Dr Helen Shires talks about when GPs should advise patients to get a swab while the testing system is under strain

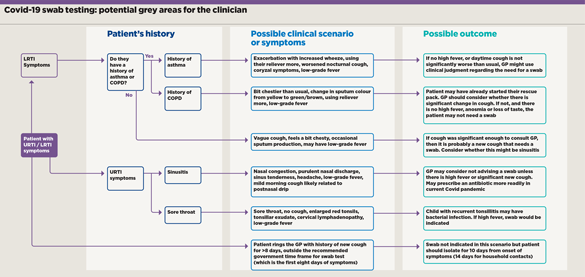

With the Covid testing system currently stretched, GPs may feel pressure to refrain from advising some patients to get a swab test. If a patient presents with coryzal symptoms or sore throat in the absence of cough, anosmia or loss of taste, the decision is simple as a swab would not be indicated anyway. However, there will be many situations that are less clear cut.

These are immensely challenging for the GP, as Covid-19 has been associated with an extremely diverse range of symptoms. A multicentre cohort study published recently in The Lancet1 of 582 children and adolescents with confirmed Covid-19, from countries all across Europe, demonstrated the most common symptoms to be fever (65%) and (not necessarily together) upper respiratory tract symptoms (54%). Approximately a quarter had evidence of LRTI and just under a quarter (22%) had gastrointestinal symptoms. Around 16% were asymptomatic.

Changing with age

Data analysed from Canada’s Public Health Agency2 for 121,795 cases of Covid in both adults and children reported that URTI symptoms were as common as fever up to age 59, becoming less common with increasing age beyond that – while fever was still reported in around 50% of Covid patients aged 60-69 years. Sore throat was a common symptom, reported in around 70% of younger patients and decreasing in frequency to around 50% up to age 69.

The presence of URTI symptoms therefore does not exclude the diagnosis of Covid-19. However, the absence of cough, high fever, anosmia or hypogeusia makes the diagnosis less likely.

When it comes to testing criteria, the definitions of ‘cough’ and ‘fever’ are hard to pin down. On the one hand, a new persistent cough in a patient who doesn’t normally cough may strongly indicate a swab. This decision can be more difficult when it comes to our asthma and COPD patients who usually have a cough that fluctuates at this time of year.

How do we decide if a fever requires a swab test? Government guidelines have replaced the previous definitive figure of >37.8°C with the vague term ‘high temperature’. One could presume this is to help the significant proportion of the population without a thermometer, although one might more cynically note that if the testing system is failing, the abolition of an actual figure gives clinicians greater ability to make clinical judgments. If you search the NHS website for the definition of a ‘high temperature’, it suggests a reading of 38°C or above.

In these times of Covid, many GPs have a lower threshold for prescribing an antibiotic for conditions such as possible tonsillitis, acute sinusitis, acute exacerbations of asthma and COPD. Patients who are mildly to moderately unwell without red-flag symptoms tend to be those we might deliberate over most when deciding whether to recommend a swab.

One such scenario is the asthmatic patient who usually experiences exacerbations in the winter months, which are normally treated with an antibiotic and oral prednisolone. Or the patient with COPD who is coughing a little more than usual and has noticed a change in their sputum from yellow to green, with thickening. They may have started taking their rescue medication. Patients with chronic lung conditions may also be used to chest infections at this time of year, and may not be happy if you tell them they need a swab when they have been shielding for months.

Further dilemmas

A similarly challenging scenario could be acute sinusitis in a patient who is known to suffer with their sinuses, along with a fever or a mild new cough that seems to be associated with postnasal drip. If you have seen the patient face to face or they have a thermometer, then an actual figure for their temperature will help guide you. ‘I’ve felt a bit warm, doctor’ gives you less to go on. How do you define their cough? Coughing first thing in the morning and just on occasion throughout the day may simply be to clear the mucus from a postnasal drip. On the other hand, it is a new cough, and the NHS website defines ‘a new, continuous cough’ as ‘coughing a lot for more than an hour, or three or more coughing episodes in 24 hours’. One GP might send this patient for a swab where another would not.

Anecdotally, most doctors agreed they would consider a fever of 38°C or above – or a convincing history of feeling hot and cold, shivery, having sweats or chills – as requiring a swab regardless. The patient who ‘felt a bit warm’ in the absence of a new cough or anosmia or ageusia would be considered less likely to warrant a swab.

One doctor applied the following rule to a new or worsened cough: if it makes the patient think, ‘oh no, here comes the next winter bug!’ it is likely to be significant enough for a swab.

As a GP in both daytime practice and urgent care, I personally choose to adhere to the government criteria for swab testing. My approach is influenced by the high number of Covid cases I have encountered in my region. But I might choose to differ in a case of sinusitis with a mild cough where the cough seems associated with postnasal drip and there is no significant fever.

Sadly these grey areas will always be a problem but this will be eased when a fully functioning testing system means we don’t feel pressure to ration them.

Pulse October survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens