its use to those at very high risk, particularly for vertebral fractures.

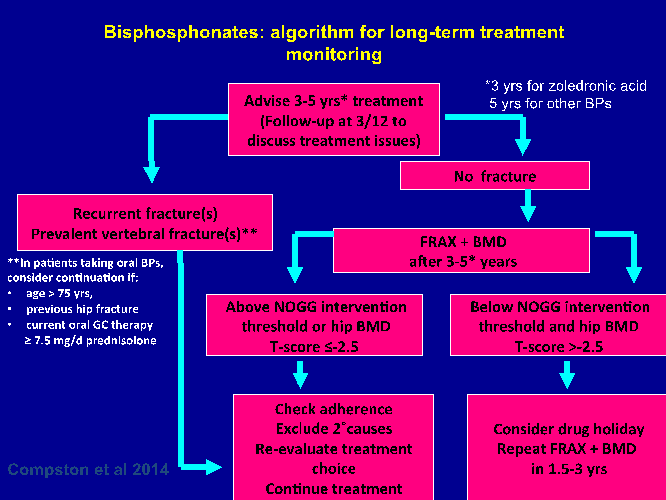

Treatment review should be performed after three years of zoledronic acid therapy and five years of oral bisphosphonate treatment (see Fig 1a). Continuation of bisphosphonate treatment beyond 3-5 years can generally be recommended in individuals at high risk, i.e. age ≥75 years, those with a history of hip or vertebral fracture, those who sustain a fracture while on treatment, and those taking oral glucocorticoids.

Figure 1a: Bisphosphonate algorithm for long-term treatment monitoring9

If treatment is discontinued, fracture risk should be reassessed after a new fracture, regardless of when this occurs. If no new fracture occurs, assessment of fracture risk should be performed again after 18 months to three years.

There is no evidence to guide decisions beyond 10 years of treatment and management options in such patients should be considered on an individual basis. Following cessation of denosumab therapy there is rapid bone loss, so at present it is best to stay on denosumab, but in patients who stop, switching to an alternative such as a bisphosphonate should be considered.

Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis

- Women and men age ≥70 years and those with a previous fragility fracture or taking high doses of glucocorticoids (≥7.5mg/day prednisolone) should be considered for bone protective therapy.

- In other individuals, fracture probability should be estimated using FRAX with adjustment for glucocorticoid dose.

- Bone protective treatment should be started at the onset of glucocorticoid therapy in individuals at high risk of fracture.

- Alendronate and risedronate are first line treatment options. Where these are contraindicated or not tolerated, zoledronic acid or teriparatide are alternative options.

- Bone protective therapy may be appropriate in some premenopausal women and younger men, particularly in individuals with a previous history of fracture or receiving high doses of glucocorticoids.

Osteoporosis in men

- Secondary causes of osteoporosis are commonly found amongst men, so this population requires thorough investigation. Alendronate and risedronate are first line treatments in men. Where these are contraindicated or not tolerated, zoledronic acid or denosumab provide the most appropriate alternatives, with strontium ranelate or teriparatide as additional options.

- All men starting on androgen deprivation therapy should have their fracture risk assessed, and treated appropriately.10

Intervention thresholds for pharmacological intervention

The thresholds recommended for decision-making are based on probabilities of major osteoporotic and hip fracture derived from FRAX and can be similarly applied to men and women.

Women with a prior fragility fracture can be considered for treatment without the need for further assessment, although BMD measurement may be appropriate, particularly in younger postmenopausal women. Age-dependent intervention thresholds up to 70 years and fixed thresholds thereafter provide clinically appropriate and equitable access to treatment (see Figure 1b).

Systems of care

Coordinator-based Fracture Liaison Services (FLS) should be used to systematically identify men and women with fragility fracture. FLS provide fully coordinated, intensive models of care for secondary fracture prevention. They are cost-effective and are more effective in improving patient outcomes than approaches involving GP or patient alerts or patient education only. The ideal approach is a service in which identification, assessment and osteoporosis treatment are all conducted within an integrated electronic health care network, overseen by a coordinator and utilizing a dedicated database measuring performance. Collaboration between geriatricians, orthopaedic surgeons, and primary care practitioners and between the medical and non-medical disciplines concerned should be encouraged wherever possible.

Dr Sally Hope is an associate specialist in osteoporosis at Oxford University Hospitals

References

- Svedbom A, Hernlund E, Ivergård M et al and the EU review panel of the IOF. Osteoporosis in the European Union: A compendium of country-specific reports. Arch Osteoporos 2013; 8:137. DOI 10.1007/s11657-013-0137-0.

- van Staa TP, Dennison EM, Leufkens HG, Cooper C. Epidemiology of fractures in England and Wales. Bone 2001; 29:517-22.

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (2015) Management of osteoporosis and the prevention of fragility fractures. Edinburgh: SIGN; 2015. (SIGN publication no. 142). http://www.sign.ac.uk.

- Kanis JA, Compston J, Cooper C et al. SIGN Guidelines for Scotland: BMD Versus FRAX Versus QFracture. Calcif Tissue Int 2016;98:417-25.

- Kanis JA, McCloskey E, Johansson H, Oden A, Leslie WD. FRAX® with and without BMD. Calcif Tissue Int 2012;90: 1-13.

- Kanis JA, Gluer CC. An update on the diagnosis and assessment of osteoporosis with densitometry. Committee of Scientific Advisors, International Osteoporosis Foundation. Osteoporos Int 2000;11:192-202.

- McCloskey E, Kanis JA, Johansson H et al. FRAX-based assessment and intervention thresholds – an exploration of thresholds in women aged 50 years and older in the UK. Osteoporos Int 2015;26:2091-9.

- Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Willett WC, Wong JB et al. Prevention of nonvertebral fractures with oral vitamin D and dose dependency: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 2009a;169:551-61.

- NOGG 2017

- https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg175/chapter/1Recommendations#men-having- hormone-therapy-2

Pulse July survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens

Visit Pulse Reference for details on 140 symptoms, including easily searchable symptoms and categories, offering you a free platform to check symptoms and receive potential diagnoses during consultations.