Cardiovascular clinic: Pericarditis

A 35-year-old man presents with sudden onset sharp chest pain following a flu-like illness. The pain does not radiate and is not associated with breathlessness. It is relieved slightly by sitting up and leaning forwards. He has no past medical history of note. His temperature is 36.3° and on auscultation there is a quiet pericardial friction rub at the end of expiration, at the left lower sternal border. His GP suspects pericarditis and refers him to A&E.

The problem

Pericarditis involves inflammation of the pericardium. The pericardium has two layers and if blood or other fluid leaks between them, inflammation can occur.

The cause is unknown in most cases, but it can be caused by several viruses, including Covid-19, or be secondary to pneumonia, cancer or renal failure, or could also follow a heart attack (Dressler’s syndrome) or chemoradiotherapy. Sometimes more chronic symptoms can be associated with connective tissue disorders or autoimmune disease, including lupus, rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis, in which case the pain is often not as sharp.

Features

Patients tend to present acutely with chest pain after flu-like symptoms such as fever and myalgia. Pericardial pain is often sharp or stabbing and worse on inspiration, swallowing and lying flat. The pain can be improved by leaning forwards. It can sometimes radiate to the neck, left shoulder or down the arm. There may be breathlessness.

Diagnosis

To diagnose pericarditis, a thorough history is helpful and features such as a preceding cough, fever, flu-like symptoms or GI upset can provide vital clues. Clearly, it is not unreasonable to think of Covid-19 as a cause.

Past medical history could include previous chemo or radiotherapy, autoimmune conditions, renal failure, recent myocardial infarction, and any previous episodes of pericarditis (as recurrence is not unlikely).

A pericardial friction rub might be heard at the end of expiration. To give yourself the best chance of hearing this, have the patient lying on their left side with their head resting on their left arm, or sitting forward.

Red flags include muffled heart sounds, elevated jugular venous pressure and peripheral oedema. Features of cardiac tamponade, which is a medical emergency because of fluid accumulation within the pericardium, include hypotension and tachycardia.

Routine investigations

ECG

The ECG is abnormal in 80% of patients with acute pericarditis and can be performed by the GP. If normal, pericarditis would be very unlikely.

Findings can include widespread PR depression and diffuse ST ‘saddle-shaped’ elevation. In later stages, generalised T-wave inversion may be observed.

Chest X-ray

This is used to rule out a pericardial effusion (cardiomegaly) and abnormalities in the mediastinum or lung fields, such as lung malignancy or pneumothorax.

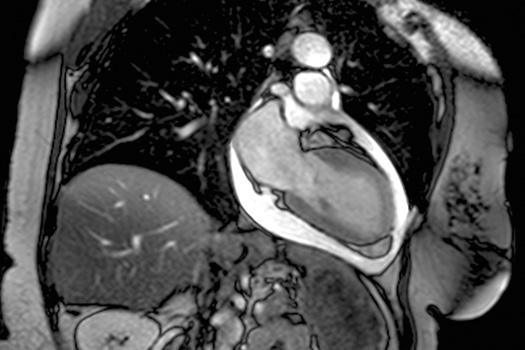

Echocardiogram

An echocardiogram can identify thickening of the pericardium and assess the ventricular function and the presence of a pericardial effusion. An effusion of greater than 1.5cm in width is significant as it can precipitate collapse of the right ventricle during diastole, leading to reduced ventricular filling and subsequent haemodynamic compromise. This is cardiac tamponade. Signs include hypotension, distended neck veins (elevated JVP) and muffled heart sounds.

Blood tests

Bloods may reveal elevation in inflammatory markers (CRP and ESR) along with a troponin rise (as inflammation of the epicardium can lead to troponin release) and creatine kinase. A, FBC may reveal an elevated white cell count. Throat and nose swab for Covid-19 PCR can be performed.

Management

In many cases, the GP can manage this without referral to hospital, though some GPs might not feel confident about this. If the ECG is typical and there is a pericardial rub, the patient is unlikely to be suffering from any serious complications. If however, there is any evidence of reduced cardiac output and the heart sounds have become quiet, with no rub, the patient should be referred for urgent assessment in case of pericardial effusion. Most cases of recurrent pericarditis are less acute and can be managed in primary care, sometimes with guidance from the cardiac centre.

Treatments for pericarditis depend on the cause and may include:1

• Anti-inflammatory medication, such as ibuprofen, aspirin, naproxen or indomethacin.

• Prednisone.

• Analgesia.

• Colchicine as a combination therapy with the above. It is particularly useful for those with recurrent pericarditis, where azathioprine and IV immunoglobulin may also be considered.

• Surgery can be necessary in some cases (a ‘pericardial window’ procedure) to form a connection between the pericardial space and the pleural cavity. This allows a pericardial effusion to drain from around the heart.

Dr Louise Tulloh is a GP in Bristol. Professor Robert Tulloh is a professor of congenital cardiology and pulmonary hypertension at the Bristol Heart Institute

References

1 Adler Y et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. European Heart Journal 2015 doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv318

2 Liberman M et al. Ten-Year Surgical Experience With Nontraumatic Pericardial Effusions. Arch Surg 2005;140:191-5. doi:10.1001/archsurg.140.2.191

Pulse July survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens

Visit Pulse Reference for details on 140 symptoms, including easily searchable symptoms and categories, offering you a free platform to check symptoms and receive potential diagnoses during consultations.

Related Articles

READERS' COMMENTS [2]

Please note, only GPs are permitted to add comments to articles

I can’t imagine any GP thinking pericarditis can (or should) be managed in primary care.

Sorry pressed send too early: Nor should they. GPs do not have access to same day CXR, some do not have ECGs, and no one in their right mind is going to see ST elevation on an ECG and say ‘ah yes, this is pericarditis, let’s just manage this in primary care’ and not refer to hospital

At least, not if they want to avoid a GMC hearing for the inevitable missed STEMI.

Sorry, article is informative but the suggestions of how to manage In primary care alone are completely unrealistic in today’s litigious world.