The acute red eye is an extremely common presenting complaint and differentiating between benign and sight-threatening conditions can sometimes be daunting. While the hospital ophthalmology department may be dominated by slitlamps and complex imaging equipment, most sight-threatening disease can be identified from the history and the simple tools available to all GPs.

Case 1

The patient, a two week old child, attended the surgery with his mother. The pregnancy and birth had been uneventful. A purulent discharge from both eyes had been present from six days postpartum. Tarsal and bulbar conjunctival inflammation was present in both eyes. Topical chloramphenicol drops were prescribed but no improvement in the condition was seen.

Two weeks later, the patient attended the hospital emergency eye clinic, where conjunctival swabs confirmed Chlamydia infection. The patient was prescribed a two-week course of systemic erythromycin and made an uneventful recovery. The patient’s mother was referred to the genital urinary medicine department for further investigation, treatment and contact tracing.

GP’s diagnosis

Bacterial conjunctivitis

Actual diagnosis

Neonatal Chlamydial conjunctivitis

Clues

Conjunctivitis in the neonatal period should always be treated with high suspicion. The infective organism is acquired at the time of birth from vaginal mucosa. Chlamydia is a common cause of neonatal conjunctivitis and may be complicated by Chlamydia-related pneumonia and systemic infection. Gonorrhoea is a less common cause of neonatal conjunctivitis but can be complicated by corneal ulceration, central nervous system involvement and systemic infection.

Take-home message

The pathogens associated with neonatal conjunctivitis may cause severe ocular disease and potentially life-threatening systemic illness. Appropriate microbiology investigation with bacteriology and chlamydial swabbing should be performed at first presentation. It is appropriate for topical antibiotics to be started at the GP practice, but ophthalmology involvement is required if chlamydial or gonococcal infection is identified.

Case 2

Mr Y, a 60-year-old, presented to his GP with a painful, pink left eye and epiphora of three day’s duration. A careful history revealed that he had also been off work recently with flu-like symptoms. The GP noted diffuse conjunctival inflammation and epiphora of the left eye, and a diagnosis of conjunctivitis was made and topical chloramphenicol prescribed.

One week later the patient returned with continuing symptoms. In addition, he described blurry vision of the left eye. Ocular examination was unchanged. As the patient had forgotten his usual spectacle prescription, visual acuity testing was performed with a ‘pinhole’ and was found to be 6/6 in each eye. With this in mind, the GP prescribed a lubricant eye drop with instructions to return in a week if there is no change.

Two days later, the patient attended the local eye emergency clinic, where a dendritic ulcer was seen. Topical antivirals were prescribed with subsequent resolution of the ulcer, but with persistent corneal scarring.

GP’s diagnosis:

Conjunctivitis

Actual diagnosis:

Herpes simplex keratitis

Clues

Herpes is more likely to reactivate when the patient is debilitated, for instance, due to systemic illness. Additionally, after one week, additional ocular symptoms should prompt thinking down a different diagnostic line.

Take home message

1. Measuring visual acuity with a pinhole is often used as a substitute for appropriate refractive correction, but a pinhole can also correct reduced visual acuity due to corneal opacity or cataract. Measurement of acuity with the patient’s own spectacles would have identified reduced visual acuity.

2. Corneal staining with fluorescein must be carried out to look for evidence of dendritic ulcers in a patient with persistent ocular inflammation.

3. Presence of a dendritic ulcer requires urgent ophthalmology referral to prevent permanent scarring.

Case 3

A 66-year-old lady presented to the general practice with a two-week history of a unilateral painful red eye, foreign body sensation, photophobia and blurry vision. Consecutive topical courses of fucithalmic ointment and chloramphenicol drops did not resolve her symptoms. Three weeks later, she presented to the local hospital’s emergency eye clinic. Her visual acuity had decreased to “hand movements acuity” in the affected eye.

Examination revealed conjunctival injection, corneal ulceration and corneal neovascularisation. The patient was admitted to hospital for intensive topical antibiotics, but progressive corneal thinning led to corneal perforation.

Due to severe corneal scarring the patient’s visual acuity did not improve.

GP’s diagnosis

Bacterial conjunctivitis

Actual diagnosis

Bacterial corneal ulcer with perforation.

Clues

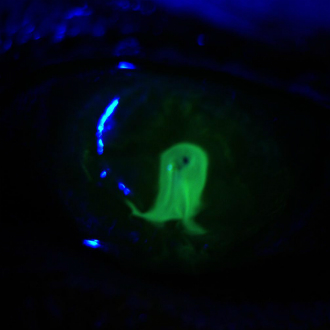

History of foreign body sensation, pain, photophobia and sight loss. Salient examination findings include peri-limbal conjunctival injection, a white opacity to the cornea, which stains with fluorescein (Fig. 1). In addition to staining corneal epithelial defects, topical fluorescein may be used to aid the diagnosis of corneal perforation, where diluted fluorescein appears to flow from the site of perforation (Seidel’s sign – Fig. 2)

Fig.1: Corneal ulcer with severe conjunctival injection. Note the central perforation ‘plugged’ with iris pigment.

Fig.2: Seidel’s sign. Leaking aqueous fluid dilates the instilled fluorescein and causes appearance of fluorescein flowing from the perforation.

Take home message

Differentiating conjunctivitis and corneal ulcers:

Conjunctivitis (viral, bacterial or allergic)

– Global redness of the conjunctiva.

– Follicules or papillae often present on the tarsal conjunctiva.

– Watery, purulent or mucopurulent discharge.

– Not associated with pain, photophobia or visual loss.

– Often self-limiting.

Corneal ulcers

– Contact lens wear is the greatest risk factor and a history of lens wear should raise suspicion of corneal ulceration.

– Redness of the conjunctiva is more often peri-limbal.

– Pain and foreign body sensation.

– Visual loss.

– Often associated with other ocular pathology (e.g. dry eye, blepharitis).

– The clarity of the cornea may be reduced (can iris details be clearly seen?)

Dr Alan John Connor is a consultant ophthalmologist, and Dr Chris Matthews is a registrar in ophthalmology, both at Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

Mr Henry Grantham is a medical student at Newcastle University.

Pulse October survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens