Continuing our series, musculoskeletal specialists Andrew Emms, Dr Greig Nicol and David Wilson outline how to manage common orthopaedics presentations remotely

Despite the shift towards remote consulting, many musculoskeletal presentations in primary care will require face-to-face examination. However, there are some conditions where a thorough remote assessment can provide a diagnosis or valuable initial information to guide appropriate referral. Here we outline some common orthopaedic presentations and how they should be approached remotely.

Suspected lumbar radiculopathy

Consider the following aspects of the history:

- Pain radiating in a dermatomal pattern below the knee, and paraesthesia and numbness, most often below the knee, are linked to lumbar spinal nerve root compression.

- Pain arising from other structures such as a disc or facet joint is unlikely to refer below the knee.1

- Disc prolapse is more common in middle age, with symptoms aggravated by flexion and rotation of the trunk, and any position that mimics the straight leg raise (SLR) – such as driving or putting on socks.

- Risk factors include family history of lumbar radiculopathy, sedentary lifestyle and use of vibrating machinery and heavy manual work involving bending and twisting.2

- Differential diagnoses include hip and knee pathology, vascular insufficiency, peripheral neuropathy and spinal claudication.

Remote examination

Patients with low back pain and radiating leg pain can be assessed by video consultation. First, observe the patient’s gait. Look for ataxia, which may indicate cervical myelopathy or cerebellar pathology, and high stepping, which can indicate lumbar motor radiculopathy.

Observe the spine and lower limbs, looking for spinal deformity, swelling, wasting and colour changes.

Ask the patient to walk on tiptoes (assessing for S1 power), walk on heels (assessing for L4 and L5 power) and to perform a single leg dip (standing on one leg and bending the hip and knee, assessing for L2, L3 and L4 power).

Observe the range of motion of the lumbar spine – flexion, extension and lateral flexion to each side.

Sitting active knee extension is useful as a modified SLR test to assess for nerve root tension. (ipsilateral SLR has greatest sensitivity and crossed sign has greatest specificity).

Sitting with feet planted on the floor and shoulder width apart, then letting knees fall in to touch one another is a useful screen for hip capsular pathologies, such as osteoarthritis (OA).

Investigations to arrange remotely

Some 60-80% of patients recover within six weeks, so symptomatic management is sufficient for non-urgent presentations. It may be reasonable to request investigations during this period in patients with uncontrollable pain.

If pain and disability remain high at three months, consider lumbosacral MRI. 70% of this group will continue to have pain at one year.

We would not routinely recommend nerve conduction studies (as these are more helpful for ruling out peripheral nerve pathology than ruling in lumbar radiculopathy) or X-rays.

Blood tests are only useful if there is a suspicion of inflammatory arthritis, spinal infection with systemic symptoms (chronic discitis often shows normal inflammatory markers and WCC and requires blood cultures) or a non-musculoskeletal suspicion is raised.

Remote management

Patients presenting with symptoms of less than three months duration and without symptoms prompting emergency or urgent assessment can be managed with analgesia, advice to stay at work and to remain functional.

Useful patient information includes the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy resource on low back pain and the Yoga for Backs website.

The natural history of sciatica is very favourable so a routine follow up is not necessary, unless symptoms worsen or fail to settle after six weeks. Advise the patient of what signs/symptoms could suggest a serious condition and what action to take. An NSAID can be prescribed, if safe and tolerated, or a weak opiate as second line therapy, in line with NICE guidelines.

Follow-up

Consider referral to a specialist if intrusive or disabling symptoms persist at three months. There is little evidence that any further intervention, including physiotherapy, will benefit the patient while waiting for surgery.

Red flags: Low back pain or radicular leg symptoms

Refer the following for emergency assessment:

- Major motor radiculopathy (loss of single leg antigravity tiptoe, heel walk or single leg dip)

- Deteriorating minor motor radiculopathy

- Any change in bladder or bowel habits, particularly when associated with sensory changes around the genitals, perineum or anus – requires urgent assessment for cauda equina syndrome

Hip pain

History is key: age, onset, trauma, symmetry, systemic symptoms and wider pain symptoms, augmented by simple examination, allow us to identify our first management steps in primary care.

First confirm that non-musculoskeletal causes can be excluded, including red flags. If yes, confirm that the hip joint is the main cause. This requires a combination of history and examination. Common musculoskeletal causes vary by age but overlap on a sliding scale. In younger patients these include: femoroacetabular impingement (FAI), dysplasia and stress fractures. In older patients, the commonest causes include OA, referred spine pain and greater trochanter pain syndrome.3

Basic remote hip examination

Movements are simple and yield useful information in conjunction with the history,4 so it is reasonable to examine at first contact by guiding the patient on the phone or camera by using verbal prompts on the following observations:

- Walking Note use of stick, antalgic gait or Trendelenburg gait (weakness of hip abductors causing pelvic tilt or droop on the opposite side).

- Location and nature of pain Ask the patient to point to where they feel most of the pain and where it radiates. Make particular note of where the pain originates. Pain focused over the lateral aspect or greater trochanter may relate to greater trochanteric pain syndrome or be referred from the back. Hip pathology can give rise to groin or buttock pain radiating to the knee and beyond.

- Straight leg raise Ask the patient to lie flat and perform an SLR of the unaffected limb and then the affected limb. Reduced SLR may be due to hip OA but also suggests back pathology so we can ask about neuropathic symptoms.

- Hip flexion In a lying position ask the patient to bring their knee up into their chest as far as possible.5 Compare with the unaffected side and look for pain or restriction. This may be associated with OA, labral tear or FAI.

- External rotation Ask the patient, in a lying position or sitting on the edge of a seat, to make a ‘figure of four’ with their legs (see picture, below).5 Restriction due to groin pain or stiffness may suggest OA of the hip which can radiate pain to the knee, while pain may be identified in the lumbar spine or sacroiliac joints if these are a cause.

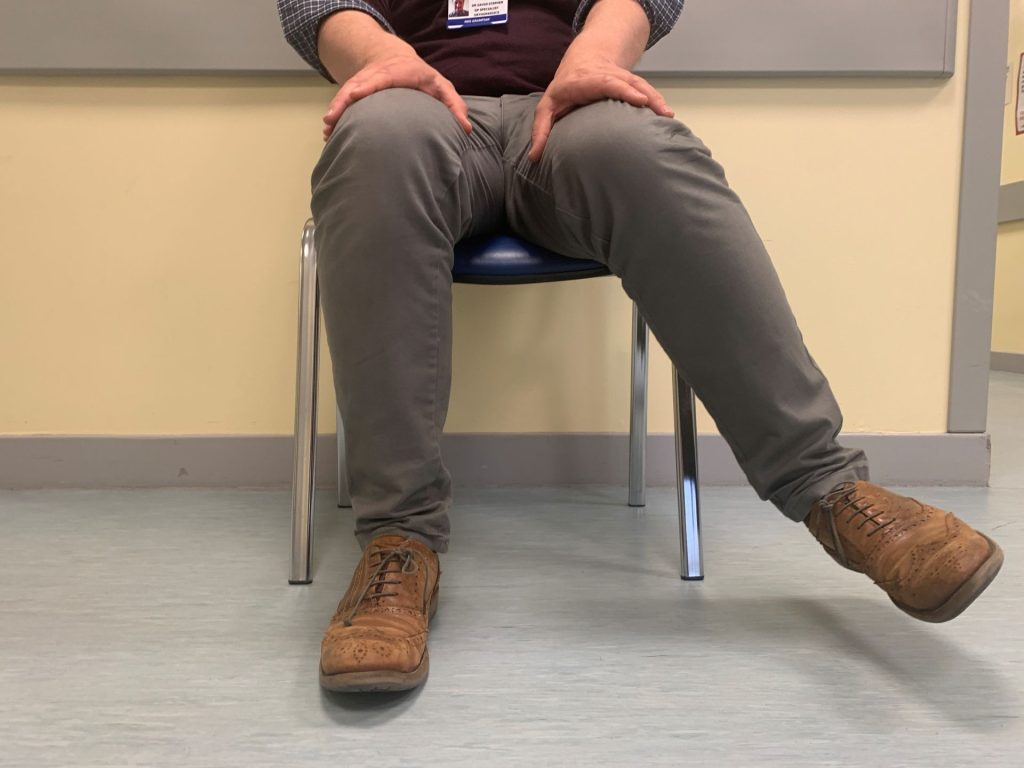

- Internal rotation In a sitting position with knee flexed at 90˚, ask the patient to place their hands on their lap to stabilise the thighs, then internally rotate the hip by lifting the foot away from the centre (see picture, below).5 This can identify pain or stiffness originating in the hip joint itself, possibly associated with FAI or OA.

If there is diagnostic uncertainty or the remote examination is unsatisfactory, arrange to see the patient face to face. Pelvic X-ray can help rule out differential diagnoses and is advisable before most routine referrals. Treatment options include onward referral to physiotherapy or orthopaedics.

Red flags: Hip pain

- Mass, deformity or swelling – suggestive of malignancy

- Red skin, fever or systemic upset – suggests infection; discuss with on-call orthopaedics team

- Acute severe hip pain, with: high energy impact trauma; low energy trauma in known osteoporosis; shortening of leg; external rotation of leg; sudden limitation of mobility or inability to weight-bear

Shoulder pain

Patients can be assessed and managed in some cases over the phone, or preferably by video.

Before starting the shoulder examination ask yourself: Are there red flags? Is the pain coming from the shoulder, neck or elsewhere?

Excluding the neck and instability

First screen the neck. Does the patient’s pain sound like radicular pain or radiculopathy? Ask the patient to move the neck. Ask them to look up to the ceiling, look to the floor, look to the right then left, then perform side flex ear-to-shoulder movement.

Ask if any of these movements reproduce the pain. If yes, follow spinal service guidelines. If uncertain, arrange a face-to-face consultation.

To check for instability, ask subjective questions, for example:

- Does the shoulder ever partially or completely come out of the joint?

- Does your shoulder ever dislocate during sport or certain activities?

If yes and the instability is atraumatic, refer to physiotherapy. If yes and the instability is traumatic, there are ongoing symptoms or it is atraumatic and no better with physiotherapy, refer the patient to the shoulder clinic or orthopaedics.

Remote examination

Once you have excluded red flags, cleared the neck and confirmed the shoulder is stable, you can proceed to the remote examination of the shoulder using the following three steps.

- Locate the pain Ask the patient to look in a mirror and compare any difference in where the collar bone meets the shoulder; ask them to palpate. Then ask them to elevate the arm out to the side to the top of the head to determine high pain arc. Also ask the patient to bring their arm across their chest.

- Pain provocation on these tests could indicate acromioclavicular joint disease. This requires physiotherapy referral; further intervention may include NSAIDs and steroid injection.

- Assess active and passive external rotation Ask the patient to keep their elbow at 90 degrees with it tucked into the waist. Ask them to keep the elbow tucked into their waist and rotate the arm to the side – a tip is to clamp a towel in the armpit so it cannot drop to the floor. Explain you need to assess this passively – can a friend or family member do this movement for them? Does the end feel hard? Can full range be achieved relative to the other side?

Loss of external rotation may indicate a glenohumeral joint pathology. Frozen shoulder is common among those aged 45-65 years or patients with arthritis over 60. Consider:

- X-ray to differentiate between frozen shoulder and glenohumeral joint OA.

- Physiotherapy referral.

- Self-management advice.6-11

- Medical management: NSAIDs, analgesia cortisone injection.

Assess pain on abduction and elevation Ask the patient to elevate the arm out to the side. Can they obtain full range? Is there a painful arc while doing this? The patient may describe pain half-way through the movement, which clears above their head. Ask them if pain is produced on liftingor pushing against the wall. In this case rotator cuff tendinopathy may be the likely diagnosis; it is common at age 35-75 years. Consider:

- Physiotherapy first line.

- Self-management advice.7-11

- Medical management if poor response to above: NSAIDs, analgesia, cortisone injection.

Red flags – shoulder pain

The following require emergency assessment:

- Trauma, pain and acute weakness.

- Any mass or swelling.

- Red skin, fever or if the patient is systemically unwell.

- Trauma, epileptic fit or electric shock leading to loss of rotation and abnormal shape.

Andrew Emms is a consultant physiotherapist at the Royal Orthopaedic Hospital in Bristol, Dr Greig Nicol is a GPwER in orthopaedics at NHS Grampian and David Wilson is a senior first contact physiotherapist in primary care in Bridlington and executive member of the Primary Care Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Medicine Society

References

- Bogduk N. Clinical anatomy of the lumbar spine and sacrum, 3rd edition. Churchill

Livingstone 1997 - Videman T et al. Lumbar spinal pathology in cadaveric material in relation to history of back pain, occupation and physical loading. Spine 1990;15:728-40

- Chamberlain R. Hip pain in adults: evaluation and differential diagnosis. Am Fam Physician 2021;103:81-9

- Cottrell M and Russell T. Telehealth for musculoskeletal physiotherapy. Musculoskeletal Sci Pract 2020;48:102193

- Nicol G and Stephen G. Telemedicine for orthopaedic assessment in primary care.

- Versus Arthritis. Shoulder pain.

- Versus Arthritis. OA of the elbow and shoulder.

- British Elbow and Shoulder Society. Subacromial shoulder pain.

- Chartered Society of Physiotherapy. Shoulder pain.

- NHS Torbay and South Devon. Torbay shoulder exercise programme.

- Derby Shoulder Unit. Derby shoulder instability rehabilitation programme videos.

Further patient resources – back pain

South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Patient information and educational resources. Facts on back pain, sciatica, how to manage long-lasting lower back pain and useful resources for self care.

Complete relevant Musculoskeletal medicine CPD modules on Pulse Learning by registering for free, or upgrade to a premium membership for full access at only £89 a year.

Pulse July survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens