october gabapentin 2017 cover image 3×2

GP prescribing of pregabalin and gabapentin has been rising over the past decade, soaring 88% since NICE recommended gabapentinoids as first-line treatment in 2013.

But this trend is set for a complete turnaround. Experts, official bodies and researchers are coming round to the idea that GPs should radically scale back the use of gabapentinoids, with the increase in prescribing being described as a ‘disaster’.

The drugs, they say, are causing adverse effects especially when used with opioids, they are routinely misused and, importantly, their efficacy is low.

The last few years have also seen a spike in gabapentinoid-related deaths.

The Home Office has told Pulse that it will ‘shortly’ be publishing plans to place the gabapentinoids on the controlled drugs list, which would prevent repeat dispensing and stop GPs from prescribing them for more than 28 days at a time.

Prescriptions increasing

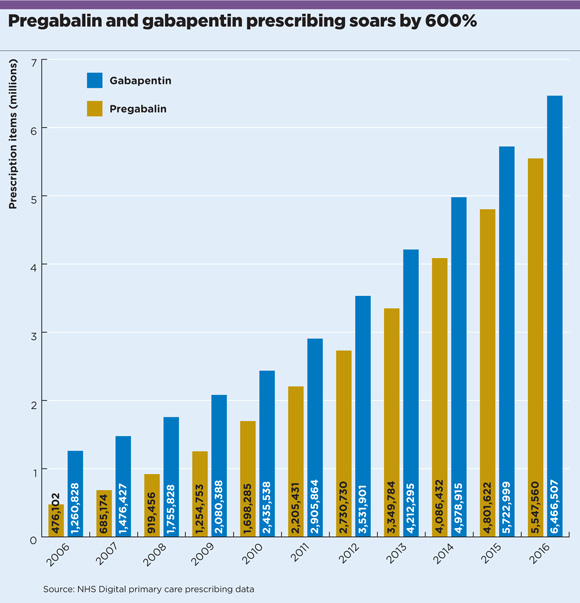

NHS Digital figures show NHS primary care prescriptions of pregabalin have increased more than ten-fold, from less than half a million in 2006 to just over 5.5 million in 2016. Gabapentin prescriptions have risen by more than 400%, from just over one million to 6.5 million over the same period (see chart).

Much of this increase has been driven by NICE’s advice on managing neuropathic pain. Its most recent guidelines, published in 2013, suggested GPs consider gabapentin or pregabalin as initial treatment, following on from its 2010 guidance, which recommended amitriptyline and pregabalin.

This has been part of a wider drive in pain management, starting in the 1980s, with the World Health Organization’s ‘analgesics ladder’, which made it more acceptable for GPs to prescribe potent drugs, such as opioids, at stronger doses.

But now experts are turning against this approach. As Pulse reported earlier this year, the backlash towards opioids is well under way, with the BMA and the RCGP launching reviews into their use.

Pregabalin causes a high in some users – Professor Les Iversen

The New England Journal of Medicine recently proclaimed a ‘North American opioid crisis is being caused by a false perception that there was a low level of addiction for opioids.1

And it seems gabapentinoids may be next to come under scrutiny.

NHS England first issued guidance on gabapentinoids back in 2014, warning ‘the drugs can lead to dependence and may be misused or diverted’. Now, a series of studies are urging GPs to consider alternative analgesia.

Researchers from the University of Kentucky in the US, published a study in Addiction, which found that misuse of gabapentin was at a staggering ‘40-65% among individuals with prescriptions’.2 They said: ‘An array of subjective experiences reminiscent of opioids, benzodiazepines and psychedelics were reported over a range of doses, including those within clinical recommendations.’

gabapentin prescribing soars 580x603px

This was followed by a Cochrane Review in June this year, which found gabapentin ‘can provide good levels of pain relief to some people with postherpetic neuralgia and peripheral diabetic neuropathy’, but added: ‘Evidence for other types of neuropathic pain is very limited… Over half of those treated with gabapentin will not have worthwhile pain relief but may experience adverse events.’

Also writing in Addiction, in May this year, researchers from the University of Bristol suggested GPs consider alternatives to pregabalin and gabapentin after finding the recent substantial increase in prescriptions to be closely correlated with a rise in the number of deaths associated with gabapentinoids in England and Wales, with a 5% increase in deaths per 100,000 increase in prescriptions.

Figures released in August from the Office for National Statistics underline these concerns: in 2012, there were four deaths related to pregabalin; in 2016, the number was 111. It’s a similar story for gabapentin; eight deaths in 2012 compared with 59 in 2016. Most of these result from mixing the drugs with heroin or other opioids, but some misuse them in other ways.

Psychotropic effects

Most experts agree that controlled status is needed as a minimum. GPC clinical and prescribing policy lead Dr Andrew Green says: ‘It has become increasingly clear over recent years that these drugs have a significant potential for dependence… We would support this change in legislation, which brings these drugs into line with others with similar problems.’

Dr Steve Brinksman, clinical director of drug and alcohol treatment professionals group SMMP and a part-time GP in Birmingham, says that the drugs have particularly worrying interactions with opioids, with which they are often prescribed for pain – notably an ‘increased risk of depression of the central nervous system’.

He adds: ‘They have psychotropic effects, which means patients are likely to continue taking them even if they are not proving effective. They probably do have a withdrawal effect too, although that has not yet been proven conclusively.’

Professor Les Iversen, chair of the Government’s Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD), says the case for controlled status is now clear. He says that, in conjunction with antidepressants, gabapentinoids ‘can cause drowsiness, sedation, respiratory failure and death’. On its own, ‘gabapentin can produce feelings of relaxation and euphoria’ while ‘pregabalin causes a high in some users’. However, side-effects include chest pain, wheezing, vision changes and hallucinations.

Patients will need prescription reviews every 12 weeks – Dr Alun George

Professor Iversen’s group wrote to the Home Office in January 2016, calling for the drugs to be controlled. And Pulse can reveal the Government has taken this call seriously. Minister Sarah Newton tells Pulse: ‘We have conditionally accepted the ACMD’s advice to control pregabalin and gabapentin as class C drugs, subject to a public consultation, which we will launch shortly.’

This stance was supported by the BMA’s annual conference, which earlier this year passed a motion calling for the BMA to lobby the appropriate authorities to make pregabalin a controlled drug, noting its ‘contribution… to bullying and violence in prison populations’.

Some areas are ahead of the curve. NHS Barnsley CCG is one of a number that has been advising prescribers to ‘consider the misuse before prescribing pregabalin’.

But while the evidence does indicate the need for a new approach, the proposed change is likely to mean additional workload for GPs. If gabapentin and pregabalin are to be categorised as class C drugs and placed under schedule 3 prescribing regulations, it will mean they cannot be repeat dispensed and prescriptions will be valid for a maximum of 28 days.

Dr Alun George, a GPSI in substance misuse in Leeds and clinical development director for substance misuse charity DISC, goes even further, saying patients will need ‘at a minimum’ prescription reviews every 12 weeks.

And pregabalin is also indicated for general anxiety disorder and epilepsy, which could make reclassification problematic. Dr Martin Johnson, RCGP clinical lead for pain and vice-president of the British Pain Society, suggests there is ‘some concern from the epilepsy world’. He says: ‘Patients are asking why they should be compromised and have to visit a GP every 28 days.’

Complications

There is another complication. Pregabalin has been off patent for epilepsy and anxiety for some time, but is only just coming off patent for neuropathic pain – by far its most common indication. This follows a lengthy trial over whether Pfizer held a ‘second patent’ for its drug Lyrica in neuropathic pain, and means the price of pregabalin fell by 97% between July and August, making it more attractive for commissioners – just as moves are being made to control its use.

There is also a significant dissenting voice on the dangers of gabapentinoids. Professor David Nutt, Professor Iversen’s predecessor as ACMD chair, tells Pulse: ‘I am not certain that there is significant recreational use of gabapentinoids other than by people who use other recreational drugs – so controlling them under the 1971 Misuse of Drugs Act is unlikely to impact on the health of those users; indeed it may encourage a switch to more risky drugs such as synthetic cannabinoids.’

But some GP are arguing for an even more radical approach to this problem.

Glasgow GP and long-time overtreatment campaigner Dr Des Spence writes in Pulse this month: ‘We need an immediate moratorium on prescribing. Take these medications off repeat and review these patients. But I would go further, and suggest lettering your local pain clinics stating you are no longer going to initiate opioids and gabapentinoids, even if they recommend them.’

Dr Spence adds: ‘Prescribing has gone through the roof in the past five years. This is not GPs’ fault. There’s been a real trend towards medicalisation, including the opioids. It’s been a real disaster.’

But long waiting times for counselling and physiotherapy appointments mean GPs are faced with a lack of alternatives for patients in severe pain.

As the arguments over these drugs continue, there is a real risk that GPs will be caught in the middle.

What does controlled drug status mean for GPs?

The Government’s plan, which would see gabapentin and pregabalin categorised as class C drugs and placed under schedule 3 prescribing regulations, would mean the drugs could not be repeat dispensed and prescriptions would be valid for a maximum of 28 days.

There is a good practice requirement that the quantity of Schedule 2, 3 and 4 controlled drugs be limited to 30 days’ worth. In cases where prescribers believe a prescription should be issued for a longer period they may do so but will need to be able to show a clinical need and that it would not cause an unacceptable risk to patient safety, according to the Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee.

It contravenes the 1971 Misuse of Drugs Act to possess any drug belonging to Schedule 2 or 3 without prescription or lawful authority.

References

1 Leung T et al, 1980. N Engl J Med 2017; 376:2194-2195

2 Smith R et al, 2016. Addiction. 2016 Jul;111(7):1160-74

Pulse July survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens