Top tips for GPs in palliative care

In the latest in our Pulse Live series, where experts summarise their presentations from Pulse Live events, Dr Nicolas Alexander, GP and GP trainer with an interest in palliative care, provides some practical tips on managing palliative care in general practice

Death is an area clinicians may feel uncomfortable with and find challenging. However, we can make a tangible difference in palliative care and this needn’t be onerous with the right tools. Palliative care is not the same as end-of-life care. It may start from diagnosis, when symptoms develop, or when a patient is deteriorating.

Palliative care is not just something to consider in cases of cancer, but can also be appropriate for conditions including heart failure, COPD, dementia, liver cirrhosis and general frailty.

Identifying those who are in the palliative phase of an illness allows patients a modicum of control, allowing them to express wishes, outline priorities and set goals. It allows a better chance of a ‘good death’ on the patient’s terms. It aims to avoid the patient dying in hospital unexpectedly or unnecessarily.

In this article we consider:

- how to identify patients who are appropriate for palliative care

- how to have difficult conversations

- how to manage symptoms and prescribing, including at end of life

- how to identify when a patient is dying

- when to involve the palliative care team.

How to identify palliative patients

The simplest test is the surprise question – ‘Would you be surprised if this patient died in the next year?’ If the answer is no, a palliative approach would be appropriate. If there is uncertainty, functional and disease-specific indicators should be examined.

Functional indicators that a palliative approach should be considered include:

- Patient is dependent on others for all their care, spending most of the day in a chair or bed, or deteriorating with no reversibility.

- Patient is physically frail in appearance, low in BMI or muscle mass, or has lost more than 10% body weight. These factors are indicative of low physiological reserve.

- Recurrent crises needing treatment including hospitalisations which are unplanned, increasing in frequency or with increasing functional deterioration.

Disease specific indicators to be aware of include:

- Advanced and unstable disease with a complex symptom burden

- Decreasing response to treatment or decreasing reversibility of the condition

- Ongoing symptoms despite maximal therapy (e.g. breathless at rest or on minimal exertion in COPD)

- Advanced disease with no prospect of curative treatment or where treatment is for symptom control or palliation.

The Supportive and Palliative Care Indicative Tool offers a one-page summary that is helpful to have on hand and has some more specific examples.

How to start difficult conversations

Important factors to discuss include discussing the prognosis, resuscitation status, escalation and advanced care planning, and preferred place of care and death. These conversations take time, sensitivity and planning, and patients vary. Some may already have had thoughts but been unsure how to bring them up, others may not be ready to think about this. It is important these conversations are offered and not forced.

Invite the patient in proactively, invite them to bring any family or friends whom they would like to be involved, and allow plenty of time for this. Often decisions won’t be made in the first consultation and may take a few visits. These are often ongoing conversations and best approached with patience, aiming for these decisions to be made proactively rather than in extremis when things may be more difficult and emotionally charged.

It is often helpful to frame this as a shift from aiming to prolong life to making the most of the time we have, however long it may be. These conversations require trust and continuity with one GP can be helpful. This allows a consistency of message, allows trust to be built if they do not know any clinician particularly well, and hopefully prevents too much repetition.

How to manage symptoms and prescribing

Deprescribing is important and often worth starting early. This is especially important in older patients who may be on multiple medications which offer limited benefit to them, such as statins, antihypertensives, antiplatelets, and dietary supplements.

Common symptoms that need treating in palliative care include pain, gastrointestinal symptoms (colic, diarrhoea or constipation, nausea and vomiting), respiratory symptoms (shortness of breath, excess respiratory secretions), and agitation or distress.

Pain control is important and we should be less wary of opiates in these patients. However it is important we remember the analgesic pain ladder and start with simple paracetamol or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication before introducing opiates, and starting with low dose codeine, dihydrocodeine or tramadol before escalating to other opiates – which will mostly be morphine (or oxycodone in the case of reduced renal function).

Different opiates have different potencies, and it is important to avoid being on multiple different opiates (eg codeine and morphine) so aim to convert all regular opiates to one long-acting formulation, whether that is oral (eg. morphine sulphate modified release), topical (buprenorphine or fentanyl patches) or subcutaneous (e.g. a syringe driver). Remember to add breakthrough analgesia for when pain flares – this is generally at one-sixth of the dose of the total 24-hour analgesia.

Other pain types can occur and are often approached differently – neuropathic pain (tricyclic antidepressants, gabapentin, pregabalin), abdominal colic (hyoscine butylbromide 10-20mg QDS, glycopyrronium 200-600mcg QDS). Dexamethasone has some utility in specific types of pain (eg, raised intracranial pressure, liver capsule pain) but this should always be under specialist guidance.

Nausea and vomiting is common and can be a side effect of medication or of the disease process. Management options include cyclizine (50mg TDS) and metoclopramide (10-20mg TDS), which is commonly used in primary care. Some less often used and with utility if there is distress and agitation also present – haloperidol (0.5-1.5mg TDS) and levomepromazine (6.25 to 25mg QDS).

Constipation is also common and our options include macrogols, lactulose, senna, docusate, but we need to exercise caution. Macrogols need a certain water intake to be effective. Lactulose can cause colic and abdominal cramps. Senna and bisacodyl can reduce stool transit time and we need to be cautious in abdominal pathology and the risk of bowel obstruction.

Anxiety and agitation are common symptoms and lorazepam (0.5-1mg BD orally) works well for this. An alternative is midazolam (2.5-5mg) which can be given subcutaneously or in a syringe driver.

Excess respiratory secretions are common towards the end of life, and can be treated with glycopyrronium (200-600cmg QDS) or hyoscine hydrobromide (400mcg QDS).

Prescribing in end of life

Prescribing medication for the terminal phase of illness can be done at any time, but ensure that it’s in place if the patient is unstable or deteriorating. Think about who will be administering the medications (this varies by area but often will be the district nursing team). Ensure water for injection (which the medications will be diluted in) has also been prescribed. Remember opiates should be written in words and figures and in many areas, there will also be a MAR (Medications Administration Record) chart to be filled in to allow the PRN (‘as needed’) medication to be given. It is often helpful to have a range for doses which will allow some flexibility if and when things progress.

This is an example of prescriptions for end-of-life:

- Pain – Morphine (1.25mg to 2.5mg SC) or oxycodone (1.25mg to 2.5mg SC) immediate release 1-hourly.

- Anti-emetic – Haloperidol 0.5-1.5mg TDS SC.

- Agitation – Midazolam 2.5-5mg SC 1-hourly max 25mg.

- Secretions – Glycopyrronium 200mcg TDS SC.

- Dilutant – Water for injection 10ml (x10 vials)

How to identify deterioration and the dying patient

Different patients and different illnesses will progress differently.

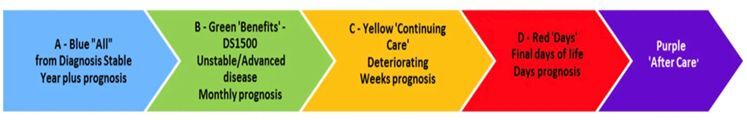

The Gold Standard Framework Traffic Light system is a helpful way to consider the palliative care phases:

Blue: life limiting diagnosis but relatively symptom free.

Green: some palliative symptoms starting, functionally declining slowly but overall managing OK

Amber: worsening symptoms despite treatment, things changing more rapidly, functional decline and patient a lot more limited (eg in chair or bed >50% of the time). This is a good time to be thinking about terminal phase and put advanced care plans in place. Consider anticipatory medication, DNAR. Has the patient been seen or visited by a GP within 28 days?

Red: terminal phase. The patient is actively dying.

Indicators a patient maybe entering the terminal phase include extreme tiredness or weakness, becoming drowsier and being less responsive or less able to communicate. They may decline rapidly over days or hours, becoming bedbound for most of the day and need help for all personal care. There may be changes to their breathing (more shallow and noisier secretions), their ability to eat or drink, or be unable to swallow oral medication. The person may tell you or family members they think they’re dying.

When to involve the palliative care team

Much of the palliative care journey can be managed in general practice and automatic referrals should be avoided. The palliative care team can be a useful resource where there is complexity, severe or difficult to manage symptoms, complexity affecting choice of pain relief or symptom control medications (e.g. liver or kidney disease) or where there is a difficult balance between symptom control and side effects, such as drowsiness.

Palliative care and hospice referral may be indicated for support of the patient or family (e.g. counselling and social support), rehabilitation or physiotherapy if functional decline post treatment, or for hospice admission if not managing at home or approaching end of life and hospice is their preferred place of care or death.

Useful resources

Professional resources

RCGP Palliative and End of Life Care Toolkit

Marie Curie: Palliative Care Knowledge Zone

NICE – palliative care general issues

Scottish Palliative Care Guidelines

Marie Curie: Advanced care planning

Patient resources

Scottish Partnership for Palliative Care

Dr Nicolas Alexander is a GP and GP trainer in North East London, with an interest in palliative care. He gave this presentation at Pulse Live London earlier this year. If you want to see what is upcoming at Pulse Live, see our events hub here

Pulse 365 LIVE Events cover a broad array of topics pertinent to you, your patients, and your practice. You will gain free CPD and be able to take part in live Q&As. Specifically created for all practising, GMC-registered GPs and trainees, you will hear from experts across primary and secondary care, and network with like-minded GPs. Sign up for your nearest event today.

Pulse October survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens

Visit Pulse Reference for details on 140 symptoms, including easily searchable symptoms and categories, offering you a free platform to check symptoms and receive potential diagnoses during consultations.

Related Articles

READERS' COMMENTS [1]

Please note, only GPs are permitted to add comments to articles

There is still a tendency to associate strongly ‘palliative care’ with approaching death, forgetting sometimes the needs of patients for symptom palliation even in curable, self-limiting, or more chronic conditions.

All pain relief from painkillers is in a way ‘palliative’, even if it is to relieve pain from a traumatically broken bone; friendly contact can reduce distress from trauma or anxiety; and as yet, we have no treatment for ADHD which is not purely palliative.

sometimes we need to remember that all patients need palliation of pain, anxiety, distress; something which the current NHS is finding it increasingly impossible to provide to other than rich private patients – to the detriment of all as we become unskilled in it’s practice.