After Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, motor neurone disease (MND) is the third most common adult-onset neurodegenerative condition in the UK, although GPs will probably only see a handful of cases during their careers. Progressive degeneration of the upper motor neurones within the cortex of the brain and the lower motor neurones in the brainstem and spinal cord result in the core features of progressive skeletal muscle wasting and weakness.1 Although the drug riluzole has been shown to slow down the progression of the illness,2 MND is currently a life-limiting illness with no cure, with death ultimately occurring usually from respiratory failure.3

Incidence and prevalence

The precise figures for the incidence and prevalence of MND are not certain, but approximately 4500 people are living with MND in the UK at any one time.4 This equates to an incidence of around 1-2 per 100,000 per year, with a prevalence of around seven per 100,000.1

MND can affect any age, but the incidence is highest in those aged between 55-79 years. Onset below the age of 40 is uncommon.1 The male to female ratio is 3:2, although this does vary with age and subtype.1,4

Aetiology

Most people who develop MND have no apparent family history of the disease. In these ‘sporadic’ cases, it is likely that the disease develops due to a combination of genetic susceptibility and environmental factors.5 Approximately 5-10% of all MND cases are familial.1,5

More from this series: How to spot zebras – Behçet’s disease

Subtypes of MND

The term MND in the UK and Australia is an overarching term used to describe all subtypes of the disorder. Classically there are four main subtypes, classified by whether the upper motor neurones and/or the lower motor neurones are affected. These are amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), progressive bulbar palsy (PBP), progressive muscular atrophy (PMA) and primary lateral sclerosis (PLS). Clinically, there is often considerable overlap seen between each subtype.

ALS is the most common form of MND and accounts for about 80-85% of all cases.4,7 Both upper motor neurone and lower motor neurone degeneration occurs, so mixed upper motor neurone and lower motor neurone features are seen on examination, in the same territory.1,8 Spasticity (increased limb tone), hyperreflexia (brisk tendon reflexes) and extensor plantar responses are typical of the upper motor neurone involvement. Muscle wasting, weakness, fasciculations and reduced or absent tendon reflexes are typical lower motor neurone findings. Onset can be either limb or bulbar in nature. Prognosis is two to five years from symptom onset.7

The term PBP is often used to describe a subgroup of MND patients who initially present with bulbar features, which are confined to this region for several months (occasionally years) before then involving other regions. Degeneration of both upper motor neurones and lower motor neurones occurs. Prognosis is between six months and three years from symptom onset.7

PMA is a more unusual MND subtype, which accounts for about 5-10% of people with MND and is characterised by purely lower motor neurone degeneration. The prognosis is around four years, but those presenting with single limb involvement may live 10 or more years from symptom onset.7

PLS is a rare subtype, which accounts for approximately 2% of all people with MND. This subtype affects the upper motor neurones only. This has the best prognosis of 10 years or more from symptom onset.7

Clinical Presentation

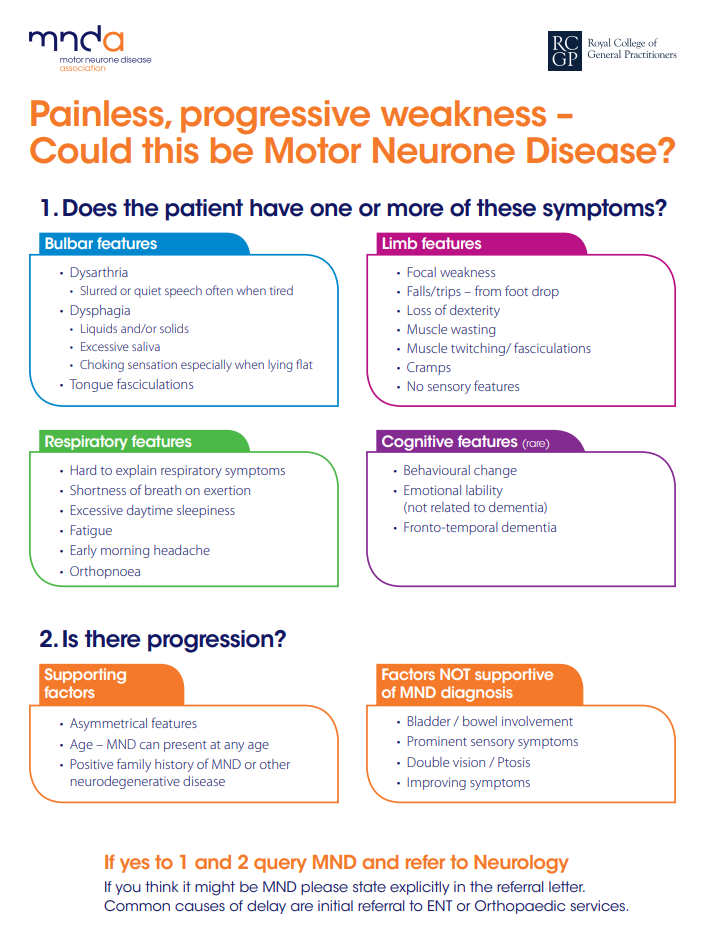

The Motor Neurone Disease Association (MNDA), in partnership with the Royal College of General Practitioners, produced the ‘Red flag tool’ to aid diagnosis, pictured below and downloadable here.9 It details the common features related to bulbar, limb and respiratory presentation, as well as those of cognitive disturbance. The tool also details supporting and non-supporting factors when a diagnosis of MND is being considered.

Source: Motor Neurone Disease Association

Initially clinical features tend to be focal and then spread to other regions, the rate and pattern of progression varying from patient to patient and the MND subtype. Limb and bulbar symptoms are easier to recognise than early respiratory symptoms, especially subtle features of nocturnal hypoventilation. Cognitive involvement, particularly executive dysfunction and behavioural changes are seen in up to 50% of patients.1 Overt frontotemporal dementia occurs in up to 5-10%.10

There are a number of MND ‘mimics’, some of which are treatable, so they are important to identify. Although not an exhaustive list, table 1 shows some of the more common conditions and relevant investigations.

| Differential diagnosis | Relevant investigations |

|---|---|

|

Multilevel spinal spondylotic pathology |

MRI |

|

Multifocal cerebrovascular disease |

Computed tomography or MRI imaging of the brain

|

|

Motor neuropathies |

Immunoglobulins and plasma electrophoresis Nerve conduction studies (NCS) |

|

Myopathies |

FBC, creatine kinase, CRP, ESR Electromyography (EMG) Muscle biopsy |

|

Myasthenia gravis |

Acetylcholine receptor antibody, MUSK antibody, EMG/NCS studies (including single fibre EMG and repetitive stimulation) |

|

Syringomyelia and syringobulbia |

MRI of brain and spine |

|

Hyperthyroidism |

TFTs |

|

Vitamin D and B12 deficiencies |

Vitamin D +/- parathyroid (PTH) and calcium levels, B12 levels |

|

Lead or mercury toxicity |

Heavy metal assays |

|

Spinal muscular atrophy |

Gene analysis |

|

Kennedy’s disease |

Gene analysis |

|

Benign cramp/fasciculation syndrome |

EMG |

|

Post-polio syndrome |

EMG |

|

Multifocal motor neuropathy with conduction block |

Anti-ganglioside antibodies NCS |

|

Hexosaminidase deficiency |

Hexosaminidase A and B assays |

Table 1. Differential diagnosis and relevant investigations

When should a GP refer for a neurological opinion?

The average delay in diagnosis is usually more than a year,11 patients often having undergone a number of potentially unnecessary investigations under the care of multiple specialties. Bulbar presentation, weight loss, poor respiratory function, older age and shorter time from first developing symptoms to the time of diagnosis are all associated with a shorter survival. Prompt, appropriate treatments and interventions all help to improve the quality of life for people with MND, so urgent referral to the right specialist for a rapid accurate diagnosis at the earliest possible stage is crucial.

Making the diagnosis

If a patient exhibits one or more features from section 1 of the red flag tool, with supportive features from section 2, and there is clinical evidence for progression, urgent referral to a neurologist (preferably one with an interest and expertise in MND) is recommended.

The diagnosis of MND is based on clinical findings as currently there is no one disease-specific test. EMG, NCS and imaging are helpful to rule out MND mimics. Although I would not expect a GP to make the diagnosis, helpful information in the referral letter would include a relevant history, as well as neurological examination findings. Some of the basic blood tests listed in table 1 would be a useful addition.

How can GPs help when MND is suspected or confirmed?

Despite the many advances in understanding the pathogenesis of MND in recent years, many professionals are still pessimistic about the treatment they feel they are able to offer patients and their ability to convey hope, especially knowing that the prognosis is generally poor.

However GPs and primary care teams, in collaboration with specialist MND multidisciplinary teams and palliative care services, can make a great difference to the quality of life of people living with MND.

The MNDA’s ‘Motor neurone disease: A Guide for GP’s and Primary Care Teams’7 is a comprehensive overview of all aspects of MND, including how a patient and their carers can be supported throughout the illness by their GP and suggested responsibilities when MND is suspected or confirmed. Specifically, it advises:

- To use the red flag tool to recognise early signs, to ensure referral on to neurology in a timely manner.

- To assess the physical, social, emotional and spiritual needs at each contact, with referral on to appropriate teams as necessary.

- To monitor symptoms, including signs of early respiratory involvement, triggering referral on to a specialist respiratory team as needed.

- To monitor cognitive change, as this has potential implications for decision making and future management.

- To provide support and information throughout the course of the illness – this may include completing a DS1500 form to support a benefit application, or advising on the need to inform the DVLA of the diagnosis.

- To prescribe repeat prescriptions for riluzole, as well as carry out blood monitoring tests, as agreed in a shared care protocol.

- To include the patient on the palliative care register where these exist

- In collaboration with neurology consultant and palliative care, to initiate appropriate management and treatment, including anticipatory symptomatic intervention.

- To help with advanced care planning, helping the patient talk through management options, including end of life decisions and advance decisions to refuse treatment, as early as possible

Dr Helen Nightingale is a specialist registrar in neurology at the James Cook University Hospital. Dr Janine Evans is a consultant neurologist at the James Cook University Hospital and the director of the Middlesbrough MNDA Care Centre.

References

- Baumer D,Talbot K and Turner MR. Advances in motor neurone disease. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2014;107 (1):14-21

- Miller RG, Mitchell JD, Moore DH. Riluzole for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)/motor neuron disease (MND). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD001447. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001447.pub3

- Corcia P, Pradat PF, Salachas F et al. Causes of death in a post-mortem series of ALS patients. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2008;9(1):59-62.

- Chio et al.Global Epidemiology of Amyotrophic lLateral Sclerosis; A systemic review of the published literature. Neuroepidemiology. 2013; 41:118-130.

- Zarei S, Carr K, Reiley L, et al. A comprehensive review of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Surgical Neurology International. 2015;6:171. doi:10.4103/2152-7806.169561.

- Byrne S, Walsh C, Lynch C. et. al.Rate of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011 Jun;82(6):623-7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.224501. Epub 2010 Nov 3.

- Available at: https://dbsy278t81889.cloudfront.net/app/uploads/2012/04/19135714/px016-motor-neurone-disease-a-guide-for-gps-and-primary-care-teams.pdf [Accessed 20/03/2018]

- Talbot K Motor neuron disease Practical Neurology 2009;9:303-309.

- Available at: https://www.mndassociation.org/get-involved/campaigning/take-action/early-diagnosis-of-mnd-raise-awareness-with-your-gp/ [Accessed 07/03/2018]

- Phukan J, Elamin M, Bede P, et al. The syndrome of cognitive impairment in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a population-based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2012;83:102–8.

- Mitchell JD, Callagher P, Gardham J, et al. Timelines in the diagnostic evaluation of people with suspected amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)/motor neuron disease (MND)—a 20-year review: Can we do better? Amyotroph Lateral Scler 2010;11:537–41

Pulse October survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens