An unequal race: How BME GPs face tougher hurdles

discrimination picture 3×2

‘The case of Dr Bawa-Garba has once again thrown the issue of race back into the spotlight. This is a watershed moment for the profession and is an opportunity for meaningful action,’ says Dr Farah Jameel, a BMA GP Committee executive member.

And the case does seem to have sparked an impetus for change.

The British Association of Physicians of Indian Origin (BAPIO) publicly accused the GMC of treating black and minority ethnic (BME) doctors ‘differently and harshly’, holding a special conference on the issue, which was attended by GMC chief executive Charlie Massey.

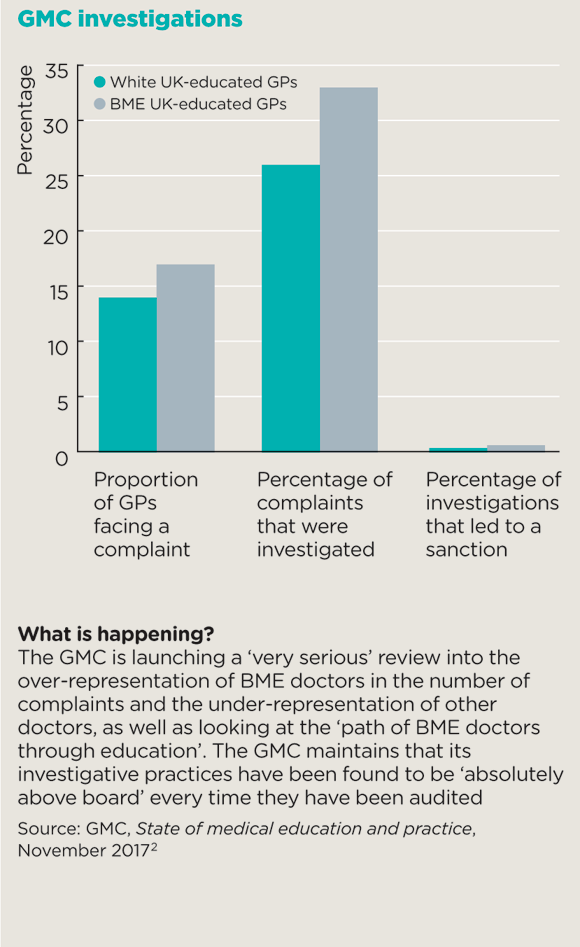

The BMA quickly followed suit, announcing a conference on the topic of BME doctors this summer, to look at different levels of attainment and referral for disciplinary procedures, bullying and stunted career progression.

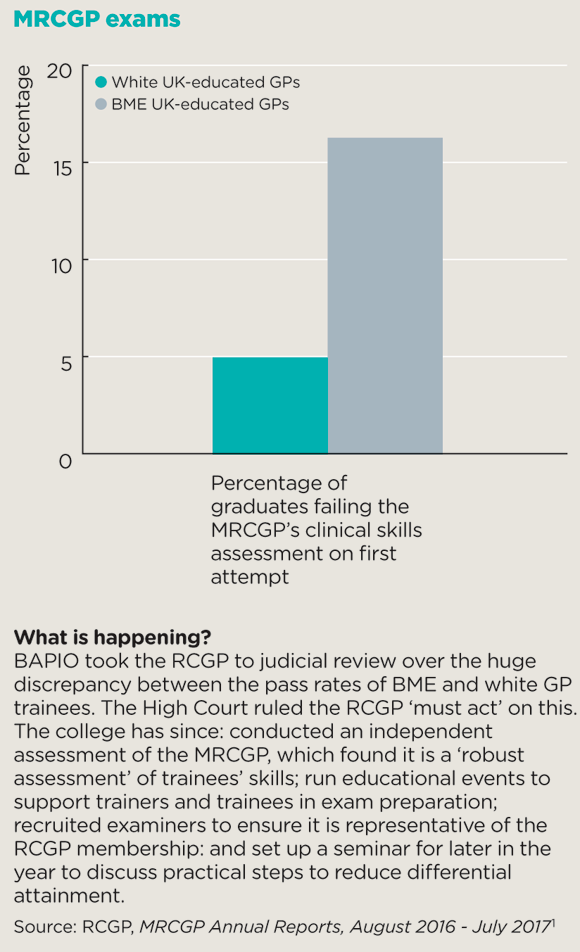

The GMC seemed to heed the strength of feeling, announcing at the Pulse LIVE conference in March a ‘very serious piece of work’ into how BME doctors are investigated.

gmc investigations box 580x947px

But it’s not as if race is only now becoming an issue. It has often been the elephant in the room in general practice and goes far beyond the overt prejudice BME GPs face from some patients.

