The patient record has been a cornerstone of the GP-patient relationship, with practices traditionally determining who is able to access this information.

But as the NHS blurs traditional boundaries between primary and secondary care, more and more organisations across the country are being allowed access to records. GPs remain the legal guardians of the records, but their ability to carry out their statutory duty to inform patients about who has access to them is diminishing, potentially putting them in jeopardy.

NHS plans for healthcare organisations to work more closely with one another often depend on these organisations sharing patient information, including GP records.

In most cases, the changes to access are justified and justifiable: doctors in A&E and urgent care having a complete medical history can be the difference between life and death.

Unauthorised access

But incidents of data ending up – or potentially ending up – in the wrong hands have been plastered over newspapers’ front pages. These include the NHS Information Centre – now called NHS Digital – handing NHS patient data over to insurance firms for a nominal fee. More recently, the home office has signed a ‘memorandum of understanding’ to gain access to personal details from GP records in an effort to tackle illegal immigration.

In March, Pulse revealed the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO)had raised ‘compliance concerns’ about the sharing model used by one of the most common GP IT systems, SystmOne. The system allows all its users to access the records of any other SystmOne user. As a result, 6,600 organisations have access to records, including the Yarl’s Wood immigration removal centre and police station custody suites, and this list is changing daily.

Patients have become more aware of data sharing

Dr Neil Bhatia

The extent of this sharing could potentially put GPs in breach of the

Data Protection Act (DPA), which requires that they be able to explain to patients exactly who their data are being shared with and why.

There are safeguards in place – only individuals with a registered smartcard (normally ‘senior clinicians’) within these organisations are able to access the records without the patient’s consent. Such access is only for use in an emergency and any attempt to access the record will be notified to the patient’s practice.

And TPP is currently attempting to make modifications to its SystmOne technology to help GPs who use that system comply with the DPA.

But this example highlights the tension between data sharing to improve patient care and GPs’ duties under data protection legislation.

So far, GPs have avoided falling foul of the DPA. But, as data sharing increases, and with it patient awareness, experts expect to see legal action against practices.

Phil Booth, coordinator of independent data-monitoring charity medConfidential, says practices must ensure patients can find out who has access to their records and be obliged to explain that patients can object to any of their data being shared. ‘If they don’t do those two things, GPs are open to being sued,’ Mr Booth warns.

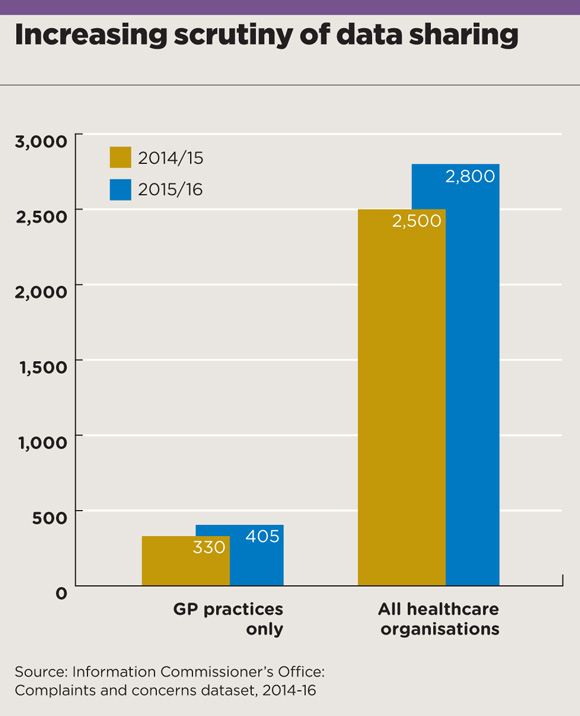

And already, the ICO is increasing its scrutiny of GP practices’ data-protection processes. Analysis by Pulse shows that in 2014/15 around 330 practices had their procedures assessed by the ICO after concerns were raised, or after the practice itself self-reported issues. In 2015/16, this figure had risen to 405, although only a minority required further action.

This is partly fuelled by the growing numbers of practices signed up to local sharing arrangements, which means local healthcare organisations can access patient records.

Rolling out this kind of arrangement across the country is essential to the Government’s plans for the future of the health service. NHS England wants to create new organisations that provide GP, hospital and community services under a single banner, and the sharing of patient information is a key prerequisite. It is also essential for federations of GP practices offering routine appointments at evenings and weekends as the Government pursues its plan to roll out a seven-day NHS.

Indeed, NHS England said in the update to its Five Year Forward View1 that all A&Es, urgent treatment centres and electronically prescribing pharmacists will be covered by local sharing arrangements for GP records by December 2017.

And the CQC encourages this. Its inspectors assess whether ‘staff have all the information they need to deliver safe care’, including appropriate sharing across integrated care teams. The GMC’s Confidentiality: good practice in handling patient information guidance2, which came into force on 25 April, is clear that ‘most patients expect that relevant information must be shared with the direct care team [whoever is caring for the patient at that time] for the purpose of providing care’.

data sharing graph may2017 580x716px

The sharing of information in

this way can be very welcome development. TPP medical director Dr John Parry says his experience in out-of-hours showed it was ‘immensely powerful’ to be able to access records when a patient presents. He points out that ‘there have been some “never events” in custody suites, where people with medical conditions have come to serious harm because they didn’t know what was wrong with them’.

The ‘Leeds Care Record’, which creates a shared record across GPs and other local providers, has allowed GPs to ‘deliver better, safer care at time of contact’, according to GPC deputy chair Dr Richard Vautrey, a GP in the city.

Dr Vautrey says: ‘It’s helped both clinically and administratively. This includes accessing clinic letters that have yet to reach the practice, finding out about patients who have been admitted to hospital, or being able to check when follow-up appointments are.’

But the result is that patient information that used to be restricted to the GP’s consultation room may no longer stay there, and this has legal implications for practices.

Hampshire GP Dr Neil Bhatia, who runs a website that helps patients to understand data sharing, says patients are increasingly clued up.

Dr Bhatia says: ‘Patients have become more aware, particularly with the push to online access to their GP record and the plethora of local data-sharing schemes now springing up.

‘It tends to go in cycles – when the press produce stuff about data sharing or data losses then more enquiries happen.’

Wider access to GP records may make sense to the NHS, but practices will have to tread very carefully to ensure they fulfil their legal obligation to patients.

Who is getting access?

Seven-day hubs

Record sharing is essential for federations of GP practices offering routine appointments at evenings and weekends as the Government rolls out a seven-day NHS. A seven-day access hub in Leicestershire had to be temporarily halted in 2015 after CCGs discovered information-sharing agreements were not in place. It restarted when a safeguard was introduced ensuring practices had to give consent for patient records to be shared.

A&E

NHS England said in its ‘Next steps for the GP Forward View’ that by December 2017, ‘40% of A&Es and urgent treatment centres will have access to primary care records, mental health crisis and end of life plan information’.

Police and immigration centres

The ICO has raised ‘compliance concerns’ about the SystmOne data-sharing system, which allows any other organisation using the system to access GP records, including police custody suites and the Yarl’s Wood immigration centre. The list of organisations able to access records is changing every day, making it difficult for GPs to fulfil their legal data protection duties.

Care homes

As part of its ‘enhanced health in care homes’ strategy, NHS England wants to permit appropriate access to care records for care homes, to ‘allow data-sharing for planning of provision’. It adds that this will include ‘access to the care record’.

How GPs can avoid complaints over data sharing

- Be clear on the sharing arrangements that you are part of and explain these to patients. These include local sharing efforts and any secondary uses. If you use SystmOne, you can log on and view an up-to-date list of the organisations that can access patient data.

- Communicate this to patients. The Data Protection Act requires that practices make a reasonable effort to provide patients with clear information about where data are being shared, direct them to where they can get further information, and record any objections.

- Get patients’ explicit consent to share data where you can. This can be at new patient registrations or check-ups.

- Allow patients to see who has looked at their data. Both EMIS and SystmOne can now allow patients to audit this directly.

- Act on any indications of illegitimate record access. This is another requirement under the act. In SystmOne, healthcare professionals can ‘override’ patient consent – for example, if the patient is unconscious. Practices will be notified of such access and should investigate.

References

1 NHS England: Next steps on the NHS Five Year Forward View, 2017. tinyurl.com/FYFV-next

2 GMC: Confidentiality: good practice in handling patient information.guidance, 2017. tinyurl.com/GMC-patientinfo

Pulse October survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens