Case

A two-year-old girl of African ethnicity is brought to the GP by her mother because family members have noticed a swelling of the child’s wrists. Further investigation confirms age-appropriate developmental progress, apart from a delayed onset of independent walking, having started at 22 months. Dietary history suggests she was exclusively breastfed until she was four months old, and no multivitamins were taken by the mother during pregnancy or breastfeeding. The child mostly stayed indoors with her mother in a block of flats in a busy area of the town.

On examination, the child’s height and weight fall between the 0.4th and 9th centiles. Systems examination findings are normal. The wrists and ankles appear swollen but are not painful, and a bowing of the legs is evident. The abdomen appears protuberant because of low muscle tone.

Investigations confirm low serum phosphate, normal calcium and elevated alkaline phosphatase levels; 25-hydroxy vitamin D level is below 15nmol/l, and serum parathormone is elevated.

The GP takes into consideration the risk factors for rickets, clinical findings and investigation results, and confirms a diagnosis of vitamin D deficiency rickets. The GP is satisfied there are no features to suggest other clinical variants of rickets, and decides to treat the child with oral vitamin D.

Problem

Vitamin D deficiency in growing children – before the closure of the epiphyses – leads to rickets, whereas the manifestations are termed osteomalacia in adolescents and adults. The main causes of deficiency are inadequate exposure to sunlight and poor dietary intake of vitamin D-rich foods. Asian and African children are at greater risk, vegetarian diet and prolonged breastfeeding without vitamin D supplementation in pregnancy and during breastfeeding are additional risk factors.

Although vitamin D deficiency caused by poor nutrition is the most common cause of rickets in children, there are other clinical variants of rickets. Vitamin D or calcium-deficient rickets can be a result of malabsorption of vitamin D through coeliac disease, and can also be caused by liver disease or treatment with some anticonvulsants, which affect the metabolism of vitamin D. In rare cases, ‘end organ’ resistance to vitamin D can cause rickets. There are a number of causes of phosphate-deficient rickets, and genetic causes of rickets are rare but known.

