Most clinicians at some point encounter a patient who has had a cholecystectomy, but has continued to suffer from biliary type pain, or a patient who keeps suffering from bouts of pancreatic inflammation and pain for which no obvious cause can be found. These are the situations where one might think of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SOD).

SOD is a clinical syndrome in which pain, biochemical abnormalities and dilatation of the bile duct or pancreatic duct are attributed to abnormal function of the sphincter of Oddi.1

The bile duct and the pancreatic duct come together in the pancreatic head, and run together briefly before opening into the second part of the duodenum, at the ampulla of Vater. This opening is encircled by a sphincter, described by Ruggero Oddi in 1887 when he was still a student.2 This controls the flow of bile and pancreatic juice into the duodenum and prevents reflux of duodenal content into the bile duct and pancreatic duct. The sphincter is 6-10mm long and lies within the duodenal wall. A part of it encircles the common channel, and then there are separate biliary and pancreatic components.

In most other mammals, the bile duct and pancreatic duct have separate openings into the duodenum. The one other animal that has a sphincter anatomy very similar to that of humans is the Australian possum.

Types and causes

SOD may result from stenosis of the sphincter, or from dysmotility. Scarring or stenosis of the sphincter can result from the passage of stones, pancreatitis or previous endoscopic sphincterotomy. The real incidence of SOD is not known, with females affected more than men.

There are two clinical types of SOD. Biliary-type SOD is characterised by biliary pain, which may be accompanied by abnormally raised liver enzymes, dilation of the bile duct, or evidence of delayed emptying on biliary scintigraphy. It may be a cause of persistent post-cholecystectomy symptoms.

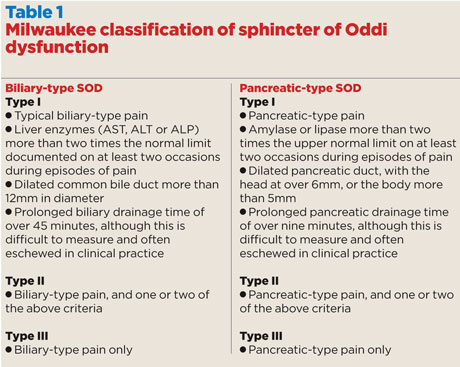

A predominance of pancreatic problems, especially recurrent episodes of acute pancreatitis, is known as pancreatic-type SOD. Each type of SOD is further divided into types I, II and III (see table 1).3 This classification helps predict the pathology and the likelihood of successful treatment. Type I is thought to result from a fixed stenosis, and responds best to therapy. An episodic dysmotility is the presumed underlying abnormality in the other types, and does not often respond as well to treatment.

Diagnosis

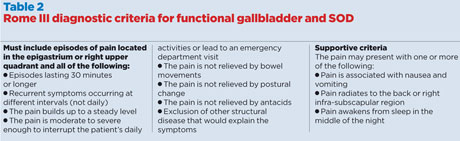

Biliary-type SOD should be considered and excluded in patients with the post-cholecystectomy syndrome. Pancreatic-type SOD should be excluded in patients with recurrent acute pancreatitis of unexplained aetiology. The role of SOD in chronic pancreatitis is unclear. A careful history is essential, and the description of pain should match the Rome III diagnostic criteria (table 2).4

CT and MRCP can demonstrate dilatation of the biliary and pancreatic ducts. MRCP with intravenous secretin injections can particularly demonstrate pancreatic duct dilatation, because of raised sphincter pressures. An endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) may achieve the same end. A quantitative cholescintigraphy (HIDA scan) may demonstrate a delayed biliary transit. The gold standard for diagnosing SOD is an ERCP with manometry of the biliary and pancreatic sphincters, although many would say that this is not essential for the diagnosis of type I SOD. ERCP with manometry is indicated if the pain is disabling, non-invasive investigations have not shown structural abnormalities, and conservative therapy has not helped. The variables customarily assessed at manometry are basal pressure and amplitude, duration, frequency, and propagation pattern of the phasic waves. A basal sphincter pressure higher than 40mmHg is the manometric criterion used to diagnose SOD.

Treatment

Endoscopic sphincterotomy is the treatment of choice for type I SOD. The question of whether dual sphincterotomies (biliary and pancreatic) should be carried out remains unanswered. There is, however, a particularly high risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis of 30% or more, although the placement of a pancreatic stent at the time of the procedure appears to reduce this risk. Such treatments are best carried out in tertiary units by expert gastroenterologists.

For patients with type II SOD, manometry should be done before considering sphincterotomy, and the results of sphincterotomy are less consistent.

Patients with type III SOD are even more difficult, with response rates to sphincterotomy ranging from 8% to 65%. Medical therapy should be tried before proceeding to manometry. PPIs, spasmolytic drugs, calcium channel blockers such as nifedipine, and psychotropic agents have all been tried with varying degrees of success. Injections of botulinum toxin, which can cause a chemical sphincterotomy for up to three months, or the placement of a pancreatic stent – usually removed after six weeks – do not provide lasting relief, but can be used to identify patients who may benefit from a sphincterotomy.

A recent study in patients with abdominal pain after cholecystectomy and suspected SOD casts doubt on the efficacy of endoscopic sphincterotomy.5 In patients undergoing ERCP with manometry, sphincterotomy versus sham did not reduce disability due to pain. Manometry results were not associated with the outcome, and no clinical subgroups appeared to benefit from sphincterotomy more than others.

In a small sub-group of patients who have experienced significant but short-lived relief with sphincterotomy or stenting, surgical transduodenal sphincteroplasty may be considered. In exceptional circumstances, where the pancreatic head is badly scarred and sphincteroplasty has failed or is unlikely to succeed, there may be grounds for surgical resection of the pancreatic head.

Key points

- Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction is a syndrome of pain, biochemical abnormality and duct dilatation caused by abnormal function of the sphincter of Oddi.

- Consider SOD in patients who continue to suffer pain post cholecystectomy or who have recurrent unexplained pancreatic pain.

- SOD may result from stenosis or dysmotility of the sphincter.

- There are two forms: biliary and pancreatic.

- Treatment is surgical and is best carried out in tertiary centres.

Mr Satya Bhattacharya is a consultant hepato-pancreato-biliary surgeon at Barts Health NHS Trust and The London Clinic

References

1 Toouli J. What is sphincter of Oddi dysfunction? Gut 1989;30:753-61

2 Oddi R. D’une disposition a sphincter speciale de l’ouverture du canal cholidoque. Arch Ital Biol 1887;8:317-22

3 Hogan WJ, Geenen JE. Biliary dyskinesia. Endoscopy 1988;20 Suppl 1:179-183

4 Behar J, Corazziari E, Guelrud M et al. Functional gallbladder and sphincter of Oddi disorders. Gastroenterology 2006;130:1498–509

5 Cotton PB, Durkalski V, Romagnuolo J et al. Effect of endoscopic sphincterotomy for suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction on pain-related disability following cholecystectomy. JAMA 2014;311:2101-9

Pulse October survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens