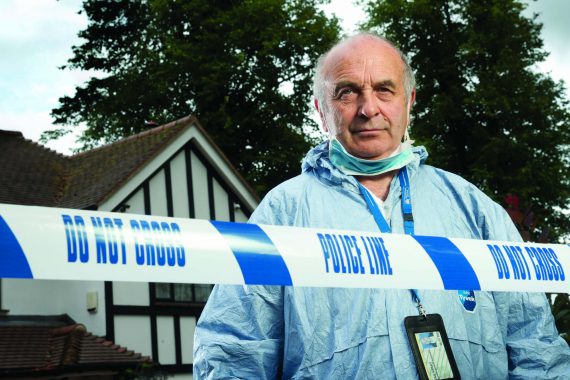

Working life: A shift as a forensic medic

Profile: Dr Clive Bailey

Roles: GP partner at 20,000-patient practice; forensic medical examiner; GPSI in occupational medicine; GP educator

Hours worked per week: On average, six sessions at GP practice and three six-hour shifts as FME

06.30 On arrival at the police station I’m asked to see a detainee who is suspected of common assault on his wife. He resisted arrest and was subjected to CS gas spray after threatening officers with a knife. He claims he was punched by police and shows me bruises to his face.

He tells me he had been drinking heavily and appears still to be under the influence of alcohol. I carry out a head-to-toe examination and document all injuries on a body-mapping pro forma. I advise a change of clothes for the detainee and fresh air in the custody suite to clear the CS crystals, which are causing irritation to staff in the vicinity.

I also advise on his fitness for detention and when he can be interviewed. My notes are kept privately and I communicate advice both verbally to custody staff and by record on the police computer system.

I have been working as a forensic medical examiner (FME) since 2005 when we lost our out-of hours contract and I was looking for a new challenge; I did a one-week residential course and took up an assistant FME post, then qualified for membership of the Faculty of Forensic and Legal Medicine (FFLM) in 2008. I now cover custody suites across south London.

07.30 I attend a detainee who was arrested on suspicion of threats to kill. He has a history of severe depression and self-harming and is also a heroin and cocaine user. Previous custody medical records reveal he has attempted hanging and been on a methadone detoxification programme in the past. I carry out a physical and mental health assessment and decide he is not sectionable under the mental health act but is vulnerable, which could lead to a false confession in a police interview. In order to protect him, I recommend an appropriate adult should be present during interview and that he is moved to a camera cell with 30-minute observations.

08.30 I’m called to another station to attend a young man who has been arrested for a public order offence and taken directly to the cell, as he has been uncooperative, aggressive and violent to police officers. When I introduce myself I am met with a torrent of verbal abuse. It is impossible to engage in meaningful dialogue and his behaviour is too unpredictable to carry out a clinical examination. There are no signs of significant injury; I recommend 30-minute checks in a camera cell and a follow-up examination in four hours.

I examine the three arresting police officers, who have been assaulted and injured. I record their injuries on a body map chart and make an entry in the police record book, giving advice about the injuries, treatment given and fitness for duty. I am not witness to any of the events and it is important to maintain an independent and impartial position.

10.00 My next call is to a residential address where a middle-aged man has been found dead in the bathroom by neighbours, with what police officers describe as unusual patches of hair loss. When I arrive there is a crime scene in progress; I’m asked to put on a forensic suit to prevent contamination of the scene.

After a short briefing from the police I enter the house, check for potential hazards and carry out an external examination of the body. I note some areas of scalp alopecia. I relay this information to the police and my opinion that there is no evidence of foul play. I certify life extinct and ask the police to contact HM coroner.

11.30 For the last hour of my shift I see detainees who require treatment for asthma, hypertension, diabetes and epilepsy, all common conditions in this population.

I would recommend the role of FME to any GP. The work requires some degree of resilience as the hours can involve nights and weekends, but the rewards of treating and supporting vulnerable people at their lowest ebb cannot be overstated.

For more information, visit the Faculty of Forensic and Legal Medicine website.

Visit Pulse Reference for details on 140 symptoms, including easily searchable symptoms and categories, offering you a free platform to check symptoms and receive potential diagnoses during consultations.