Standard current treatment

All patients with a diagnosis of angina should be provided with a sublingual nitrate for treatment of acute symptoms.

Glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) is available as a 300µg tablet or 400µg spray, and can be used to relieve acute symptoms or prophylactically prior to exercise.

Patient education is vital to ensure appropriate use. Advice should include how to recognise symptoms, correct dosing and the method of administration. Patients should be advised on precautions to avoid hypotensive complications, and be reminded they can repeat the dose in five minutes if symptoms persist, but should seek medical help if there is then no response.

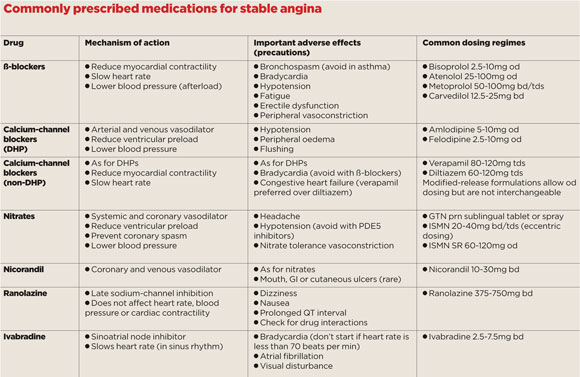

In most cases, it is worthwhile also to prescribe an oral drug that reduces the frequency of angina. There are a number of medications available for stable angina, and little evidence to suggest any single agent is more effective than another.1 It is worth adopting a stepwise approach and, in the absence of contraindications or drug intolerance, most guidelines recommend starting with a ß-blocker or calcium-channel blocker (see table).2

First-line agents

ß-blockers reduce heart rate and myocardial contractility, thereby reducing oxygen demand. They are recommended in all patients with a history of myocardial infarction or impaired left ventricular function, where they have been demonstrated to improve survival. Important adverse effects include fatigue, bradycardia, hypotension and erectile dysfunction. Because of the potential for bronchospasm, they are contraindicated in asthma but can be cautiously introduced in COPD. Commonly prescribed examples include bisoprolol (2.5 to 10mg daily), atenolol (25 to 50mg twice daily), metoprolol (50 to 100mg two to three times daily), or carvedilol (12.5 to 25mg twice daily).

Calcium-channel blockers have a number of effects, including coronary and peripheral vasodilatation. They are useful for patients who do not tolerate or have contraindications to ß-blockers and achieve similar improvements in angina severity. The non-dihydropyridine agents, including verapamil (80 to 120mg tds) and diltiazem (60 to 120mg tds), also reduce heart rate and myocardial contractility, and should be avoided in patients taking ß-blockers or with impaired ventricular function. Diltiazem is available in a wide variety of modified-release formulations, and it is important to note that these have differing pharmacokinetic profiles and are not interchangeable, so prescribers should specify the brand.

Long-acting dihydropyridines, including amlodipine (5 to 10mg daily) and felodipine (2.5 to 10mg daily), do not affect heart rate or ventricular function, and can be safely used either alone or with a ß-blocker.

Add-on treatment

If the initial drug is not tolerated, or fails to adequately control symptoms, an additional medication should be added.

Long-acting nitrates can be administered in oral or transdermal preparations. They induce systemic and coronary vasodilatation and are most effective in combination with one of the first-line agents. Isosorbide mononitrate (ISMN) is available as a conventional formulation, taken at a dosage of 20 to 40mg two to three times daily, or in a number of modified release preparations, at a dosage of 40 to 120mg once daily. In order to avoid the development of nitrate tolerance, ISMN should be prescribed in an eccentric manner – with repeat doses taken over a six to 10-hour period – allowing a nitrate-free interval. It is important to advise male patients prescribed ISMN or GTN to avoid taking PDE5 inhibitors within 24 hours of use, because of the risk of severe hypotension.

Nicorandil, at 10 to 30mg twice daily, is another vasodilator that improves coronary perfusion due to a combination of potassium channel opening and a nitrate effect. As a result, nicorandil, like ISMN, is associated with headaches and is contraindicated in combination with PDE5 inhibitors.

One uncommon but well-recognised adverse effect is the development of ulcers that can affect the oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, or skin.

What’s newly available?

Ranolazine, prescribed at 375 to 750mg twice daily, inhibits the late-opening sodium channel and has been demonstrated to improve angina symptoms as monotherapy, or, in combination with first-line agents.3-5 It has no significant haemodynamic effects, making it useful for treating patients with hypotension or cardiac conduction disturbances, who may not tolerate ß-blockers or calcium-channel blockers. It undergoes hepatic metabolism, mainly via CYP3A4, and should be avoided in patients taking potent inhibitors of this enzyme, such as verapamil and diltiazem. It should not be taken by individuals with significant renal dysfunction, such as an eGFR at less than 30ml/min, or those with QT interval prolongation.

Ivabradine acts on the sinoatrial node to lower heart rate in patients in sinus rhythm, but not atrial fibrillation. Unlike ß-blockers, it has no significant effect on blood pressure or myocardial contractility. It has been shown to reduce angina frequency and severity either alone or in combination with a ß-blocker,6,7 and appears to improve outcomes in patients with symptomatic systolic heart failure and a resting heart rate of over 70 beats per minute.8

The recently reported SIGNIFY trial,9 however, demonstrated no improvement in outcomes in stable coronary artery disease without heart failure. A recent meta-analysis has also reported an increase in the incidence of atrial fibrillation.10 In response to these observations, the MHRA recommended prescribers avoid concomitant use of potent CYP3A4 inhibitors (non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers) and start treatment at 5mg bd to minimise the risk of bradycardia.

Atypical cases and tailored treatment

While the predominant cause of angina is atherosclerotic obstruction of the epicardial coronary arteries, it is possible to develop symptoms without a significant stenosis.

Prinzmetal, or vasospastic angina, occurs in response to transient coronary arterial spasm, and typically manifests at rest, particularly in the early hours of the morning. Acute symptoms respond to GTN and smoking cessation should be strongly encouraged as this appears to reduce the frequency of episodes. In contrast to classical angina it is usually recommended to avoid ß-blockers as these may exacerbate vasospasm.11 Calcium-channel blockers and nitrates remain effective.

Cardiac syndrome X is a condition where patients experience exertional chest discomfort, often with non-invasive evidence of inducible myocardial ischaemia, in the absence of obstructive or vasospastic coronary artery disease. The cause is uncertain and diagnostic criteria vary. It has a good prognosis, and patient reassurance is important. If symptoms remain troublesome or require frequent use of GTN, it can be treated as for classical angina.

Non-drug options and their evidence

Although interventional treatments for stable angina have not, in the absence of specific high-risk features, demonstrated prognostic benefits, they clearly have a role in improving symptoms refractory to pharmacological approaches.12,13

Most patients with refractory angina on a combination of two agents should be referred for the consideration of coronary revascularisation, and additional medications should only be prescribed if this is not suitable.

The most common approach is percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), where vascular stents are deployed to relieve obstruction and improve arterial flow.

These are typically outpatient procedures, and symptomatic response is immediate. In appropriately selected patients, the PCI-related risk is very small, and the current generation of drug-eluting stents have low rates of restenosis.

Coronary artery bypass grafting can offer similar symptomatic gains in individuals with more complex anatomical features, albeit with a longer recovery time. In some patients, particularly those with diabetes, it may offer improved long-term outcomes compared with PCI.

Key points

• There is little evidence on effectiveness to guide choice of antianginals, but ß-blockers are recommended in all patients with a history of MI or impaired LVF

• Avoid non-dihydropyridine calcium-channel blockers in patients taking ß-blockers, or with or impaired LVF

• Allow a nitrate-free interval to avoid nitrate tolerance

• Newer antianginals include ranolazine and ivabradine

Professor Nick Mills is professor of cardiology and a consultant cardiologist at the University of Edinburgh and the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh

Dr Philip Adamson is a clinical research fellow in cardiology at the University of Edinburgh

References

1 Belsey J, Savelieva I, Mugelli A et al. Relative efficacy of antianginal drugs used as add-on therapy in patients with stable angina: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2015;22:837-48.

2 Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the Task Force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. European Heart Journal 2013;34:2949-3003.

3 Stone PH, Gratsiansky NA, Blokhin A et al. Antianginal efficacy of ranolazine when added to treatment with amlodipine: the ERICA (Efficacy of Ranolazine in Chronic Angina) trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2006;48:566-75.

4 Chaitman BR, Pepine CJ, Parker JO et al. Effects of ranolazine with atenolol, amlodipine, or diltiazem on exercise tolerance and angina frequency in patients with severe chronic angina: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;291:309-16.

5 Chaitman BR, Skettino SL, Parker JO et al. Anti-ischemic effects and long-term survival during ranolazine monotherapy in patients with chronic severe angina. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2004;43:1375-82.

6 Tardif JC, Ford I, Investigators I et al. Efficacy of ivabradine, a new selective I(f) inhibitor, compared with atenolol in patients with chronic stable angina. European Heart Journal 2005;26:2529-36.

7 Tardif JC, Ponikowski P, Kahan T et al. Efficacy of the I(f) current inhibitor ivabradine in patients with chronic stable angina receiving beta-blocker therapy: a 4-month, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. European Heart Journal 2009;30:540-8.

8 Swedberg K, Komajda M, Böhm M et al. Ivabradine and outcomes in chronic heart failure (SHIFT): a randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet 2010;376:875-85.

9 Fox K, Ford I, Steg PG et al. Ivabradine in stable coronary artery disease without clinical heart failure. NEJM 2014;371:1091-9.

10 Martin RI, Pogoryelova O, Koref MS et al. Atrial fibrillation associated with ivabradine treatment: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Heart 2014;100:1506-10.

11 Robertson RM, Wood AJ, Vaughn WK et al. Exacerbation of vasotonic angina pectoris by propranolol. Circulation 1982;65:281-5.

12 Boden WE, O’Rourke RA, Teo KK et al. Optimal Medical Therapy with or without PCI for Stable Coronary Disease. NEJM 2007;356:1503-16.

13 Frye RL, August P, Brooks MM et al. A randomized trial of therapies for type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease. NEJM 2009;360:2503-15.

14 Verheye S, Jolicoeur EM, Behan MW et al. Efficacy of a device to narrow the coronary sinus in refractory angina. NEJM 2015;372:519-27.

Pulse October survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens