‘My patient committed suicide while waiting for a section assessment after assaulting me and absconding,’ says one GP. Another recalls how a patient committed suicide after being referred to the local CRISIS team ‘who didn’t think he was suicidal’.

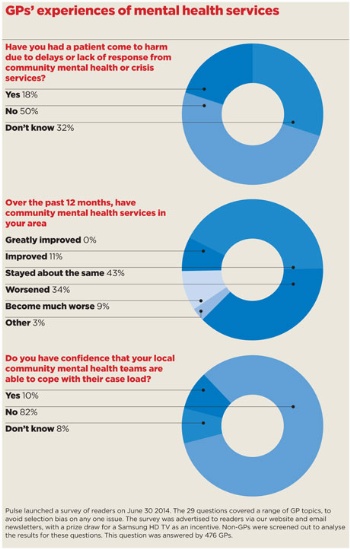

And these stories are typical. A Pulse survey of nearly 500 GPs reveals that a fifth have had a patient come to harm as a result of not being able to get appropriate psychiatric care. They tell the story of a service in crisis with patients facing long delays for specialist assessment, over-aggressive triage and many patients with mental health problems being failed by the NHS.

GPs have described patients in their care self-harming, ending up in A&E or being sectioned – and in some cases committing suicide as a result.

This comes as GP leaders call for an ‘urgent review’ of the funding of mental health services. The Government claims it is making progress on giving mental health parity with physical health, but the Pulse survey shows a completely different story. More than 80% of GPs say they have no confidence that their local community mental health teams can cope with their workload, and 43% say services have got worse or much worse over the past 12 months.

Many GPs say they are having to manage mental health issues outside their competence as the support in the community is not there.

Speaking anonymously to Pulse, a GP in Milton Keynes recalls how his patient, who was in and out of a mental health unit, killed himself in the shower while

supposedly under one-to-one supervision.

‘My concern initially related to the fact that the patient had been discharged to the GP for ongoing management, but we had little information at the time, and there were factors in the history that made him higher risk.

‘The father was clearly concerned, and it seemed there was little support following discharge. Only after an A&E attendance was the home treatment team involved, until he was admitted [for a second time].’

Another GP in the north east of England describes how a patient with a history of psychosis, self-harm and a reclusive life style, whom he referred, ended up taking a ‘significant overdose of paracetamol’. The mental health team made ‘little effort to engage’, the GP says.

‘The patient was offered an appointment at the psychiatric unit but did not attend, and was discharged from psychiatry follow-up with no indication of any further attempts to make contact.

A lady who was under the care of the mental health team had been delayed for follow-up and then couldn’t get hold of her care co-ordinator. In the meantime she took an overdose.

GP, Suffolk

‘The patient then took the overdose in early June, but did not present to hospital until a few days later with liver damage and GI bleeding. At this time, the patient had psychotic symptoms including hallucinations and paranoia.’

Meanwhile a West Midlands GP, who also spoke to Pulse anonymously, describes how delayed treatment of one young person with clear signs of early psychosis had devastating consequences both for the individual involved and their family.

The GP says: ‘I referred the case to the community mental health team, but they bounced it straight back saying “it doesn’t sound like anything serious”, without actually assessing him.

‘Within a matter of months he had to be sectioned because he had become psychotic and was a danger to himself and his family.

‘If they had seen him before, then potentially that crisis and the section – which has a significant impact on a person’s future prospects – could have been avoided.’

An overstretched system

GPs stress their criticisms are not aimed at colleagues in mental health teams, who they say are working under intense pressure and simply do not have the capacity to manage the ever-increasing number of cases in the system.

Instead, a lack of money and resources means the services are buckling under the pressure, which is having a knock-on effect on general practice.

And further recent cuts have not helped to ease the problem, with the national ‘tariff deflator’ guidance outlined by NHS England and Monitor earlier this year advising CCGs they should be aiming for a 1.8% cut in non-acute provider contracts in 2014/15, which include mental health services. This compares with 1.5% for acute sector contracts.

In June, Dr Felix Davies, a consultant psychologist who led one of the original Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) pilots, argued that talking therapies are now so overstretched they are ‘bursting at the seams’, due to big funding cuts as well as increasing expectations both in terms of the number of patients being referred and the range of psychological problems they deal with.

Have had to admit through A& E because of lack of response. The doctors are okay but they cannot cope with the workload

GP, London

The Milton Keynes GP says: ‘I’ve seen mental health services struggle to offer resources and support to patients and family, landing the extra pressure on primary care’s doorstep.

‘Equally, all services are being stretched by problems that should be diverted elsewhere, for example open-access counselling/CBT, employee support.

‘If GPs had greater scope to focus on need rather than patient demand, I’m sure more could be done earlier to avoid mental health crises.’

Lack of confidence

Pulse’s survey reveals long waits for both urgent and routine requests to local community mental health teams.

More than a third (34%) report patients having to wait two or more days for teams to respond to urgent requests for assessments. And 85% say they have to wait a month or more for a routine request.

The knock-on effect on general practice is so great that around 82% of GPs report being forced to manage patients outside their competence at least some of the time.

Half say they are forced to prescribe either often or all the time because their local psychological therapies service is unable to help a patient, and in excess of 80% say they have to do this ‘at least some of the time’.

Dr Tom Caldwell, a GP in Worcestershire, explains that for ‘minor’ everyday mental health problems, access for patients to talking therapies feels ‘glacially slow’.

He says: ‘I certainly feel that I am having to weigh the waits for talking therapies against medication when discussing options with my patients.’

I have had a patient come to harm and another commit suicide which were urgent referrals that were not seen in a timely manner

GP, Birmingham

Dr Elliott Singer, Londonwide LMCs medical director and a GP principal in Chingford, east London, says the survey findings resonate with GPs’ experience in his area. Despite recent improvements in communication with the local mental health team, he says the service is so stretched that GPs have been advised to send urgent cases to A&E.

Dr Singer says: ‘We’ve got the issue where, even though you may be able to speak to someone more easily, if you need an acute patient assessed for suicide risk or something like that, at the moment we’ve been advised to send them to A&E rather than the units, because there just isn’t the service available there for them to back up.’

GPs who responded to the survey also report mental health teams are increasingly discharging patients without first entering into formal shared-care agreements with practices, leaving patients with serious mental illness without regular reviews and psychiatric support in place.

These patients are highly vulnerable to relapse and, all-too often, GPs only become aware that a patient’s mental health is deteriorating when it reaches crisis point. Dr Singer agrees this has become a major issue, particularly over recent years.

He says: ‘In the past two years [the mental health team] has started discharging people they deem stable. That’s fine; if someone’s stable there is no reason why they shouldn’t be discharged, but we need to make sure the systems are in place so if they deteriorate they can be seen quickly and efficiently without further worsening of their mental health.

They bounced it straight back saying ‘it doesn’t sound like anything serious’ without actually assessing him. Within a matter of months he had to be sectioned

GP, Birmingham

‘But that is not happening, so these patients are not getting the appropriate treatment when they need it. And if they are upholding work, or whatever they are doing in their normal daily life, they lose all that again and they take quite a step back because of the delay in treatment.’

Dr Singer fears this is putting service users and the wider community in danger. He says: ‘It is a very high-risk strategy the trust is adopting. My concern is it’s a waiting game until a tragedy happens, if patients are not being monitored properly.’

Waiting time targets

The Government has pledged to raise the profile of mental health and achieve ‘parity of esteem’ for the care of mental and physical illness.

Since 2011, it has published wide-ranging national strategies on both mental health and dementia, and extended funding for the IAPT programme, launched by the previous Labour Government.

The Government has now mandated the introduction of waiting-time targets for access and treatment for patients with mental health problems from April next year and says it has asked Health Education England to ensure that GPs and other clinical staff have ‘thorough training’ in recognising the signs of mental illness.

Care minister Norman Lamb says he believes this will be ‘transformational’ and provide the impetus to redirect money into mental health.

In response to the Pulse survey, Mr Lamb says: ‘I want to build a fairer society with better mental health for everyone, which is why I am determined to achieve equality between mental and physical health services. Local decisions on funding must reflect this.

‘We’ve committed to introducing access and waiting time standards for mental health from next April and we’re improving mental health training for GPs so more people get the right support at the right time.’

Yet, despite the rhetoric, the Government’s aim is not being backed by investment.

Rebalance resources

RCGP chair Dr Maureen Baker argues that the way mental health services are funded needs to be urgently reviewed.

‘There is an urgent need to reassess the way funding is allocated so services in the community have adequate resources to deliver more proactive, planned care to patients with mental illness.

‘We are working with our colleagues at the Royal College of Psychiatrists to call for a rebalancing of NHS resources so that people with mental health problems get the care that they need and deserve.’

However, NHS England insists it is supporting CCGs to deliver the improvements.

Dr Martin McShane, NHS England’s director for people with long-term conditions, tells Pulse: ‘We must make sure patients get the right care as close to home as possible. While these decisions are made locally, we are supporting CCGs to deliver high-quality care and parity of esteem for mental health services – both of which are a priority for NHS England.’

But Dr Singer says the Government must shoulder more of the responsibility.

He says: ‘There is an issue for the Government in how they are resourcing mental health. It doesn’t grab the headlines until a tragedy occurs. It has lost funding over the years; unless that is reversed, things will deteriorate further.’

‘As ever, GPs have to patch the holes’

I have great sympathy for our medical colleagues working in mental health, who have many of the same problems we do. They work in a service that has been underfunded for years and which by its unglamorous nature finds it hard to attract new funds, which go to acute physical services.

It had been hoped that the increased GP role in commissioning might have allowed this situation to improve, but in fact there is so little flexibility within the financial situation that CCGs that would like to invest in mental health have been unable to do so and, as ever, it is general practice which has to struggle to patch the holes.

Dr Andrew Green is chair of the GPC’s clinical and prescribing subcommittee, and a GP in Hedon, East Yorkshire.

Pulse October survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens