birthday cover image

Prime Minister Theresa May announced her ‘birthday gift’ to the NHS last month: a £20.5bn real-terms annual increase to the health service budget by 2023.

This has been widely welcomed and with good reason. It signals the end of austerity. With a genuine political will, this could put general practice back on a fairer footing.

But GPs should exercise caution. Because there is a good chance they will receive a modest slice of the birthday cake.

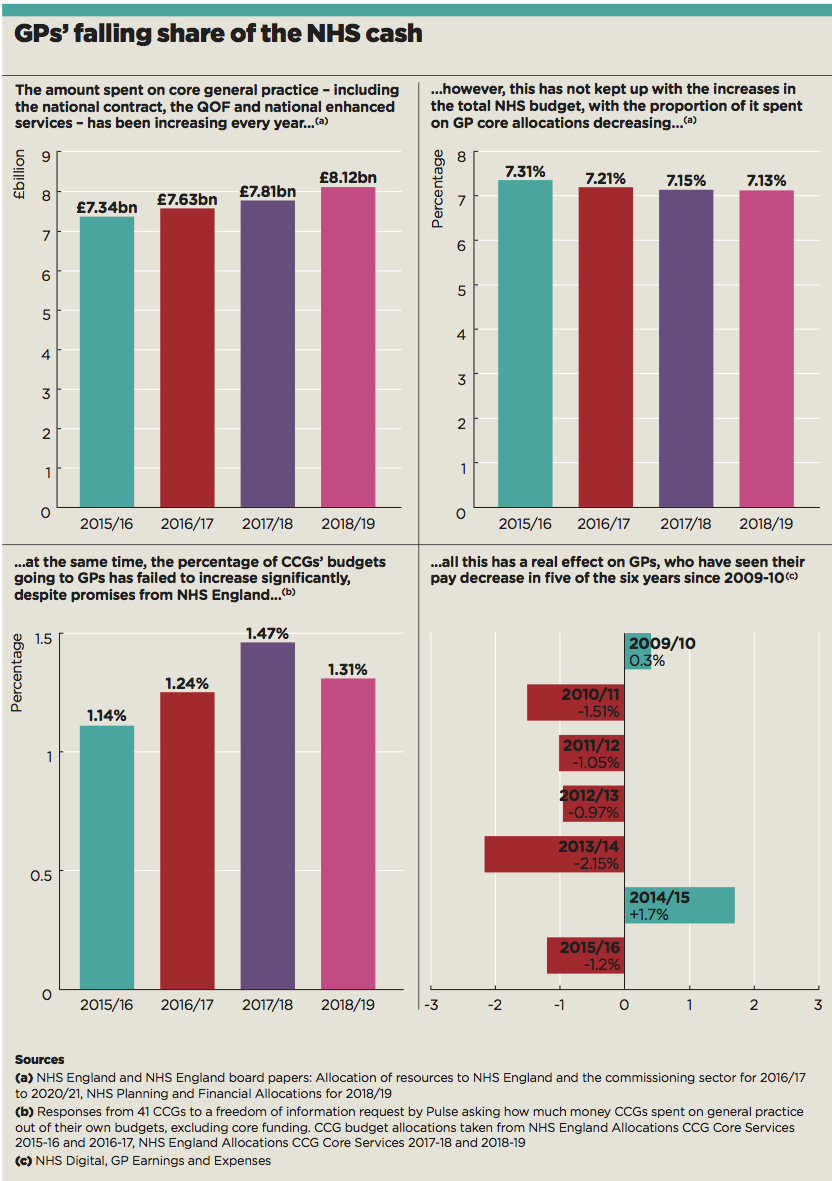

The percentage of NHS funding going to core GP work has been decreasing year on year. And that is from a relatively low starting point – GPs still receive just 7% of NHS England’s direct budget for their core service, despite doing as much as 90% of the work.

A Pulse freedom of information request to CCGs can also reveal that, despite NHS England’s claims that CCGs are topping up practice funding, they are only using around 1.3% of their budgets for general practice – a figure that has remained virtually static.

This is within an environment where ministers and NHS England leaders profess to be prioritising primary care. Indeed, NHS England’s GP Forward View support package in 2016 made an explicit commitment to increase the proportion of funding going into primary care to 10%.

gp funding proportion

NHS England claims it had almost reached this goal by 2016/17, citing a range of additional funding streams available to GPs. These include Health Education England funding for GP training, NHS England capital funding and drug cost reimbursement.

GP leaders say these are important but point out that practices themselves only see a small part of this. Yet they desperately need no-strings funding just to stay afloat. Only the most recent GP contract deals have included funding increases anywhere near inflation – but following years of inadequate settlements, this is doing little to improve recruitment or workload.

Between 2010/11 and 2015/16 – official figures are unavailable for 2016/17 and 2017/18 – GPs saw their pay decrease in every year but one.

In reality, GP leaders say, a disproportionate amount of funding vanishes into the black hole of acute trusts’ finances and, without a radical change of policy, that’s where most extra funding is likely to end up.

So will the PM’s £20.5bn a year increase by 2023/24 reverse these trends? The first question is whether it will actually materialise, as the PM says it is dependent on tax increases and a ‘Brexit dividend’. Even if it does, will it be enough to keep up with soaring demand across the NHS?

Many commentators have pointed out that the 3.4% annual increase is actually less than the 3.7% average over the NHS’s 70 years.

Meanwhile the Health Foundation and the Institute for Fiscal Studies estimate that a 4% rise is needed to improve services.

Nevertheless, the announcement has signalled a softening of the austerity policy that has been in place since 2010, and has been cautiously welcomed by the RCGP and the BMA.

BMA chair and London GP Dr Chaand Nagpaul says it is ‘refreshing’ that the Government has ‘finally conceded that our health service needs extra resources’. Dr Nagpaul says the BMA will be ‘scrutinising the detail of the new package’.

The exact details of the funding aren’t expected until the Budget this autumn.

We will scrutinise the detail

Dr Chaand Nagpaul

BMA GP Committee chair Dr Richard Vautrey acknowledges that all parts of the NHS will have their own claims on the extra funding, but says general practice has been ‘significantly underfunded’ over the past decade.

Dr Vautrey says: ‘We need that funding primarily to expand the workforce, deal with issues like indemnity, the premises problems many practices have, IT and infrastructure, and to ensure we have the capacity to be able to deliver good quality care.

‘We need proper investment in practices themselves, but we also need the right support staff.’

NHS England argues that in terms of funding general practice as a profession, it is ‘on track’ to deliver the GP Forward View’s commitment to boost GP funding by £2.4bn a year and increase the overall proportion of NHS funding received by general practice to 10% by 2020/21. It cites a number of funding streams in support of this claim (see box).

How money is spent on general practice

• Core contract: £7.63bn

• £1.8bn from CCGs in respect of:

– Local enhanced services (£534m)

– GP out of hours services (£426m)

– GP IT funding (£180m)

– Drug cost reimbursement (£590m)

– A share of the £171m funding (at £3 per head) for practice transformational support that CCGs can decide to spend in 2017/18 or 2018/19 or split between those two years.

• £300m from Health Education England for GP training.

• £220m from public health Section 7a funding.

• £200m of NHS England capital funding.

• £150m from DHSC to fund GP Systems of Choice.

• £35m from local authorities for public health provision.

Source: NHS England citing NHS Digital’s Investment in general practice 2016/17

However, a Pulse analysis has revealed that those streams that benefit practices directly – the core contract and CCG funding of enhanced services – have failed to keep pace with increases in NHS funding. The proportion of NHS England funding spent on core GP services has fallen from 7.31% in 2015/16 to 7.13% in 2018/19.

Pulse can also reveal that the proportion of CCG funding spent on general practice has remained largely static, despite the pledge in the GP Forward View that commissioners should contribute more of their funding to general practice.

A major analysis by Pulse of FOI responses from 41 CCGs revealed local commissioners only plan to spend around 1.3% of their budgets on general practice for 2018-19 – excluding money spent on the core GP contract. This is only a slight increase on the 1.24% spent in 2016-17 – when the GP Forward View was announced.

These funding decisions affect practices directly. Doncaster LMC chief executive Dr Dean Eggitt says his area has seen reductions to funding for locally commissioned services.’

‘One local enhanced contract has changed… it has had a 95p per head of population cut in its value, so we are doing the same work but getting paid less,’ he says.

The 1.3% of CCG budgets spent on general practice is ‘not even close’ to what is required, he adds.

Many of the problems stem from the continued emphasis on funding secondary care.

‘For all the rhetoric nationally about the GP Forward View, and moving care from the secondary to primary sector – and resources moving with that – that is not yet happening,’ Dr Eggitt says.

Secondary care has its own funding problems, with trusts themselves desperately in need of cash. A recent analysis by the King’s Fund shows 44% of all NHS trusts and foundation trusts in England are in deficit – although this is an improvement on the 66% in 2015-16.

A practice running out of money…doesn’t make headlines. But a hospital closing does.

Dr Peter Swinyard

Yet politicians are far more likely to bail out secondary care. Family Doctor Association chair Dr Peter Swinyard says: ‘A practice running out of money and having to close doesn’t make headlines. But a hospital closing does.’

Surrey GP Dr Joe McGilligan is a former chair of NHS East Surrey CCG. He agrees commissioners tend to favour secondary care: ‘General practice hasn’t got a core offer. You can’t count the widgets of primary care. You can’t say you’ve prevented this many illnesses, saved this many lives.’

The £1.8bn ‘Sustainability and Transformation Fund’, set up in 2016/17 to overhaul health and social care regionally, is a case in point. In January, the National Audit Office found it had been used to ‘improve the financial position of trusts’.

This is at a time when practices are facing their own troubles. Dr Swinyard says: ‘The average small practice is losing all sorts of things, such as seniority allowances, minimum practice income guarantees, all sorts of enhanced services that are not being commissioned by CCGs.

‘If you take my little practice, we’ve lost the equivalent of a full doctor’s worth of funding over the past five years. We can’t provide the service that we would like to provide and this means the patients don’t get the service they would like to receive.’

So GPs may fear they are unlikely to see much of the £20bn-a-year increase. But there are chinks of light. The £20.5bn cash injection does represent a shift in Government policy and, even if GPs’ share of NHS funding does not rise, they should still receive more in absolute terms.

And commissioners themselves now say general practice is a focus for extra funding. A King’s Fund poll of CCG finance leads in May found 79% said they would prioritise GPs if given extra money.

Even the health secretary appears to have acknowledged the discrepancy between acute and primary care funding.

Just before the PM’s announcement, Jeremy Hunt told the NHS Confederation conference that ‘one of the lessons of the last five years is we found pressures in the acute sector tend to suck in resources that then denudes transformation funding and transformation plans’.

He added: ‘So if we get a sustainable long-term settlement, we need to find a way of making sure that transformation funding is protected and that we really do have a structured programme to increase the capacity of primary care.’

This acknowledgement is a start, notwithstanding any concerns GPs will have about Mr Hunt attaching strings in the form of seven-day access and other conditions to any funding increases.

But until such statements are translated into a substantial increase in funds received by practices, GPs will be advised to put away the party poppers.

Where will the extra £20bn come from?

There has been much debate about how the Government intends to pay for its NHS birthday ‘present’.

When Prime Minister Theresa May announced the £20.5bn a year increase in funding, she suggested it would come from a ‘Brexit dividend’ – echoing the infamous pledge on the Vote Leave bus saying the £350m the UK sends to the EU a week could be spent on the NHS.

But the day after her announcement, during a speech at the Royal Free Hospital in London, the PM admitted taxes would have to rise.

She said: ‘The commitment I am making goes beyond that Brexit dividend because the scale of our ambition for our NHS is greater still. So, across the nation, taxpayers will have to contribute a bit more in a fair and balanced way to support the NHS we all use.’

The Government has given no indication so far of how much taxes will need to rise.

Health economists have previously cast doubt about how much difference this level of extra funding can make.

In May, the Health Foundation and Institute for Fiscal Studies warned in a report: ‘Our analysis suggests that UK spending on healthcare will have to rise by an average 3.3% a year over the next 15 years just to maintain NHS provision at current levels, and by at least 4% a year if services are to be improved.’

Health Foundation policy and economics analyst Ben Gerschlick reiterated to Pulse that the 3.4% rise will mean NHS services ‘stay broadly as they are and stem the deterioration’, adding: ‘There does need to be quite a healthy dose of realism about what we can do with this.’

Pulse October survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens