GP beware – respiratory medicine

Case 1

Mrs P, a 75-year-old current smoker, has a history of emphysema controlled by a long-acting ß2/steroid inhaler, tiotropium and prn salbutamol. Over the past year, Mrs P had required two courses of oral antibiotics and steroids for infective exacerbations of COPD. She attended the emergency surgery with increased breathlessness and wheeze, and mentioned that when she was gardening the previous afternoon, she thought she had pulled a muscle on the right side of her chest. The breathlessness had worsened over night. On examination, there was wheeze and globally reduced air entry. An exacerbation of her COPD was diagnosed and antibiotics prescribed.

Later that afternoon, Mrs P’s daughter phoned the practice. She had been to visit her mother and found her unable to speak in full sentences. An ambulance was called and Mrs P was admitted to hospital. The discharge summary documented a right-sided secondary pneumothorax, requiring intercostal drain placement.

GP’s diagnosis

Infective exacerbation of COPD.

Actual diagnosis

Right-sided pneumothorax.

Clues

• Lack of infective symptoms in history.

• History of emphysema (making bullae a possibility).

• Right-sided chest discomfort the previous afternoon.

• A precipitating event to the breathlessness.

• Sudden onset of breathlessness.

Take-home messages

• In a patient with a chronic disease it is difficult not to attribute new symptoms to the underlying condition. Although this patient has had two previous COPD exacerbations in recent months, this presentation was different from the previous and there was little to point to an infective exacerbation as there was no temperature or change in sputum.

• The patient has known emphysema (with possible bullae) and the history of a ‘pulled muscle’ the previous afternoon is likely to be consistent with the rupture of a bulla. Clinical signs of a pneumothorax may be difficult to detect in the over-inflated chest of a COPD patient, but the clinical features of reduced expansion, hyper-resonant percussion note and quiet breath sounds on the pneumothorax side should be actively sought.

• One of the main differentials in this instance is a pulmonary embolus. This should always be considered in a history of chest pain and associated shortness of breath, regardless of the underlying medical history.

Case 2

James, a 13-year-old boy, attended the duty doctor surgery with his mother. Looking through his notes, the GP saw he had ongoing difficulties with constipation, requiring intermittent laxatives since childhood. James had been off school for the past two days with a chesty cough productive of green sputum, and as his cough hadn’t improved, his mother wanted someone to ‘listen to his chest’.

Examining the chest, there were crackles at the right base. It was noted that James seemed small for his age.

A week’s course of antibiotics was prescribed.

Two months later, James was brought into the surgery again. This time he was accompanied by both his mother and younger brother. It was noted that the younger brother was significantly taller than James. While he had been well after the previous consultation, his symptoms had returned. This time, examination showed crackles at the left base. A further course of antibiotics was given with instructions to return if the symptoms failed to settle.

GP’s diagnosis

Recurrent pneumonia.

Actual diagnosis

Cystic fibrosis.

Clues

• History of constipation.

• Small for age, smaller than younger brother.

• Two episodes of pneumonia in a short period.

Take-home messages

• Although cystic fibrosis is often diagnosed in early childhood, recurrent pneumonia in childhood should be a trigger for further investigation. Of note, if there is a recurrent pneumonia in the same lobe, an obstructing lesion (such as a foreign body) should be excluded.

• The difference in height between James and his younger brother points to

a ‘failure to thrive’ in James.

• Sputum cultures are of value, especially in infections that are slow to resolve or recurrent. In this case, the presence of atypical organisms may suggest underlying respiratory disease.

• While a number of features in this patient’s history point to cystic fibrosis,

it is important to review previous information when building an underlying diagnosis. Cystic fibrosis is often diagnosed in early childhood, but can become apparent later in age depending on the genetic mutation.

Case 3

Mrs J, an 81-year-old lady with a 40-pack year smoking history and well controlled heart failure (maintained on furosemide and an ACE inhibitor), presented to her practice with increased breathlessness. She had begun to find stairs a struggle and was finding it difficult to manage her weekly shop.

On examination, her pulse was regular and there was no peripheral oedema. Her chest was clear on the left, but dull to percussion on the right, and had reduced air entry to the mid zones. The signs were felt to be consistent with a pleural effusion. Repeat ECG showed no acute changes. The GP diagnosed an exacerbation of heart failure and doubled Mrs J’s furosemide, advising her to return in two weeks for review.

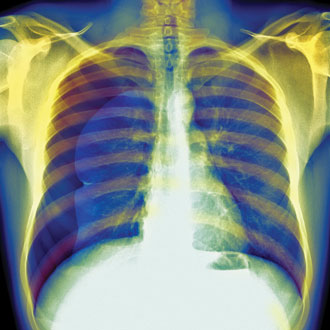

Despite the increased furosemide, Mrs J became increasingly breathless. She was unable to attend her appointment, instead calling an ambulance where she was taken to A&E. A chest X-ray was performed, showing a large right-sided effusion and a clear left lung. The pleural fluid was an exudate and a CT scan revealed a right-sided mass with pleural involvement.

GP’s diagnosis

Exacerbation of heart failure.

Actual diagnosis

Lung cancer.

Clues

• Forty pack-year smoking history.

• No peripheral oedema.

• Large unilateral effusion.

Take-home messages

• A large unilateral effusion is unlikely to be consistent with heart failure, especially in the absence of other signs/symptoms.

• There was no precipitating event to make an exacerbation of heart failure likely.

• In someone with a smoking history, consider an underlying lung cancer.

Dr Neal Navani is a consultant in thoracic medicine at University College Hospital, London

Dr Laura Succony is a senior specialist registrar and clinical fellow at University College Hospital, London

Visit Pulse Reference for details on 140 symptoms, including easily searchable symptoms and categories, offering you a free platform to check symptoms and receive potential diagnoses during consultations.