Perhaps more importantly, BME GPs face worse outcomes throughout their careers.

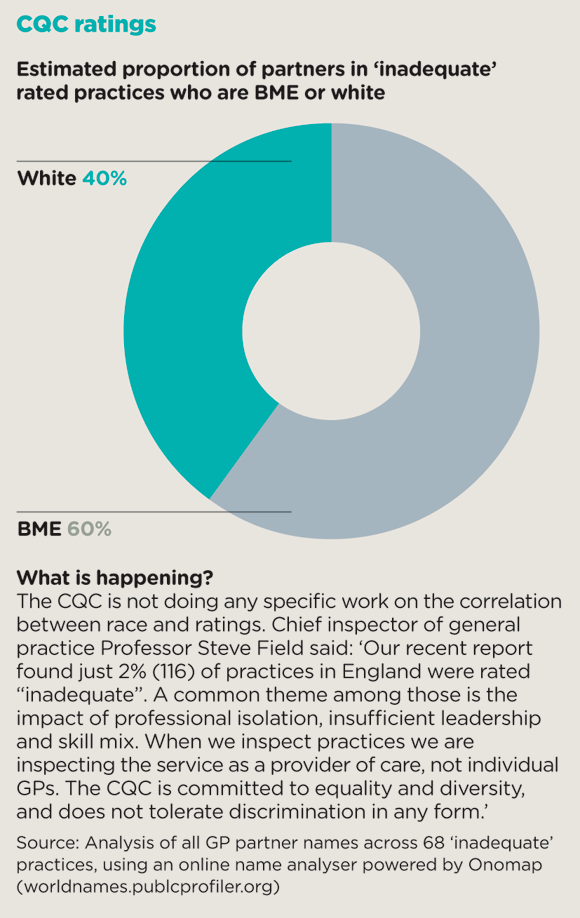

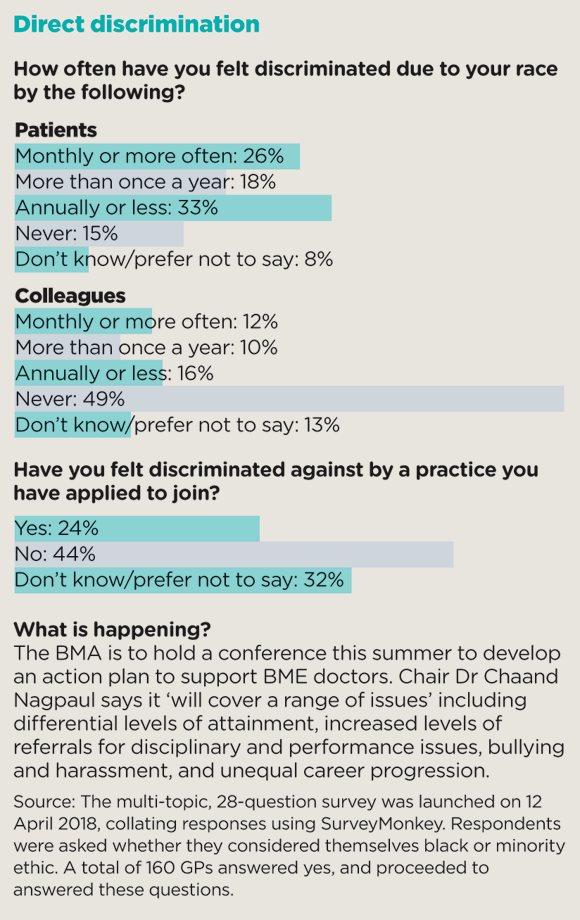

This can’t be written off as a problem for overseas-trained doctors who have had less exposure to UK general practice. A UK-educated BME GP trainee is more than three times as likely to fail the clinical skills assessment component of the MRCGP exam as a white trainee, and UK-trained BME GPs are 20% more likely to face a patient complaint and 30% more likely to be investigated by the GMC during their career than their white equivalents (see box). Seven of the nine doctors convicted of gross negligence manslaughter since 2004 have been BME. Pulse can also reveal that at least 60% of partners in practices receiving an ‘inadequate’ CQC rating are BME.

And this isn’t restricted to those of a particular origin: all non-white GPs have a tougher time, regardless of background.

While this is of course part of a wider societal issue, Manchester GP Professor Aneez Esmail – a leading expert on racism in the NHS – says: ‘Doctors are in a position where we look after people; it’s incumbent on the medical profession to be more sensitive to the issue of race.’

The effects of the problems faced by BME GPs reverberate across general practice. According to Professor Esmail, the numerous challenges can ‘lead to bad practice’, adding to the pressure on the profession. ‘BME doctors don’t engage as well as they could or should,’ he says. ‘In the end they think: “What the hell. I’ll just do my job and leave. I’ll never get recognised”.’ With BME GPs making up one-third of the workforce, the knock-on effect is significant.

mrcgp exam box 580x952px

Tackling the issue is essential for the future of the profession too. The BMA found that a BME medical student is more likely to become a GP than a white medical student. Dr Jason Sarfo-Annin, an NIHR academic clinical fellow and a GPST1 in Bristol, adds: ‘It is imperative that the whole of medicine, and general practice in particular, get a grip of this issue otherwise it could lead to BME sixth-formers being put off medicine.’

Yet it’s the GMC’s role that has caught much of the attention. The regulator has ‘lost a lot of ground’ in the wake of the Bawa-Garba case, says Stoke GP Dr Chandra Kanneganti, who is chair of the British International Doctors’ Association (BIDA) and a GPC member.

He asks: ‘Would what happened to Dr Bawa-Garba have happened to someone named Barbara Graham? Probably not. How can the GMC convince doctors that this case didn’t happen because she was Muslim and black?’

The GMC is making an attempt to address such criticisms by announcing a review into its treatment of BME doctors, led by Middlesex University research fellow Roger Kline – the author of the ‘snowy peaks’ study into inequality in NHS trusts – and Dr Doyin Atewologun, a faculty member at Queen Mary University of London’s school of business and management.

The review will look at the reasons why BME doctors are more likely to face complaints than their white colleagues.

This is a start – but BME leaders aren’t getting their hopes up. This is the latest in a long line of reviews yet BME GPs still face far worse outcomes than their white counterparts throughout their career. BAPIO president Dr Ramesh Mehta says: ‘We are fed up of hearing it’s a complex situation. There is obviously bias, which may be intentional or unintentional.’

The key point, say BME leaders, is the system works against BME GPs, whether they trained in the UK or overseas.

Research has shown BME GPs are more likely to work in deprived areas, have higher patient-to-GP ratios and practise in areas with high BME and immigrant populations. BAPIO has already raised the issue that a high proportion of singlehanded practices – which are more likely to get low CQC ratings – are run by BME principals.

cqc ratings box 580x918px

This isn’t through choice. According to Professor Esmail, BME GPs would – like many GPs – rather work in ‘salubrious leafy suburbs’ without the additional challenges. Yet they are often thwarted for a number of reasons. One is practical: historically, overseas GPs have been brought in to areas that have struggled to employ GPs, which tend to be deprived. This is happening once more, with the UK Government planning to employ 2,000 GPs from overseas to work in the most under-doctored areas.

The other reason is more insidious. A Pulse survey from April 2018 reveals around one in four BME GPs have felt discriminated against by potential employers on account of race.

These conditions make it harder to meet the processes and standards set out by the likes of the RCGP, the GMC and the CQC. Singlehanded GPs are being squeezed by the move towards larger practices. And, as the Bawa-Garba case also highlighted, doctors rarely get any credit from the GMC for working in tougher conditions, whether they relate to deprivation or recruitment problems.

There are also cultural differences among patient populations. For example, patients from India and Pakistan ‘would prefer the doctor to make decisions’, says Dr Kanneganti. ‘If a GP asks them, “what do you think is going on?” they will think the doctor doesn’t know anything.’

White NHS leaders do not understand the discrimination BME doctors face in investigations and exams

Dr Kailash Chand

The row over the CSA element of the MRCGP is illustrative of this failure to acknowledge the different environments in which BME GPs often work. Despite the RCGP taking measures to redress the balance, the gap between the pass rates of UK-trained white and BME doctors remains significant. The problem is the assessment is based on situations more often encountered by white doctors – more educated patients, who want to be part of decision making, with few communication problems.

‘In our inner-city practice, we have a 90% Asian population and if a trainee’s qualifying practice is there, they may not be a true representation of the kind of role players they have been tested on,’ says Dr Kanneganti.

This discrimination starts before university. ‘If you look at applications for medical school, there’s a bias against Asian doctors and there is definitely a bias against African-Caribbean doctors,’ says Professor Esmail. ‘There are very few Afro-Caribbean GPs, for example. They struggle to get into medical school.’ Research in 1998 using data from the Universities and Colleges Admissions Service found that non-white applicants were significantly less likely to receive an offer compared to white students, despite getting the same A-level results and Professor Esmail says little has changed.

It’s a similar case for the CQC. Professor Esmail, whose practice has a high BME population, says: ‘Some 40% of our consultations require a translator, so they have to be longer. We’re also in a deprived area, so we have huge morbidity problems anyway.’ Yet he says this wasn’t factored in as other vulnerable patients would be: ‘I don’t think the CQC really understood how complex and difficult it is to deliver care to this vulnerable group of patients.’

So what can be done? ‘White NHS leaders do not understand the discrimination BME doctors face in investigations and exams,’ says Dr Kailash Chand, a retired GP and a former deputy chair of BMA Council .

He adds: ‘In my view, inequality is a problem to be solved by those most likely to suffer from it. More BME leaders will bring a change of culture, transparency and openness to the system.’

There are positive signs, with CCGs leading the way. A Pulse analysis of CCG governing bodies reveals 17% of CCG board members are BME, in keeping with the 18% of BME staff in the NHS. And 36% of GPs on CCG boards are BME, again reflecting the percentage in the general practice workforce.

But BME GPs will need tangible change to convince them their problems – and contributions – are being taken seriously.

‘There are GPs of all backgrounds who are not very good – it’s not exclusive to BME doctors,’ says Professor Esmail. ‘There’s a narrow assessment of what general practice should be. I understand why, but the end result is BME GPs don’t get fully recognised for our work with very difficult and complex populations.’

• Additional reporting: Emma Rosser

What’s the evidence?

A 1993 study by Professor Aneez Esmail and Sir Sam Everington revealed that white applicants to a job were twice as likely to be selected as their BME counterparts. The researchers sent 46 applications for 23 advertised posts across a range of specialties. Eighteen applicants were shortlisted, of whom 12 had English and six Asian names.6

A 1994 study by Professor Esmail and Dr Everington revealed that between 1982 and 1991 BME doctors were 12 times more likely to be charged with indecent behaviour than white doctors in similar situations, with white doctors more likely to face the lesser charge of forming an improper relationship with a patient.7

A 1998 study by Professor Esmail, Dr Everington and Helen Doyle found 18 times more white consultants received awards in 1996 than BME consultants. It said: ‘A system that appears systematically to exclude a section of the consultant workforce from recognition and reward cannot be defended.’8

Another 1998 study by Ian McManus used anonymised data from the Universities and Colleges Admissions Service to study all applications to medical school during autumn 1995 and 1996 and found non-white applicants were significantly less likely to receive an offer across the whole range of A-level achievement compared with white students.9

A 2014 study by Roger Kline looked at the leadership of NHS trusts in London to assess progress against the Government’s Race Equality Action Plan and revealed the ‘snowy peaks of the NHS’. It found two-fifths of London’s NHS trust boards had no BME members at all. More than half either had no BME executive members or no BME non-executive members. The results were reflected nationally ‘in every respect’.10

A 2016 study by Professor Esmail and colleagues found 21% of GPs trained abroad, with most of these working longer hours and seeing more patients in deprived communities, but earning less than their UK-qualified counterparts.5

Pulse July survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens