Covid-19: atypical presentations, complications and long-term effects

It has become clear in the four months since Covid-19 hit the UK that it presents in many atypical ways, some of which have potential to cause serious illness without any respiratory symptoms. With the easing of lockdown it’s important that we are alert to all possible presentations, and understand the short-term complications and long-term effects.

Atypical presentations and short-term complications

Anosmia

The best-known ‘atypical’ symptom is anosmia. On 1 April, Pulse published an article alerting GPs to research that highlighted anosmia as a possible symptom of Covid-19. This followed an alert from ENT UK, which pointed out that in South Korea – where testing was much more common than in the UK – 30% of patients with Covid-19 had anosmia as their main significant symptom. The alert also said that ENT surgeons were seeing patients who had anosmia but no other symptoms, and suggested these people should be asked to self-isolate for seven days, in a bid to reduce transmission.

It took seven weeks for anosmia to be added to the official list of symptoms that should prompt self-isolation. There is a significant minority of patients with only anosmia as a symptom, and the hayfever season makes this more complicated. The evidence suggests smell and taste usually recover within two to four weeks, but anecdotally some patients are reporting anosmia for much longer in the absence of other symptoms.

Effect on children

It has been reassuring to know that children who are otherwise healthy tend to have minor symptoms if they catch coronavirus. Deaths in children were so uncommon that when a 13-year-old boy died of Covid-19 in March it made the national news but this seemed to be an isolated event, which we could place in the context of the 12 or so children who die in the UK every year of flu.

Things became less clear in April with an alert from the North Central London CCG, which highlighted a paediatric multisystem inflammatory state, requiring admission to intensive care. Some, but not all, of these patients had been formally diagnosed with coronavirus. Public Health England rapidly instituted a surveillance scheme to follow up all children with coronavirus. The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health has published a case definition, which shows this syndrome has some features in common with Kawasaki disease, although it has now been confirmed as a new clinical entity. Key things for GPs to know are that affected children are likely to be older than those with Kawasaki disease (average age of nine compared with four) and that diarrhoea and abdominal pain are prominent symptoms. BAME children are more at risk than Caucasians.

The case definition states that a child should have fever or features of inflammation, with single- or multi-organ involvement, and that other bacterial causes must have been excluded. The diagnosis cannot therefore be made in primary care (as we would not have access to all the investigations that can fully exclude other bacterial causes), but the document also contains a list of symptoms, including gastrointestinal disturbances, which should prompt us to consider this as a possibility – these are listed in the box below.

Such symptoms are common in primary care and our paediatric colleagues would not thank us for sending them every patient with diarrhoea or conjunctivitis, and the reduction in face-to-face consultations hampers the all-important initial look – although video consultations are better than phone triage for this.

With this presentation in mind it is important that we are aware of non-respiratory symptoms that might be caused by Covid-19, and we should ask questions about the child’s general state. Are they eating and drinking, do they have wet nappies, are they playing and alert or drowsy and quiet? We should have a low threshold for seeing them via video if there are concerns. If worries persist after doing so, the child should probably be sent to see paediatrics on the same day. The threshold for concern should be lower for younger children and in particular babies.

Letting the parents know to ring back if the child becomes unwell is important, as is documenting this advice; Covid-19 and the new ways we work could be a fertile ground for litigation in the future, so always document your safety-netting advice.

Symptoms in a child that may indicate a multisystem inflammatory reaction to the coronavirus

• Persistent fever >38.5°C

• Abdominal pain, diarrhoea or vomiting

• Confusion or syncope

• Conjunctivitis

• Cough, sore throat or other respiratory symptoms

• Headache

• Lymphadenopathy or other swelling in the neck, hands or feet

• Rash

• Mucous membrane changes – drying or peeling

Vascular effects

It has also become clear that Covid-19 is a thrombogenic condition that can also cause vasoconstriction. The intriguing condition of ‘Covid toes’ has surfaced in the past few weeks. This presents with painful purple or red lesions on the toes, mimicking pernio (colloquially known as chilblains), caused by localised vasoconstriction. Unlike chilblains, this is not associated with particularly cold or damp weather. Anecdotal evidence and case studies suggest that many patients who have only this symptom will recover with no treatment, although there have been small case studies of patients who presented with ‘Covid toes’ who progressed to disseminated intravascular coagulation and, in some cases, death.

We are in a difficult position in the UK as ‘Covid toes’ is not officially on the list of symptoms that should prompt self-isolation. However, as the authorities were so slow to add anosmia to this list, it would seem sensible to be on the lookout for this presentation and to advise patients that although this isn’t officially a Covid symptom, it might be sensible to self-isolate for seven days. There are no official treatment guidelines but anecdotally topical steroid cream is being used with good effect.

We should also all be aware of the wider issues with Covid-19 and coagulopathies, in particular for patients who already have a hyper-coagulable state, for example due to pregnancy.

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists has advised that all pregnant women admitted with suspected or proven Covid-19 should be anticoagulated (unless they are within 12 hours of likely delivery).

In primary care we might want to be even more alert than usual to the risk of a pulmonary embolism in women who are pregnant or postpartum and have suspected Covid-19. We may start to see more women being prescribed heparin during pregnancy or the postnatal period.

Other atypical presentations

Covid-19 is clearly a chameleon of a virus that presents in many ways, and the less-common presentations include neurological symptoms, such as dizziness, ataxia, stroke and impaired consciousness.

In primary care we should continue to approach each patient with an open mind, see the patient in the safest way possible and make the key assessment as to whether they can safely stay at home or need admission to hospital.

It is also important to advise adults to report any sudden deterioration in their respiratory function, particularly shortness of breath on minimal exertion. A relatively well-known phenomenon is the day-10 cytokine storm, whereby a patient who seemed to be recovering becomes acutely unwell and develops acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or multi-organ failure requiring critical care.

Finally, it is worth being aware that GI symptoms such as diarrhoea have been documented in adults with Covid-19. Some evidence shows that those who present with only GI symptoms (and no respiratory symptoms) may have a more severe course to their disease and be at greater risk of liver injury.

Diarrhoea is clearly a common symptom, so it probably isn’t appropriate to assume every person with diarrhoea has Covid-19; again this comes down to our clinical assessment about whether the patient is systemically unwell and if they need same-day hospital review.

Long-term effects

As time goes on we will be seeing more patients who have recovered from Covid-19, as well as many who have ongoing, possibly lifelong complications of the infection. We clearly cannot yet have any proper long-term follow-up data, but there are some trends becoming apparent that are important for us in primary care.

Cardiac complications

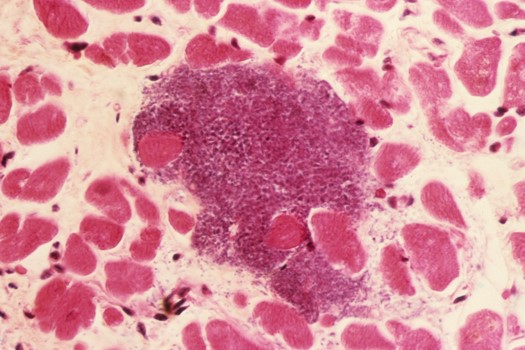

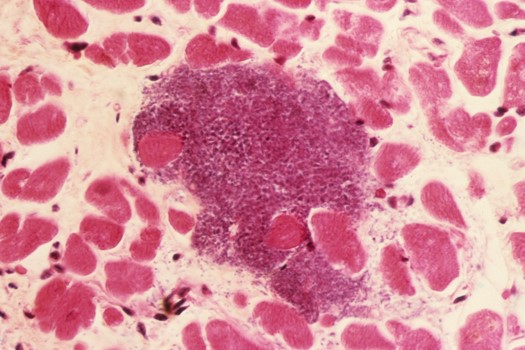

c0235466 spl infective myocarditis 525x350px SUO

Possibly the most important of these trends is the risk of cardiac complications. It is clear that Covid-19 has the potential to cause acute cardiac problems, in particular myocarditis, which has also been recognised with previous coronaviruses such as the one causing Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS). Acute heart failure, myocardial infarction and dysrhythmias have also been recorded and clearly these will all be treated during an inpatient admission. Some antivirals used to treat Covid-19 may also have cardiac side-effects, which might cause a prolonged QT interval, interfere with the electrical conduction system or have interactions with drugs such as anticoagulants, statins and anti-arrhythmics.

The biological mechanism for a cardiac effect of coronavirus is that the virus binds to cells that have a receptor for it and this includes the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), which has significant effects in the cardiovascular system. The virus down-regulates the action of ACE2, which mediates myocardial inflammation. Up-regulation of inflammatory cytokines also contributes to an overall pro-inflammatory picture that can affect many organ systems including the heart.

We have proxy data showing cardiovascular complications from other respiratory illnesses. A 2015 study of more than 20,000 patients found that there was an increased risk of cardiovascular disease in the group who had been admitted for pneumonia over the control group, taking into account obvious confounders. The increased hazard ratio persisted for two years in one cohort studied and 10 years in the other.

Other long-term complications

Other possible long-term harms include muscle weakness, lung fibrosis, changes on chest X-ray and reduced exercise capacity. We must also not forget the possible psychological harm to those who have spent time in ITU as well as to the families who have been bereaved, often in very difficult circumstances.

The needs of patients who have recovered will vary. Those with reduced respiratory function may benefit from pulmonary rehabilitation, though this shouldn’t start for at least eight weeks after discharge. More guidance is expected from the British Thoracic Society. Dysphagia is common after critical care and may need input from dietetics or speech and language therapists. More detail on follow-up care is available and we do not know how much of this will be arranged by outpatients and how much by GPs.

Diabetes and obesity have been shown to be predictors of a poor prognosis from Covid-19, so this should be a call to arms for primary care to aggressively manage these risk factors, and possibly commission programmes to address lifestyle and diet change.

Covid-19 is a marathon, not a sprint. It is likely that we will be seeing new cases for some time. Primary care is then going to be dealing with the fallout for years to come, from the backlog of patients who stayed at home with health problems while lockdown was in operation, to dealing with the physical and mental health complications in those who have had Covid-19 themselves, and the fallout for their relatives.

Dr Toni Hazell is a GP in north London

Pulse July survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens