‘When you hear hoofbeats, think of horses not zebras.’ The old adage is well known to GPs but what should you do on the rare occasion that you’re faced with a zebra and not a horse? Get up to date on identifying rare diseases with our new series on spotting unusual conditions in the surgery.

What is retinoblastoma?

Retinoblastoma is the most common intraocular tumour in children.

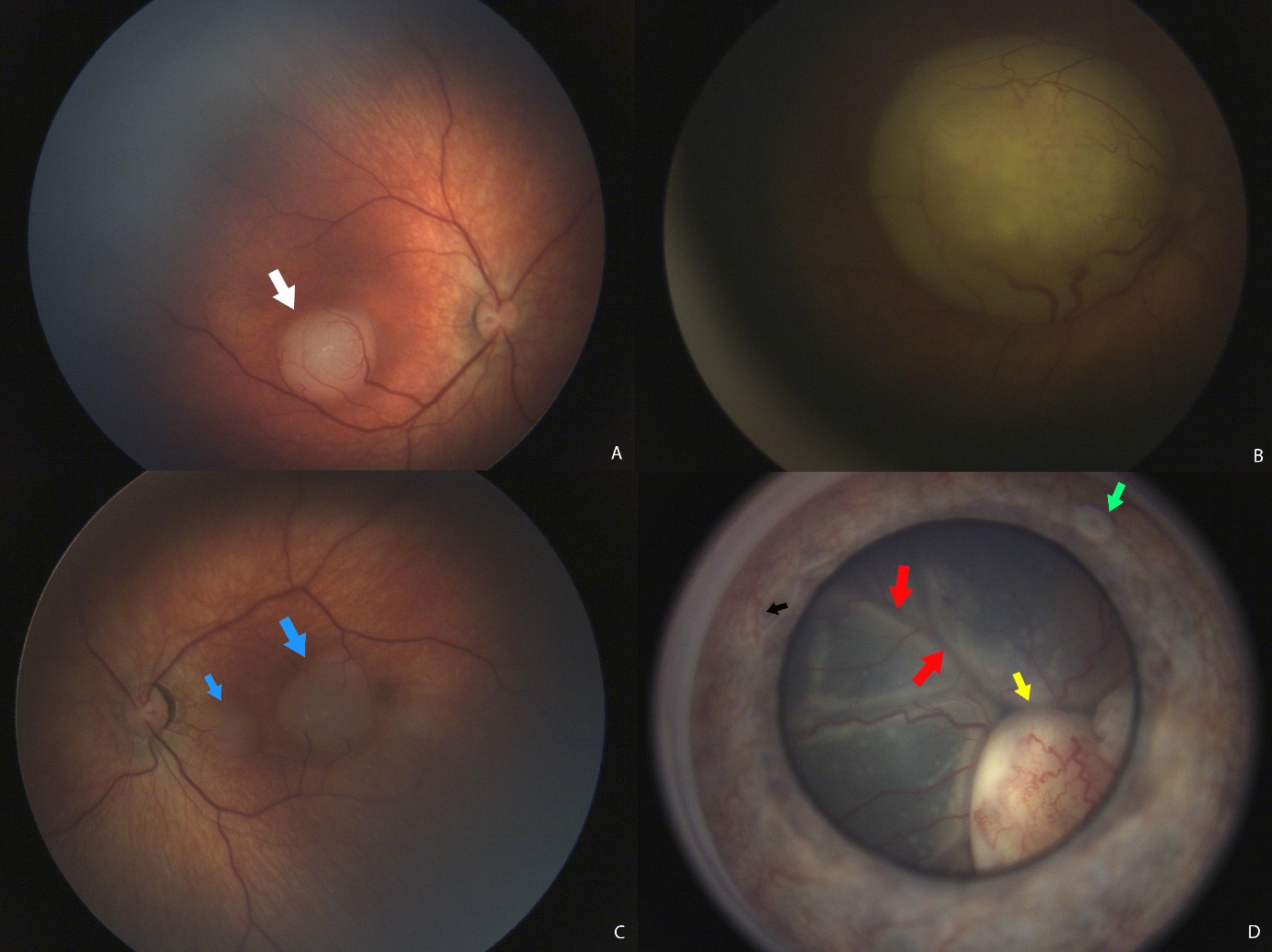

Figure 1 Example of some tumour presentations : (A) a small unilateral tumour just under the fovea (white arrow). (B) a large tumour that is obscuring the whole macula (C) a patient with familial retinoblastoma with multifocal tumours (blue arrows) (D) an advanced tumour (yellow arrow) with a retinal detachment (red arrows), iris tumour seeds (green arrow) and iris neovascularisation (black arrow).

It is a tumour initiated by genetic changes in susceptible developing retinal cells during infancy which is why it is seen predominantly in children under the ages of five. Research in to retinoblastoma genetics have paved the way for the understanding of genetics and cancer as a whole1.

Two centres in the UK (the Royal London Hospital and Birmingham Children’s Hospital) treat all retinoblastoma patients and their families. Treatment is complex and includes chemotherapy, focal ocular treatment, and enucleation (removal of the eye).

Prevalence

Retinoblastoma is rare. There are no gender or racial predilections and it makes up about 3% of all childhood cancer cases. Even for ophthalmologists, it can be a disease seen only once or twice in their careers. It occurs in about one in 20,000 live births and there are a total of approximately 40-60 new cases each year in the UK. Worldwide, there are about 8,000 new cases each year and unfortunately, 40 to 50% of cases in Asia or Africa still die from the disease. In comparison, countries like the UK, USA, Japan and Canada have survival rates that are close to 100%. This fact highlights the importance of early detection and prompt referral to specialist centres.

Retinoblastoma is a very treatable (even curable) cancer and this is what makes it such an important zebra to spot!

Presentation

There are two kinds of retinoblastoma: heritable retinoblastoma (45%) and non-heritable retinoblastoma (55%). Retinoblastoma occurs due to a mutation on the Rb1 gene on chromosome 13, which acts as a tumour suppressor gene. Generally, if a tumour is bilateral or there is a family history, then it is the heritable form (inherited as an autosomal dominant trait).

A unilateral tumour that occurs sporadically in older children tends to suggest that it is the non-heritable form. However, we now know that up to 15% of unilateral retinoblastoma patients actually have the heritable form. A family history of retinoblastoma or having eyes removed for an unknown cause at a young age are potential clues.

The heritable form is picked up around nine months of age whereas the non-heritable forms are picked up on average around 24 months of age.

The key feature is a white reflex, also known as leukocoria2.

This symptom is found in 50-70% of all patients presenting with retinoblastoma. In the UK, a red reflex test is done at birth and during the six week check. If the tumour has developed early or in utero, it could be picked up at the six week check. However, because retinoblastoma can develop in the first few years of life, the red reflex test is pertinent at any age if there is a suspicion of a white reflex seen by the parents. It should be part of a GP’s skillset to examine a child of any age with any eye condition.

In a study on lag time for retinoblastoma in the UK, close to 80% of leukocoria2 were spotted initially by the parents themselves. It is possible to see a white reflex with the naked eye but by far the most common modality is via flash photography. A common reason for a leukocoria in photographs is because the light is reflected off the nasally situated optic disc. The red reflex test, when performed in these cases, however, is usually normal. A constant asymmetric, dull, white reflex is a cause for concern. Although many cases will be false positives3, it is difficult for GPs to reassure parents unless they examine the entire fundus. As a result, it is essential they refer to a local paediatric ophthalmology service urgently if they are unsure.

Strabismus, otherwise known as a squint, or a misalignment of the eyes is the second most important associated feature. It is found in 20-25% of patients with Rb. In late stages of disease, buphthalmos (an abnormally enlarged eye), proptosis (a bulging eye), uveitis (inflammation of the eye), and orbital cellulitis are possible symptoms. They represent high pressure within the eye or extraocular extension of the tumour, so are not favourable signs to see.

Without treatment, the tumour invades locally and metastasises, causing death within two years. In rare cases, the tumour does not become a full-blown retinoblastoma and remains inert as a retinoma.

In 3-5% of patients with heritable retinoblastoma, there is a chance of developing a tumour in the pineal gland. This is called trilateral retinoblastoma.

Ocular oncologists commonly use the international intraocular retinoblastoma classification (IIRC), which stages the tumours from grades A to E (in order of best to worst prognosis).

Examination

What adds to the difficulty in community practice is that retinoblastoma occurs in an age group where examination is not straightforward, especially in a structure like the retina, which is elusive at the best of times.

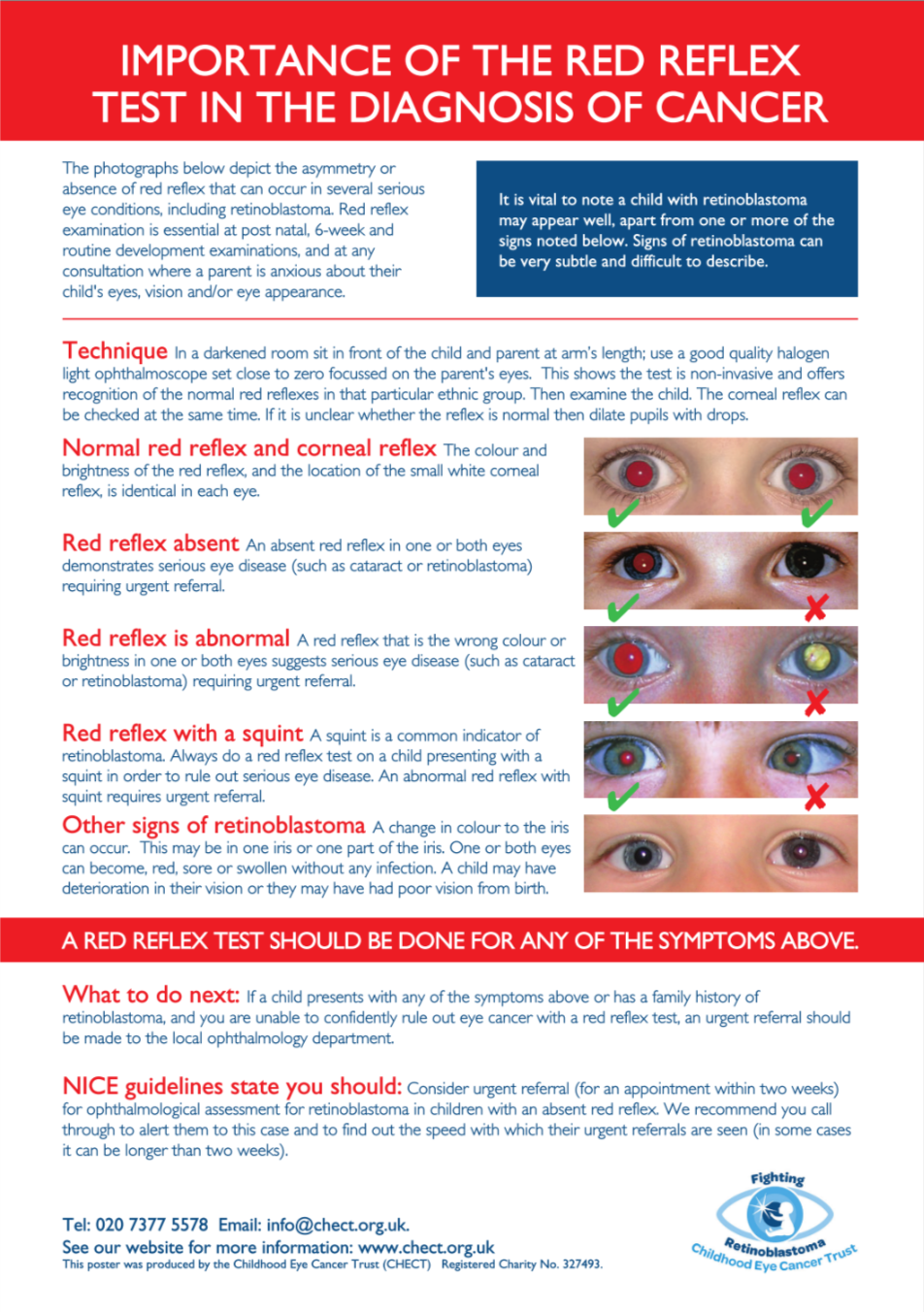

However, the red reflex test is still a very useful screening test for retinoblastoma as it is fast, easy, cheap and non-invasive. A red reflex is a reflection of the normal healthy fundus. It is naturally darker and more difficult to see in black and minority ethnic (BME) individuals and lighter in whites. In darker individuals, the reflexes often appear dull or yellowish-white rather than orange. The most appropriate method is to examine the parents initially before examining the child – this allows for two things:

- If old enough, the child will see that the procedure is non-invasive and be less averse to being examined.

- By visualising the red reflex in the parents, the clinician can recognise the quality of a normal red reflex for that particular ethnic group. Despite a duller reflex, it should still be symmetrical and similar to that of the parents.

Red reflex test: kindly provided by www.chect.org.uk. Click image to download chart.

Apart from leukocoria and strabismus, iris heterochromia (change in colour of the iris) is also a common presenting symptom and was the first sign that prompted the family to seek help in 13% of families.

Other causes of leukocoria include cataracts, Coats’ disease (abnormal vascular growth in the retina), persistent fetal vasculature and retinal detachments, all of which should still prompt urgent referrals.

The relevance of family history

If a patient has heritable retinoblastoma, it means that there is a risk to their future children or their siblings. Retinoblastoma families are usually kept in close contact by the retinoblastoma centres, as decisions must be made on the risk of future or existing young family members developing the tumour. If they are deemed to be at higher risk than the general population, they remain under specialist care until they either reach a certain age or have their genetic risk profile confirmed.

If a GP has a patient with previous retinoblastoma, it is important to ask if they are aware of the potential heritable risks. In the last two decades the understanding of retinoblastoma genetics has improved significantly, so a referral to a geneticist is appropriate for survivors who are now of childbearing age. Most patients would have sought out the relevant information via the retinoblastoma centres themselves. If for some reason they are completely unaware that it carries a risk to their future children, forward them to any of the additional resources below or refer them to a geneticist for counselling. It is important to know that not all retinoblastoma is heritable, but this risk must be stratified based on relevant clinical information and genetic testing.

Secondly, another important feature of heritable retinoblastoma is that these patients have an increased risk of secondary tumours not just in the eye but elsewhere, as the Rb1 gene is present in every cell of the body. Researchers have found that giving radiotherapy (this was more common a generation ago) has led to an increased incidence of soft tissue tumours in the head and neck. An adult with treated retinoblastoma who develops unusual lumps or bumps anywhere else should be referred for an oncology workup.

Due to this lifetime risk, patients with heritable retinoblastoma should avoid oncogenic factors like smoking, UV overexposure, and radiation. A high radiation test like a CT scan should only be requested for these patients when the clinical need is significant, otherwise an MRI scan is a better option.

Referral

If you see leukocoria in a child or see features suspicious of retinoblastoma, then the child should be referred to the closest paediatric ophthalmologist. All referrals should be marked as urgent, especially if a white reflex is seen in a child under the age of five.

An optometrist can be helpful to assist with examining the fundus, but not all optometrist practices see babies and small children.

If you require information about family counselling, non-urgent queries, advice on referral pathways, or if you are having difficulties with your referrals, feel free to contact the resources below for useful support.

Dr Damien CM Yeo is a clinical fellow in paediatric ophthalmology and strabismus and Mr M. Ashwin Reddy is a consultant paediatric ophthalmologist and retinoblastoma surgeon, both at the department of ophthalmology at the Royal London Hospital.

References:

- Fabian ID, Onadim Z, Karaa E et al. The management of retinoblastoma. Oncogene. 2018 Mar;37(12):1551-1560. doi: 10.1038/s41388-017-0050-x

- Posner M, Jaulim A, Vasalaki M et al. Lag time for retinoblastoma in the UK revisited: a retrospective analysis. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015625. Doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015625

- Muen WJ, Hindocha M, Reddy MA. The role of education in the promotion of red reflex assessments. J R Soc Med Sh Rep 2010;1:46. Doi:10.1258/shorts.2010.010036

Additional resources

Childhood Eye Cancer Trust

- 02073775578

- [email protected]

- www.chect.org.uk/gp

Royal London Hospital retinoblastoma service

- https://www.bartshealth.nhs.uk/retinoblastoma

- 020 35941419

Birmingham Children’s Hospital retinoblastoma service

- 0121 333 9475

The above photographs were kindly provided by CHECT with parental consent.

Pulse July survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens