Being the subject of a patient complaint is probably one of the most traumatic events in any doctor’s working life.

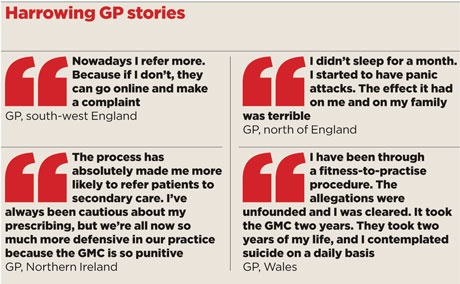

This GP’s reaction is typical: ‘I didn’t sleep for a month. I started to have panic attacks. The effect it had on me and on my family was terrible.’

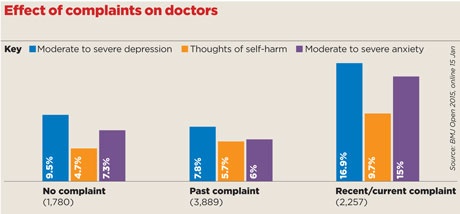

Now, a shocking new study has revealed the poisonous effect of complaints procedures on the mental health of doctors. The study of 8,000 doctors – the largest ever conducted in the UK – found that a sixth reported severe or moderate depression following a complaint, and many others reported anxiety and even suicide ideation.

The study, from researchers at Imperial College London, comes after a GMC review last year found 28 doctors had died by suicide during fitness-to-practise procedures.

The most worrying finding of this new study was the adverse effect on patient care. Eight in 10 doctors said a recent complaint changed the way they practise, while over one in four (26%) said they suggested invasive procedures against their professional judgment.

The vast majority of doctors showed ‘hedging’ behaviour after a complaint and a third became less committed and ‘worked strictly to their job description’.

The researchers’ conclusion was damning: ‘Our data also show the vast majority of doctors who took part in the study reported engaging in defensive practice.

‘This included carrying out more tests than necessary, over-referral, overprescribing, avoiding procedures, not accepting high-risk patients and abandoning procedures early.’

They added: ‘These behaviours are not in the interest of patients and may cause harm, while they may also potentially increase the cost of healthcare provision.’

‘More harm than good’

Lead author Professor Tom Bourne, professor of surgery and cancer at Imperial College London, explains the results – published last month in BMJ Open – may only show association and not causation, but they are still of ‘major concern’.

He tells Pulse: ‘The data show that psychological morbidity increases as the “complaints pyramid” is ascended, so it is lowest with informal procedures but much greater when the GMC is involved.

‘Morbidity is lowest in people who have not had a complaint, but have observed one – but highest when a complaint is ongoing.’

The researchers concluded that, as the majority of doctors who are reported to the regulator are not found to have a significant case to answer, the fitness-to- practise process ‘may do more overall harm than good in terms of patient care’.

This conclusion is borne out by the experience of those working with doctors who have been the subject of a complaint.

Professor Clare Gerada, former RCGP chair and medical director of the NHS Practitioner Health Programme (PHP) – the support service for sick doctors – says a complaint against a doctor can present a substantial risk factor for depression.

She says: ‘When we see someone at PHP who has been referred to the regulator we are very concerned. Even if the person is not depressed at the time, we consider that a referral is a massive risk factor for depression.’

She concurs with the view that this adversely affects patient care: ‘Complaints make doctors act defensively and this effect persists for long time, and makes them over cautious, not just in referring and investigations but in terms of spending longer with consultations.

‘There is a downside of complaints which can, paradoxically, harm patients.’

The study comes at an awkward time for the GMC. The regulator published an independent review in December of the deaths of doctors who had been undergoing a fitness-to-practise investigation between 2005 and 2013. It revealed that, over the eight-year period, 28 doctors had died from suicide while undergoing GMC investigations.

The review recommended several fundamental changes to fitness-to-practise procedures, including ensuring doctors feel they are ‘innocent until proven guilty’, setting up a national support service and teaching ‘emotional resilience’ during medical training.

The review’s recommendations have been accepted in full by the GMC. However, chair Professor Terence Stephenson recently told a parliamentary hearing that complaints were an ‘occupational hazard’ and emotional resilience training – similar to that undertaken by soldiers in Afghanistan – could help.

His comments provoked fury among GPs – with the story on the Pulse website receiving more than 150 comments.

GPC chair Dr Chaand Nagpaul says while GPs do need to be resilient, emotional resilience training is not the solution to the problem.

He adds: ‘This is not a war. What we need is to make the environment supportive for GPs. We know that a complaint and, in particular, an investigation into performance, is hugely damaging for GPs, not just in terms of stress but in terms of their ability to continue to provide care.’

Progress

The GMC says it will be looking at what further change is needed. Chief executive Niall Dickson says: ‘We know some doctors who come into our procedures have very serious health concerns, including those who have had ideas of committing suicide.

‘For any doctor, being investigated by the GMC is a stressful experience. Our first duty must be to protect patients but we are determined to handle these cases as sensitively as possible, to ensure the doctors are being supported locally and to reduce the impact of our procedures.

‘We have made some progress but we have more to do.’

‘It was pretty nerve-wracking’

I received the letter on Valentine’s Day 2014 from the GMC, saying it had decided to investigate a complaint.

The complaint was over a symptom I did not refer and it had some quite scary wording. Nothing was ever very clear – it was all ‘this could affect your fitness to practise’ and ‘this could lead to your licence being removed’. It was pretty nerve-wracking.

The GMC invites you to comment on the complaint in the initial letter. Having never had anything like it before, I was so shocked when I received it that I wrote back outlining what I thought had happened. Then I was advised by the MDU that on no grounds should I make any comment to the GMC because they immediately send it on to the complainant.

After that, it was just a case of me ringing the GMC to chase up. But the concern was always around the complainant and what they thought. No one ever asked me what I felt.

In my case, the GMC’s final report in June 2014 said no further action should be taken, so there was no panel hearing and the complaint wasn’t upheld.

No GMC support

One of the points on my report was that I shouldn’t assume that this particular symptom was harmless. But doctors assume symptoms like that are harmless every single day – am I now supposed to assume everyone I see is problematic and refer them?

I had no support from the GMC. It would have been nice to have someone to call for pastoral help. Essentially, if the complaint is upheld, you get to put your point across – in court.

But if, as in my case, it never gets to that point, you never get the chance to say anything: you’re just ‘under investigation’.

I now refer more, because while I worry that someone might rap me over the knuckles for referring too many cases to secondary care, I don’t worry that they’re going to strike me off the medical register for doing so.

Name and address supplied.

Pulse October survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens