Update on the mpox outbreak – what GPs need to know

GP Dr Toni Hazell provides an update on the global mpox outbreak and explains current advice on identifying and managing suspected cases in the community

Introduction and epidemiology

Mpox is an infectious disease caused by the monkeypox virus (MPXV). The first human case was in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and there have been sporadic outbreaks outside of Africa since the early 2000s. It is divided into two genetic groups or clades – Clade I and II – all UK cases so far have been Clade II. Clade I has been seen in more African countries in 2024 than previously and has been detected outside Africa, but not yet in the UK.

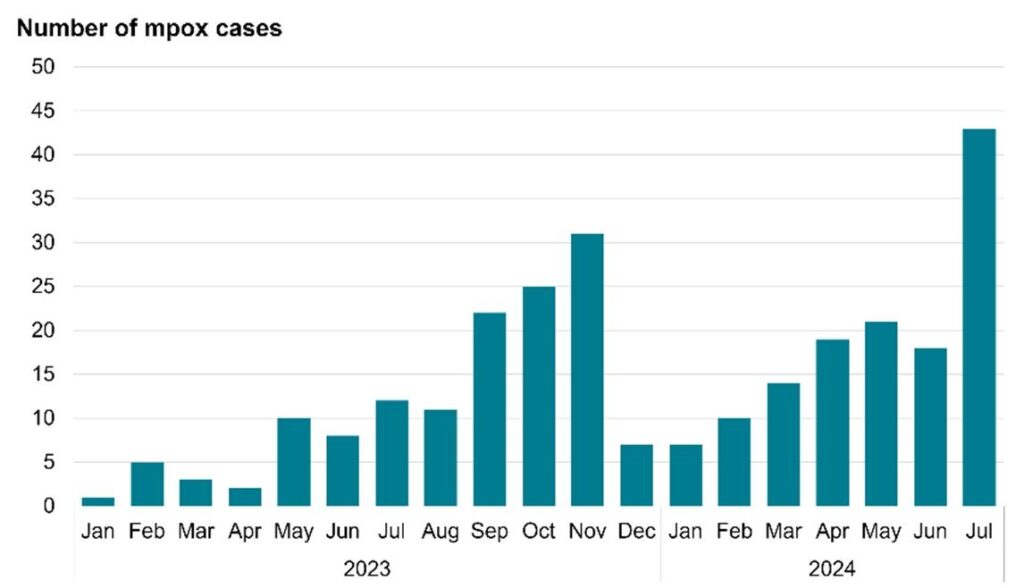

Between 2018 and 2021 there were seven UK cases, all with a clear link to travel, but mpox hit the headlines in 2022 when 3,732 UK confirmed or highly probably cases were reported, many in people with no clear travel links to endemic mpox areas. Numbers then reduced, with less than 10 cases per month in early 2023 but an increase was seen towards the end of 2023 and in mid-2024 (see Figure below).

Figure. Number of confirmed and highly probable mpox cases in England, by month in 2023 and 2024. Source: UKHSA. Mpox (monkeypox) outbreak: epidemiological overview. (Last updated 8 August 2024)

Mpox can be transmitted sexually. Airborne transmission is also possible, and mpox can also be transmitted by close non-sexual contact (eg, hugging), by direct contact with lesions or scabs, or with clothing, bedding or towels used by an infected person. Vertical transmission can lead to stillbirth and neonatal death.

The global 2022 outbreak mainly (but not exclusively) affected gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM) and was mostly sexually transmitted.

A wider demographic is affected in 2024, including heterosexual people and children.

Clinical features

An initial prodrome of fever, headache, myalgia, fatigue, chills and joint pain is followed by a rash within five days of the start of the fever. It begins on the face and then spreads elsewhere, including the palms, soles, mouth, anus and genitals. The rash evolves before scabbing; when all the scabs have fallen off, leaving unbroken skin, the patient is no longer infectious. This UKHSA guidance includes several example images of mpox lesions. Other symptoms can include those of proctitis, dysuria and odynophagia.

Mpox is usually self-limiting. Serious illness is more common in children, pregnant women and those with immunosuppression. Death is uncommon, with around 220 deaths from over 100,000 worldwide cases between January 2022 and August 2024. There have been no deaths in the UK so far and the case fatality rate is lower in Europe, at 4 per 10,000. Clade I remains classified as a high consequence infectious disease (HCID) in the UK, whereas Clade II has lost its HCID status. HCID mpox is more likely to cause severe symptoms.

Case definition

A patient has possible mpox if they fit one or more of the following criteria:

- Febrile prodrome (fever ≥38°C) with known contact with a confirmed case of mpox in the 21 days before symptom onset.

- Unexplained lesions, including (but not limited to) genital, oral or anal ulcers or nodules, or proctitis (eg, anorectal pain or bleeding), where the clinician has a suspicion of mpox.

The case becomes probable if there are unexplained rashes or lesions as above, in someone who fits one of the following criteria:

- They have an epidemiological link to a confirmed, probable or highly probable case of mpox in the 21 days before symptom onset.

- They identify as a GBMSM.

- They have had one or more new sexual partners in the 21 days before symptom onset.

Clade I mpox should be suspected in the following situations:

- Epidemiological link to a confirmed case of Clade I mpox, or a suspected case in countries where there may be a risk of Clade I exposure.*

- Travel history to countries with a risk of Clade I exposure.

*Note that at the time of writing, countries reporting lab-confirmed mpox Clade I include:

- DRC

- Republic of the Congo

- Central African Republic

- Burundi

- Rwanda

- Uganda

- Kenya

- Cameroon

- Gabon

Countries where there may be a risk of Clade I exposure (due to bordering DRC) are:

- Angola

- South Sudan

- Tanzania

- Zambia

Initial management in primary care

Mpox cannot be confirmed clinically, with chickenpox being a key differential. A GP who suspects mpox should discuss with their local infectious diseases (ID) team.

The UK Health Security Agency does not specify who should do initial testing, but as mpox is diagnosed using viral swabs, not usually available in primary care, logic suggests that it will be done in secondary care. Advice on PPE varies depending on the source, but any healthcare professional who will be within one metre of a patient with suspected mpox should consider wearing eye protection, gloves and a facemask. If Clade I mpox is suspected, PPE appropriate for a HCID must be used – this involves items such as an FFP3 respirator and hood which are unavailable in primary care.

In practice, the key message for primary care is to be aware of the countries where Clade I is present and to take a good history of travel or epidemiological links to these countries, to pass on to the ID team; they will discuss suspected cases with the imported fever service if Clade I mpox is suspected.

If you triage patients, by phone or electronically, clinicians should have a safe way of managing patients with suspected mpox who need to be seen. This might involve them entering the surgery by a back or side door and going directly into a side room, rather than sitting in the waiting room. If the patient can be classified as a suspected case using a combination of a phone call and photos, it may be appropriate to arrange for ID review without seeing the patient face to face, to reduce the risk of transmission to vulnerable patients at the surgery. For patients who walk in, your reception team should be empowered to ask those who raise concern to wait in a side room.

Clinical rooms should be cleaned after a patient with suspected mpox is seen, following standard decontamination guidance, examples of which are given here for England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. The gist is generally that disinfectant or detergent should be used, gloves worn, and if the patient is still in the room, a facemask and apron should also be worn, but local documents should be consulted if there is uncertainty.

Secondary care management

Management of mpox in secondary care is largely supportive, but there are antiviral drugs such as cidofovir and tecovirimat available for those with severe disease.

Contact tracing

For likely exposures within primary care there is advice available. (Note the advice concerns non-HCID cases, but pending further updates is also currently cited for HCID contact tracing). No action is needed for those who were in the same room but more than one metre away, or for healthcare professionals who saw a patient while wearing appropriate PPE. For those who examined a patient without PPE then all that is needed is monitoring and measures to avoid passing on undiagnosed mpox i.e. avoiding sexual contact for 21 days and ideally not travelling internationally. Child contacts do not need to stay off school. Only those at highest risk, who have had direct exposure of broken skin or mucous membranes to a patient with mpox (or their body fluids or potentially infectious clothes/bedding) need to consider possibly avoiding work for 21 days (after a risk assessment), or avoiding contact with pregnant women, children and immunosuppressed people.

Vaccination

Vaccination (a two-dose course) is currently offered at sexual health services (SHS) for GBMSM who are at highest risk (eg, those who have multiple partners, participate in group sex, have had a bacterial sexually transmitted infection in the last year, or attend sex-on-premises venues). It is also offered to close contacts of someone with mpox, ideally within four days of contact and definitely within 14 days.

Occupational vaccine may also be available for the following groups:

- Staff at sex-on-premises venues.

- Healthcare workers caring for those with confirmed or suspected mpox.

- Staff in laboratories where pox viruses are handled, or who work in HCID units.

- Staff who regularly decontaminate areas where there have been cases of mpox.

- Staff in SHS who assess suspected cases.

Dr Toni Hazell is a portfolio GP in London

Pulse July survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens

Visit Pulse Reference for details on 140 symptoms, including easily searchable symptoms and categories, offering you a free platform to check symptoms and receive potential diagnoses during consultations.