Clinical features

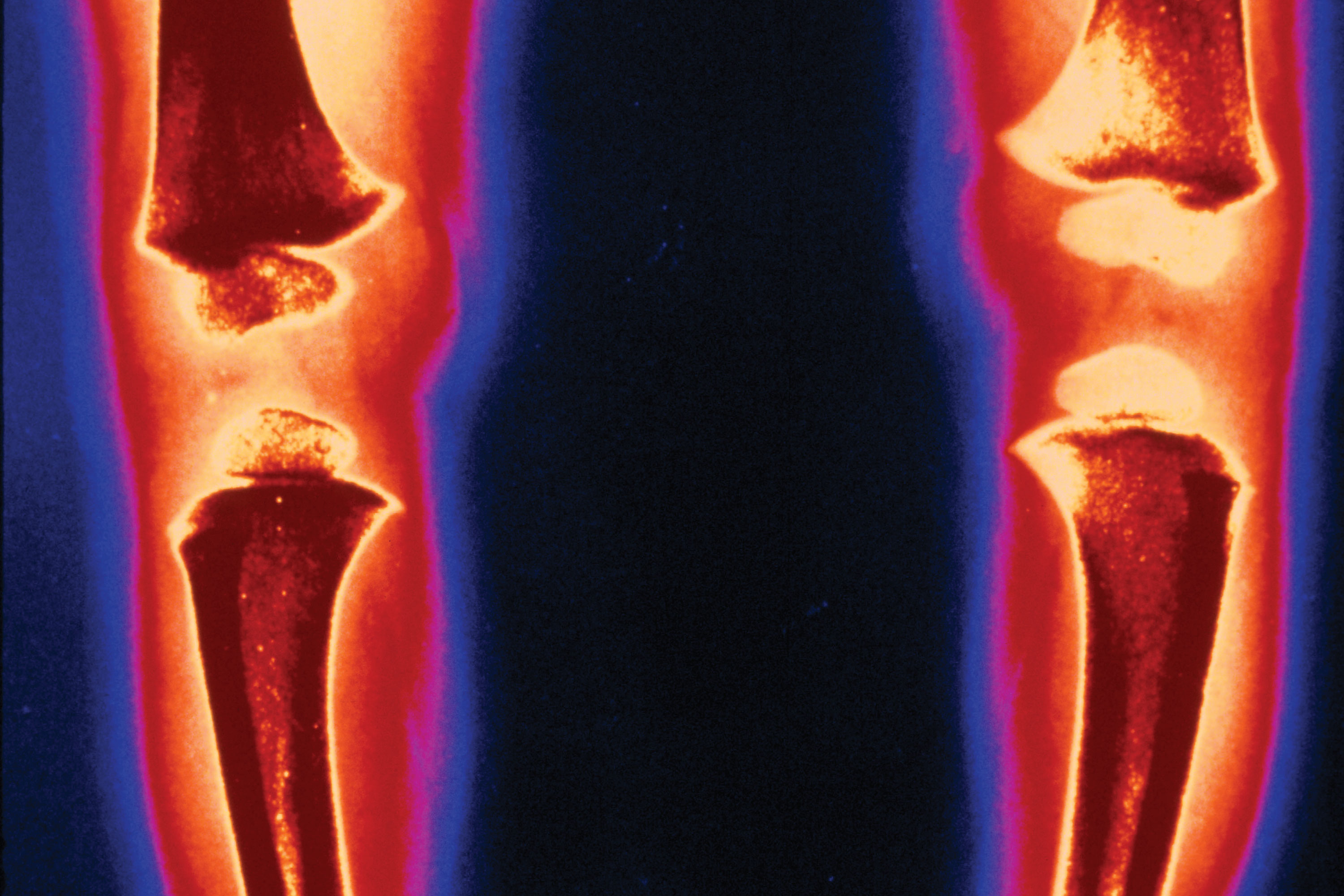

Vitamin D deficiency does not always manifest with florid clinical features of rickets, and children may present to primary care with poor growth, tiredness and vague aches and pains. When the deficiency is severe and is of sufficient duration, osseous changes of rickets predominate. Infants could present with large anterior fontanelle where closure may be delayed until after two years of age. ‘Beading’ of the ribs due to enlarged costochondral junctions is palpable and sometimes visible. Toddlers exhibit the appearance of swollen wrists and ankles due to epiphyseal enlargement. Bending of the softened shafts of the femur, tibia and fibula result in bow legs or knock knees. Poor growth, delayed eruption of primary dentition, low muscle tone and delayed motor milestones may also be presenting features.

Diagnosis

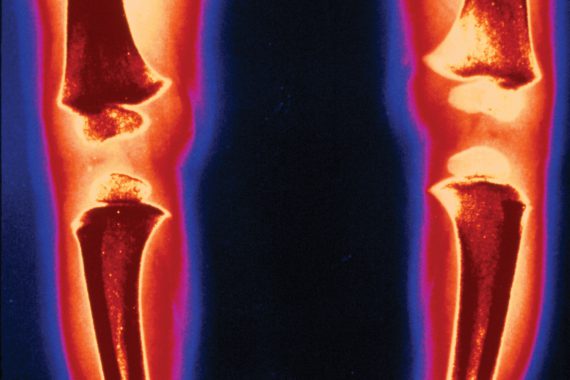

The diagnosis of rickets due to vitamin D deficiency is based upon history – where the patient has had inadequate exposure to sunlight, or a diet low in vitamin D – and the characteristic clinical signs of the condition. It is confirmed by biochemical tests – serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D levels less than 25nmol/l, and low serum phosphate with normal or low calcium. Alkaline phosphatase is always elevated. Parathormone levels are elevated and may help in differentiating vitamin D deficiency from other rarer types of rickets. While the characteristic radiological features of active rickets can confirm the diagnosis, seen as the cupping and fraying of the distal ends of the radius and ulna, and metaphyseal enlargement, it is not always necessary to request wrist X-rays prior to starting treatment unless atypical clinical or biochemical features suggest another cause for the osseous findings.

Management

Vitamin D deficient rickets is eminently preventable using a combination of maternal vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy and breastfeeding, especially in high-risk ethnic groups, and infants receiving at least 400IU of vitamin D as a supplement with adequate diet and exposure to sunlight. GPs should be aware of national and local prevention programmes in their populations, like the Healthy Start vitamin vouchers.

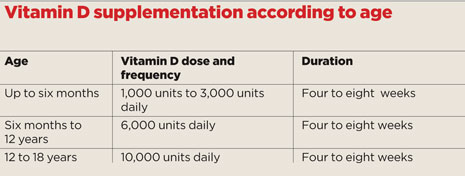

Clinical rickets will require treatment with high-dose vitamin D, and several regimes for treatment are noted in literature. The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health recommend the treatment regime in the box (above) with a liquid preparation of colecalciferol 3000IU/ml. Calcium supplements may also be required, if serum calcium levels are low at diagnosis.

A clinical review one month after starting treatment is recommended, and repeat vitamin D, calcium and phosphate levels after at least six weeks of starting treatment. If biochemical results do not demonstrate improvement – a transient fall in serum calcium levels is normally observed in some cases of vitamin D treatment – you should consider the possibility of a compliance problem or the possibility of rickets secondary to another cause, and refer to a paediatrician. It is recommended that children with symptomatic vitamin D deficiency should continue long-term low-dose supplements at a dosage of 400IU/day, until the completion of growth or unless lifestyle changes regarding diet or sun exposure are assured.

Dr Minoo Irani is a consultant paediatrician at Berkshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust and national lead for the NHS Alliance Specialists Network.

Key points

• Nutritional vitamin D deficiency is the most common cause of rickets, but there are other causes, such as coeliac or liver disease

• Vitamin D deficiency may present with vague symptoms in childhood, such as poor growth, tiredness and aches and pains

• The diagnosis is confirmed biochemically with serum 25-hyroxy vitamin D levels less than 25mmol/l and low serum phosphate, normal and low calcium and elevated alkaline phosphatase and PTH levels

• X-rays are not always required prior to starting treatment