The patient’s unmet needs (PUNs)

A 28-year-old man who is new to your list, and whose records have not yet arrived, presents in your emergency surgery with a two-day history of substernal chest pain. He describes this as sharp and scratchy and says it is worse when taking a deep breath or lying down. He is normally in good health, apart from a recent mild flu-type illness, is not on any medication and has no family history of heart disease.

Examination reveals a well man, who is in mild discomfort, has no chest wall tenderness and whose observations are normal. You are surprised when the precautionary ECG done at the surgery shows ST elevation in most leads. You explain that you think he has an inflammation of the lining of the heart. ‘Not pericarditis again,’ he groans. ‘That’s the second time – I had it two years ago. Does it mean I’ve got to go to hospital again?’

The doctor’s educational needs (DENs)

What are the most common causes of pericarditis?

Pericarditis is inflammation of the pericardium. It is more common in men aged between 20 and 50 years.

Pericarditis is most commonly caused by a viral illness, for example the coxsackievirus, echovirus, adenovirus, mumps, varicella zoster virus and Epstein-Barr virus. Other causes include infections and inflammation in surrounding organs (pneumonia, oesophageal disease), post-myocardial infarction (Dressler’s syndrome), renal failure, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, malignancy and connective tissue disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, polyarteritis nodosum, systemic sclerosis and ankylosing spondylitis. But in 90% of the cases in the Western world the cause is idiopathic.

How does it usually present and how can the GP make a confident diagnosis?

Patients tend to present with chest pains after having had flu-like symptoms. Pericarditic pain is typically sharp and penetrating in quality and worse on inspiration, movement and lying flat. It is alleviated by sitting forward. It can sometimes radiate to the left shoulder or down the arm.

To diagnose pericarditis, a thorough history of symptoms prior to the onset of chest pains is key – cough, temperature, flu-like symptoms, diarrhoea, vomiting or symptoms causing suspicion of underlying malignancy.

Past medical history would include previous chemotherapy, any autoimmune conditions, renal failure, recent myocardial infarction, and any previous episodes of pericarditis. Patients who have had pericarditis will be prone to have it again. It is also important to bear in mind that pericarditis may be a late presentation of a large silent MI because of irritation of underlying myocardium and the pericardium.

On examination, a pericardial friction rub might be heard. To optimise the auscultation, position the patient supine, lying on their left side with their head resting on their left arm, or sitting forward. The friction rub tends to be best heard at the end of expiration. Red flags would include a combination of muffled heart sounds, raised jugular venous pressure and peripheral oedema. Alarming features would be hypotension and tachycardia. This would indicate tamponade due to pericardial fluid accumulation and is a clinical emergency.

To what extent are investigations necessary to establish an underlying cause? What investigations should be considered?

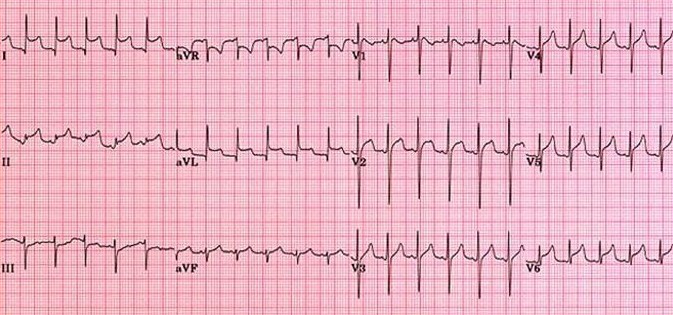

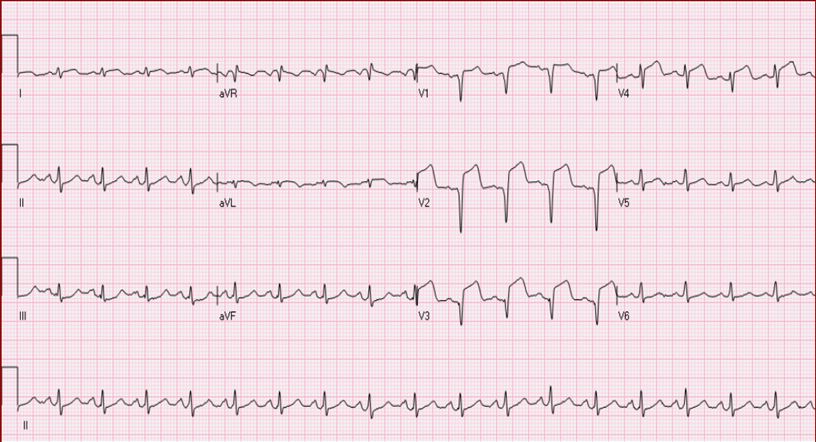

Useful investigations include an ECG, which is abnormal in 80% of patients with acute pericarditis. It tends to show a saddle-shaped ST segment elevation throughout all leads in the first stages (Figure 1). In contrast, myocardial infarction has ST elevation in some leads and ST depression in reciprocal leads (Figure 2). In later stages of pericarditis, generalised inverted T-waves may develop.

Figure 1 – typical pericarditis ECG

Figure 2 – STEMI

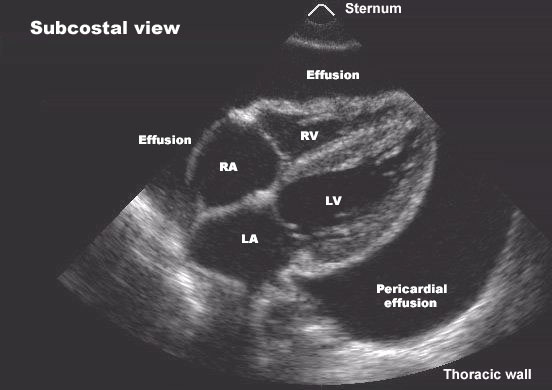

Bloods may show that inflammatory markers (CRP and ESR) are raised, along with troponins and creatine kinase. An echocardiogram is not diagnostic, but it helps to identify pericardial thickening, assess the LV function, and the presence of a pericardial effusion.

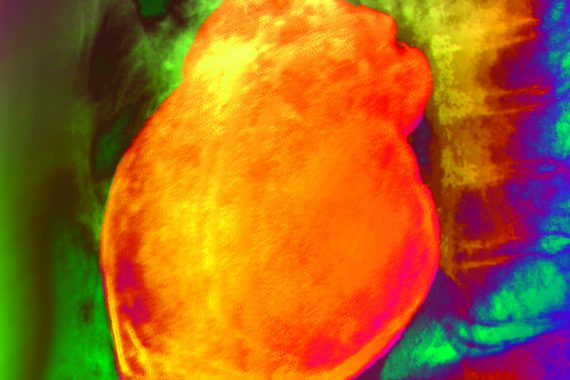

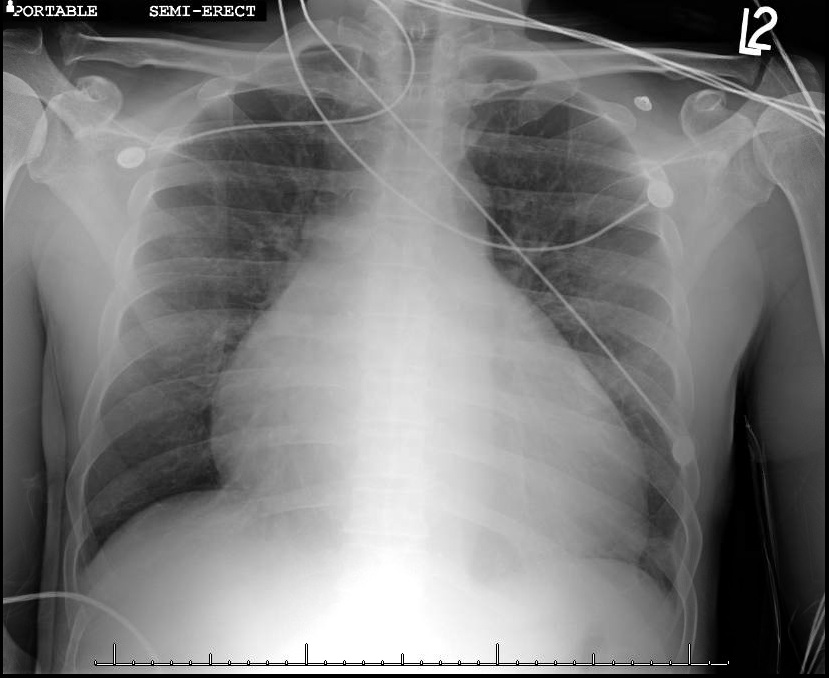

The latter in most cases of pericarditis does not develop. However, if an effusion is noted, it is significant if it is more than 1.5cm in width. This could lead to right ventricular collapse in diastole due to the pericardial fluid accumulation – for instance cardiac tamponade. On a chest X-ray the classic ‘water bottle’ sign, otherwise described as a globular heart, might be seen if there is significant pericardial effusion (see picture, below). An X-ray is useful to help identify any other causes of pericarditis such as an underlying malignancy.

Figure 3 – pericardial effusion leading to tamponade

Figure 4 – globular heart on CXR

The management of pericarditis is simple – anti-inflammatory medications such as ibuprofen, aspirin, indomethacin or alternatively colchicine (especially for patients with recurrent pericarditis). The symptoms tend to be alleviated fairly rapidly.

Do all cases require admission? If not, who should be admitted, and how should the GP manage those kept in the community? What complications might arise?

Patients who can be managed in the community include those who have had pericarditis before, are young, with few cardiovascular risks and who describe a typical pericarditic pain. ST elevations on ECGs should always be of concern and thus there shouldn’t be any hesitation in ringing for urgent cardiology advice or sending the patient directly to an ambulatory assessment area or to A&E for further examination.

Complications of pericarditis as mentioned above include a pericardial effusion, which can be monitored by echocardiogram and assessed by history-taking. A progressing effusion would give symptoms such as breathlessness, nocturnal orthopnoea, engorged neck veins and peripheral oedema.

Another complication is recurrence of pericarditis. Patients tend to get a second episode a few months later. Rarely, some patients can develop chronic constrictive pericarditis as a result of scarring and stiffening of the pericardial sac.

Dr Melissa Bouchard is a cardiology specialist trainee and Dr Sanjay Arya is consultant interventional cardiologist, at the Royal Albert Edward Infirmary, Wigan, Greater Manchester

Pulse October survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens