GPs left to burn

The effects of GP burnout are increasingly stark, and familiar to many. Scores of GPs are leaving the profession or needing to take prolonged absences from work. There are even examples of GPs ‘falling apart mid-consultation’.

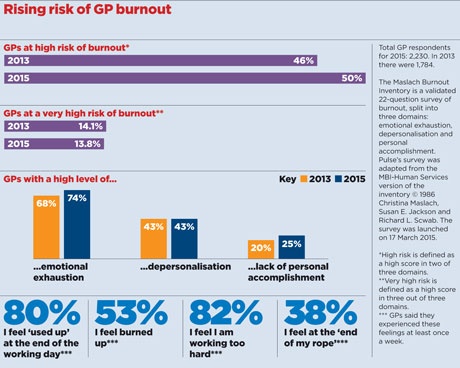

But the largest-ever analysis of GP burnout in the UK shows the situation is getting worse. Pulse’s survey of 2,230 GPs shows 50% are at high risk of burnout, up four percentage points from the same survey two years ago.

Three-quarters of GPs feel emotionally exhausted while 25% report a low sense of personal accomplishment. These shocking figures reflect NHS managers’ continued failure to provide the support they promised to struggling GPs. In fact, the few high-quality occupational health services available are being cut, with commissioners seeing them as a relatively easy way to save money.

Former RCGP chair Professor Clare Gerada, medical director of the Practitioner Health Programme (PHP) – a confidential mental health service for doctors in London – has no doubt about the crisis in GPs’ health.

‘The NHS at the moment is an industrial hazard, and especially for GPs.

‘Of course we go beyond the call of duty. But to do so every single day – as opposed to in an emergency – and to expect our colleagues to the same is causing great harm to GPs.’

Professor Gerada said PHP had been forced to shut its doors for six weeks in March after a ‘massive increase’ in demand, most of it from GPs.

Dismantling support

Pulse reported earlier this year that, in Devon and Cornwall, a gold-standard service, allowing GPs to self-refer for stress and burnout, had its funding pulled by the area team. The LMC was forced to implement its own insurance-style scheme to maintain a service.

In Lancashire and Cumbria, it is a similar story. LMC chief executive Peter Higgins tells Pulse occupational health services were ‘very good’, but NHS England scrapped them when the area team took on primary care commissioning and only partially reinstated them in Lancashire.

He says: ‘For most of Lancashire it dealt with any physical or mental problem – they’d do cognitive function testing. It was comprehensive and very good.

‘There wasn’t a specialist service for treatment… but it was a bloody sight better than we’ve got at the moment. [They] could then refer on to other services – so that was like a doorway in, and it was for all practice staff as well.’

Both counties are now pushing for a mental health treatment service for GPs based on the PHP model, which the LMC says would save money by ‘preventing doctors falling over the cliff and burning out’. So far, though, requests for funding from the CCG and area team have ‘drawn a blank’.

In Kent, prospects look similarly bleak.

LMC medical secretary Dr John Allingham says: ‘We are hanging on by the skin of our teeth. We have occupational health funding for next year, but nothing guaranteed going forwards.’

And this dismantling of key support services is likely to occur in other areas.

In Scotland, Lothian GP and GPC executive member Dr Dean Marshall tells Pulse there was a counselling service and occupational health ‘but now they’re talking about charging GPs for it’.

The only part of the UK that seems to be bucking the trend is Wales, where the Government is funding a free counselling service that offers up to six sessions.

But many areas have never had any support for GPs suffering from burnout and this has not changed, despite NHS England promising last year – after months of lobbying from Pulse’s Battling Burnout campaign – that it would commission a ‘high-quality’ occupational health service that all GPs could access.

A spokesperson recently told Pulse that: ‘Details of the occupational health offer for those on the national performers list are being developed, but we want to ensure that GPs have access to early occupational health assessment.’

But while NHS England stalls on its commitment, ever-higher numbers of GPs find themselves at risk of burnout.

Dr Daniel Mounce, a former GP in Bradford, left the profession ‘after falling apart mid-consultation’.

He says: ‘For me, leaving general practice has been like leaving an abusive relationship. The shaming and invective, the fear, the unreasonable demands were about driving down self-esteem.

‘I can’t quite believe I ever thought I could stick it for another 30 years.’

Guilt

Dr Valerie Dock says retiring from her London partnership four years ago for locum work on the Sussex coast was the ‘best decision I ever made’.

She says: ‘I almost feel guilty watching the partners where I work chasing their tails, becoming increasingly stressed with their increasing workload.’

And GPs are blaming themselves. One, who did not wish to be identified, tells Pulse: ‘Sometimes I think I’m just being soft, lazy, slow or just weak when I feel stressed at the end of the day.’

Even worse, singlehanded Doncaster GP Dr Shahzad Arif was slapped with abreach notice by NHS managers after burnout forced him take long-term sick leave.

Dr Arif tells Pulse he was ‘frustrated’ at the total absence of support. Only the efforts of the LMC and his practice team have enabled him to return.

He says: ‘I think it was perhaps something waiting to happen; there was a slight trigger that day because the practice had been unusually busy and I decided I need a break, I couldn’t go on.’

The area team is now helping, but Dr Arif’s case shows how bad it has to get before managers sit up and take notice.

The recent LMCs Conference voted for a ‘fully funded’ occupational health service for all GPs and practice staff. Even health secretary Jeremy Hunt last month said the issue of GP burnout needed to be tackled, and new GMC chair Professor Terence Stephenson told Pulse the regulator ‘absolutely supports’ the principle of rolling out a national psychological support programme for GPs.

Fortunately, the professionalism of GPs means they are protecting their patients from the effects of the struggle.

The survey found two-thirds of GPs say they are able to ‘deal effectively’ with patient’s problems. As Reading GP Dr Simon Ruffle says: ‘There’s hardly a day when GPs don’t make a difference to someone’s life. I know I did today. That’s priceless, uncountable, unQOFable and enough to keep us coming in.’

NHS England must now make good its promise and put in place the support that GPs’ dedication deserves.

Signs of burnout you should look out for

‘I never thought it would happen to me. I suppose nobody ever does.’ Comment on Pulse’s website, Jan 2014.

‘Burnout occurs when passionate, committed people become deeply disillusioned with a job or career from which they have previously derived much of their identity and meaning. It comes as the things that inspire passion and enthusiasm are stripped away, and tedious or unpleasant things crowd in.’ www.mindtools.com

The most damaging misconception we doctors acquire is that we are somehow ‘gifted’, with different wiring arrangements from those we seek to serve. The majority of us are high achievers and expect a lot of ourselves; we do not undergo the lengthy process of becoming doctors in order to deliver mediocrity.

Yet, if self-care matters for those we care for professionally, the same should apply to us. We are all people after all.

These are the five signs of burnout that I noticed in myself. If you have them, please do not wait to seek help:

• Frequent gastrointestinal colic, indigestion and irritability.

• Loss of self-compassion and an increasingly critical ‘inner voice’.

• Loss of interest in work areas that had previously given you deep satisfaction.

• Increasing emotional distance from those you love.

• An impending feeling of doom and complete lack of sense of control over your work-home life balance.

Dr Chris Manning, former GP, chair, Mental Health Group, College of Medicine, and convenor, Action for NHS Wellbeing

Pulse July survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens