1. Watch out for red flags

A history of significant acute trauma, symptoms suggestive of tumour or infection, or acute neurological or vascular dysfunction merit urgent investigation. Most other shoulder conditions can be safely managed with a combination of rest, analgesia, physiotherapy and steroid injections for a period of eight weeks before considering investigation.

2. Beware symptoms that are due to cervical spine disease rather than a shoulder problem

Pain that travels down the arm, past the elbow and into the forearm and hand, or that is constant even at rest during the day, or is made better by arm movement, may be due to a cervical spine problem. A good screening examination for the neck is Spurling’s test – if tilting the head towards the painful side and extending the neck at the same time reproduces arm symptoms, then the cause is probably cervical spine disease.

3. Use the age of the patient as a guide to diagnosis

Patients in their 20s and 30s are likely to have shoulder impingement without damage to the rotator cuff, or if there is a history of a sporting or other injury they may have a labral tear (the labrum is a ring of tissue deep in the shoulder joint that helps with stability). Middle-age patients are likely to have rotator cuff syndrome or frozen shoulder, while the elderly are likely to have a rotator cuff tear or arthritis.

4. Make sure you check for true stiffness of the shoulder

The best way to check for stiffness is to examine the passive range of external rotation of the shoulder with the arm at the side. This is because the active range of motion may be restricted because of pain, rather than true stiffness. Hold the patient’s elbow bent at 90 degrees with the arm tight against the side, ask the patient to go ‘loose’ and then gently rotate the forearm out to the side as far as possible, still holding the patient’s arm and elbow against their body.

If there is significant loss of passive external rotation, compared to the other shoulder, then the diagnosis is either arthritis of the shoulder joint or an established frozen shoulder. If there is no stiffness, the pain is probably due to rotator cuff syndrome (impingement/bursitis/cuff tear).

5. Remember to check both active and passive movements

Ask the patient to raise their arm. If they cannot raise it all the way up, gently support the arm and try and lift it further. If there is a lot more passive than active movement, and when you let go of the arm the patient is unable to keep it in an elevated position, then they probably have a large rotator cuff tear.

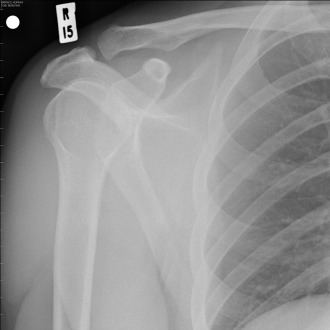

6. Consider ordering X-rays rather than an ultrasound

If the shoulder is stiff, X-rays will differentiate between a frozen shoulder (normal on X-ray) and arthritis (degenerative change on X-ray). X-rays should also be the first-line investigation in the elderly, as the rate of asymptomatic rotator cuff tear can be over 50% in this age group, so finding a tear on ultrasound doesn’t provide much more information.

7. Frozen shoulder has a slower history of onset

This can help you distinguish between frozen shoulder and calcific tendonitis. Both these conditions can cause severe pain and restriction of movement, but in frozen shoulder this develops more slowly over several weeks (pain first, followed by loss of movement), while an acute calcific tendonitis can happen very suddenly with the patient experiencing sudden spontaneous onset of both severe pain and loss of movement.

8. Remember that a rotator cuff tear does not always need a repair

Most rotator cuff tears occur because of a slow process of gradual tendon deterioration. A useful analogy to use for patients is to liken the tendon to a rope which is frayed because some of the strands have parted, but the rope is still working as it should. A trial of conservative treatment for four to six months is appropriate, with analgesia, physiotherapy and even one or two steroid injections. However, if there is a history of trauma in a previously asymptomatic shoulder with subsequent significant symptoms, then consider an early referral.1

9. Have confidence if performing a steroid injection

Although accurate placement of injections (subacromial for rotator cuff syndrome, glenohumeral for frozen shoulder or arthritis) is desirable, evidence suggests that they are effective even if not injected precisely where intended.2 Both the posterior and lateral approaches for injection are very safe with minimal risk. Although laboratory evidence suggests repeated high doses of steroid can be detrimental to tendon tissue, there is no evidence to suggest that one or two shoulder injections are harmful even in the presence of a chronic rotator cuff tear.

10. Don’t let a young patient become a recurrent dislocator

Young patients under the age of 25 who have dislocated their shoulder because of an injury are at high risk of subsequent recurrent dislocation. A high proportion of these patients can slip through the net if their shoulder is reduced in the emergency department and they are then discharged – they frequently do not attend a subsequent fracture clinic because their shoulder feels better, or they do not get referred. However, an increased amount of subsequent dislocations correlates with future risk of post-traumatic arthritis and it is worth referring these patients early for a specialist opinion.3

Mr Adam Rumian is a consultant orthopaedic surgeon and specialist in shoulder and elbow surgery at East and North Hertfordshire NHS Trust

References

Pulse October survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens