In the first of our Masterclass series, Dr Peter Bagshaw explains the key points in understanding, diagnosing and managing dementia in general practice. This series showcases content from our Pulse Reference site, which supports GPs in making diagnoses. We will be expanding this service to include advice on managing and treating conditions

Accepted definition of the condition/diagnostic criteria

Dementia is a term used to describe a range of cognitive and behavioural symptoms that can include memory loss, problems with reasoning and communication, a change in personality, and a reduction in a person’s ability to carry out daily activities. Dementia is a progressive neurodegenerative disease.

Impairment that is not sufficiently severe to interfere in activities of daily living is labelled mild cognitive impairment.

Epidemiology

There are currently around 900,000 people with dementia in the UK, projected to rise to 1.6 million people by 2040 due to changing demographics. Increasing age is the main risk factor, but 12 other factors have been identified – less education, hypertension, hearing impairment, smoking, obesity, depression, physical inactivity, diabetes, infrequent social contact, excessive alcohol consumption, head injury and air pollution. It has been estimated that addressing reversible risk factors could reduce the risk of dementia by 40%.

Nearly all cases of dementia are the result of a complex disease. In these cases, genes may increase the risk of developing dementia, but they don’t cause it directly. In some rare cases, dementia is caused directly by a single-gene disease.

Diagnosis

There is no single test for dementia, and memory loss alone is not sufficient to make the diagnosis. Assessment should include a validated brief structured cognitive instrument, blood tests to rule out reversible causes of cognitive decline, and, in some cases, brain imaging. Although a full assessment should generally be carried out by the local memory assessment service, it may be appropriate for the diagnosis to be made in primary care if the patient is very frail and has advanced dementia using the DiADeM tool.

Clinical features are variable, and may be difficult to spot as they occur insidiously over time. They may include memory loss, problems with reasoning and communication, difficulty making decisions or carrying out coordinated movements, apathy or agitation and impairment of executive function.

The main types of dementia include:

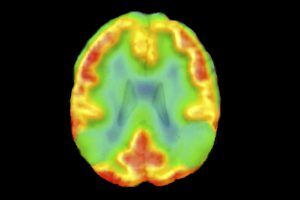

- Alzheimer’s disease (60% of total), where memory loss is usually the first presenting symptom; it is associated with a build-up of amyloid and tau proteins in the brain, and cortical atrophy is the typical finding on imaging.

- Vascular dementia is the second commonest, sometimes occurring as a stepwise deterioration, but often clinically indistinguishable from Alzheimer’s. White matter changes and cortical infarcts are the classic imaging findings, but there is an overlap with normal ageing changes, and around 10% of dementia is classified as ‘mixed’.

- Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) accounts for around 5% of the total, often associated the Parkinson’s disease and presenting with hallucinations more commonly than other dementias, and imaging generally shows preservation of the medial temporal lobes when compared with Alzheimer’s.

- Frontotemporal dementia classically presents with behavioural changes such as disinhibition, although aphasic and semantic variants occur: memory loss tends to be a late feature, so it is worth considering when a patient presents with odd behaviour or language difficulties

The main differential diagnoses include delirium if the history is shorter, depression which can often give cognitive and memory issues, B12 or thiamine deficiency and hypothyroidism. Most of these will show on screening blood tests, but a therapeutic trial of antidepressants may sometimes be appropriate.

Treatment

Although prevention is possible as discussed above, there is currently no cure for dementia. Control of preventable risk factors may slow deterioration, including such simple things as advising hearing aids for deafness. At the time of writing (December 2023) two drugs which reduce protein build-up (lecanemab and donanemab) have been shown to slow progression in Alzheimer’s by a modest amount (25-33%) but have yet to be licensed in the UK.

The current drugs available include AChEIs such as donepezil, licensed for mild to moderate Alzheimer’s, and Memantine licensed for moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s. Although unlicensed, ACHeIs can also be of benefit in DLB. None slow the rate of progression, but can improve symptoms of memory loss and apathy. All are relatively safe, though the AChEIs commonly give nausea when first started, and can also cause heart block more rarely. It is important to review medication and stop drugs such as sedatives or anticholinergics which can worsen dementia.

Non-drug interventions such as cognitive stimulation therapy should be offered to everyone with a new diagnosis of dementia, and group reminiscence therapy and cognitive rehabilitation can also be useful in preserving function. As dementia is progressive, and may involve losing capacity at some stage, it is important to raise sensitively issues around planning for the future such as wills, lasting powers of attorney, treatment escalation plans and discussions around DNACPR. Driving is often a major concern, and GPs should advise patients that they have a legal duty to inform the DVLA and their insurance company that they have dementia. We should only contact DVLA directly if they fail to do so, and we believe a patient’s impairment leaves others exposed to a risk of death or serious harm.

The positive support available, whether via support workers, memory cafes or singing for the brain, should be stressed with the aim of ‘living well with dementia’. It is of course vital to involve and offer support to carers, and ensure they know where to turn when the condition worsens.

Prognosis

Dementia is a life-limiting condition. There is progressive deterioration that can be considered as three stages, although the rate of deterioration varies between individuals:

- Early stage (mild) — years 1–2. This stage may be overlooked. Onset is gradual, and features include becoming forgetful, communication difficulty, losing track of time, difficulty making decisions.

- Middle stage (moderate) — years 2–5. Limitations become clearer and more restricting. Features include becoming very forgetful, increasing communication difficulty, help needed with personal care, unable to prepare food, behaviour changes.

- Late stage (severe) — year 5 and later. Near-total dependence and inactivity. Features include very serious memory disturbances, more obvious physical features, unaware of time or place, difficulty understanding what is happening around them, unable to recognize relatives and friends, unable to eat without assistance.

There is considerable variation in the time from presentation to death: people diagnosed in their late 60s to early 70s have a median lifespan of 7–10 years, but this is reduced to three years for people diagnosed in their 90s.

Dr Peter Bagshaw is a GP and clinical lead for dementia at Somerset ICB

Sources and further reading

NICE. Dementia: assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers. NG97. 2018

Alzheimer’s Society website

NHS England. Dementia diagnosis and management: A brief pragmatic resource for general practitioners. 2015

Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A. Dementia prevention, intervention and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020;396:413-446

Pulse October survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens