GP beware – paediatrics

Case 1

George is two months old and is brought to his GP by his mother with a cough and inspiratory stridor. This started during the night and he has been coryzal for 24 hours. His mother reports that he has always been a noisy breather. Systemically, he appears well, and apart from inspiratory intermittent stridor he has a small capillary haemangioma on his left shoulder.

His GP reassures the mother that this is viral croup and prescribes a dose of dexamethasone. George settles in the next few hours, but re-presents to the GP three weeks later with similar symptoms. Again, George has been coryzal. He appears relatively well and it is diagnosed as croup again.

On the third manifestation of stridor two weeks later, George’s mother takes him to A&E in the night because he is struggling to breathe. He is given oral dexamethasone and nebulised budesonide and settles somewhat. He is admitted by the night paediatric team and diagnosed as ‘recurrent croup’. Over the next few hours, George’s condition deteriorates, requiring intubation and ventilation and transfer to the regional paediatric intensive care unit, where he undergoes endoscopy of his airway.

GP and junior paediatric team diagnosis

Viral croup progressing to recurrent croup.

Actual diagnosis

Subglottic capillary haemangioma.

Clues

Croup-like symptoms in those less than one year old is a red flag. Viral croup usually peaks by the age of two years and usually does not recur. The fact that George is so young and his symptoms were recurring suggests a structural airway problem that needs prompt referral for a paediatric ENT assessment. The noisy breathing since birth may have been related to his underlying airway obstruction. A concurrent viral illness would have exacerbated his airway reserve. A history of difficulty in feeding and reflux-like symptoms can also be present. In this case, the capillary haemangioma on the skin was a big clue, as they can also manifest in the airway. Other causes of structural airway problems include:

• Something within the airway such as a foreign body.

• Problems with the airway wall or structure such as tracheo-laryngeo-bronchomalacia, subglottic stenosis (usually a history of prior intubation), laryngeal cleft or laryngeal web.

• Something compressing the airway – vascular ring, mediastinal or neck mass.

Take-home message

Croup-like symptoms in children under one year and recurrent croup in any age group requires careful assessment for an underlying airway abnormality.

Case 2

Chloe is an eight-year-old girl who attends A&E after accidentally tipping a hot cup of coffee onto her feet and legs. She has sustained superficial burns to about 1% of her body surface area. Apart from this mild superficial burn, she appears to be in good health and is sent home with appropriate dressings.

Some 48 hours later she is taken to see her GP because she has a fever, a pink blanching rash, diarrhoea and generalised muscle aches. Apart from looking a bit miserable, she seems not to show any sign of infection and the burn site looks healthy. The mother says that there were quite a few kids in A&E with diarrhoea and vomiting and thinks Chloe may have caught something from them. A presumed diagnosis of viral gastroenteritis is made and the child is sent home with advice to stay hydrated.

Over the following night, Chloe’s fever continues and the out-of-hours GP is called. Chloe appears sleepy, is febrile at 39°C, and tachycardic with a heart rate of 160bpm. She feels cool peripherally. Given the background of loose stool and suspected viral gastroenteritis, the tachycardia is put down to the fever and sleepiness to the time of night. By the next morning, Chloe is drowsy and floppy. She is taken to hospital by ambulance, where in A&E they are unable to record her blood pressure and she requires aggressive fluid resuscitation together with the commencement of intravenous antibiotics and mechanical ventilation on a paediatric intensive care unit.

GP diagnosis

Gastroenteritis.

Actual diagnosis

Toxic shock syndrome (TSS).

Clues

TSS most commonly occurs in the under-25 age group and results from a systemic inflammatory response to staphylococcal or streptococcal toxins, otherwise known as super-antigens. TSS usually follows burns or skin injuries, which may be trivial. Secondary infected chicken pox is another commonly associated illness. When super-antigens come into contact with patients’ cells they react with various consequences depending on cell type:

• Activation of blood vessel muscle cells leads to vasodilation and a fall in blood pressure.

• Activation of skin lymphocytes causes a non-purpuric, red rash that later peels.

• Activation of gut lymphocytes leads to diarrhoea.

• Activation of muscle cells leads to muscle pain and cramps.

Other clues were the altered level of consciousness, cool peripheries and a disproportionate tachycardia to the fever (the heart rate is expected to rise by 10bpm with each degree Celsius rise above 37°C); all of these suggest haemodynamic shock.

Take-home message

TSS may mimic a viral illness, but beware. The presentation of fever, diarrhoea, irritability and altered level of consciousness, a rash, tachycardia out of proportion to the fever, low blood pressure, skin peeling (late sign) following a burn, a superficial skin infection or secondary infected chicken pox should alert the clinician to the possibility of TSS and prompt urgent referral to hospital.

Case 3

Abdul is three years old and presents to his GP with a limp that has been going on for three days. He had a cold about 10 days ago, but otherwise he is fit and well. There is no history of fever. He is up to date with vaccinations and has had a BCG.

On examination, he appears systemically well and there are no signs of injury. He can walk but he is limping on his right leg. He is not in pain and has a full range of movement in his lower limb joints. A transient synovitis is suspected and his parents are reassured and advised to return in one week if symptoms persist.

A week later, Abdul is brought back and sees a different GP for general malaise and fatigue with a cough, but no fever. His limp has been intermittently better and worse over the past few days. He looks generally okay but is tired and miserable and his throat is a bit red. He is given a course of amoxicillin to cover for an upper respiratory infection.

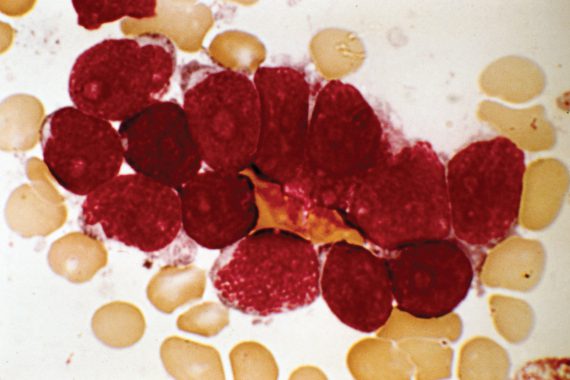

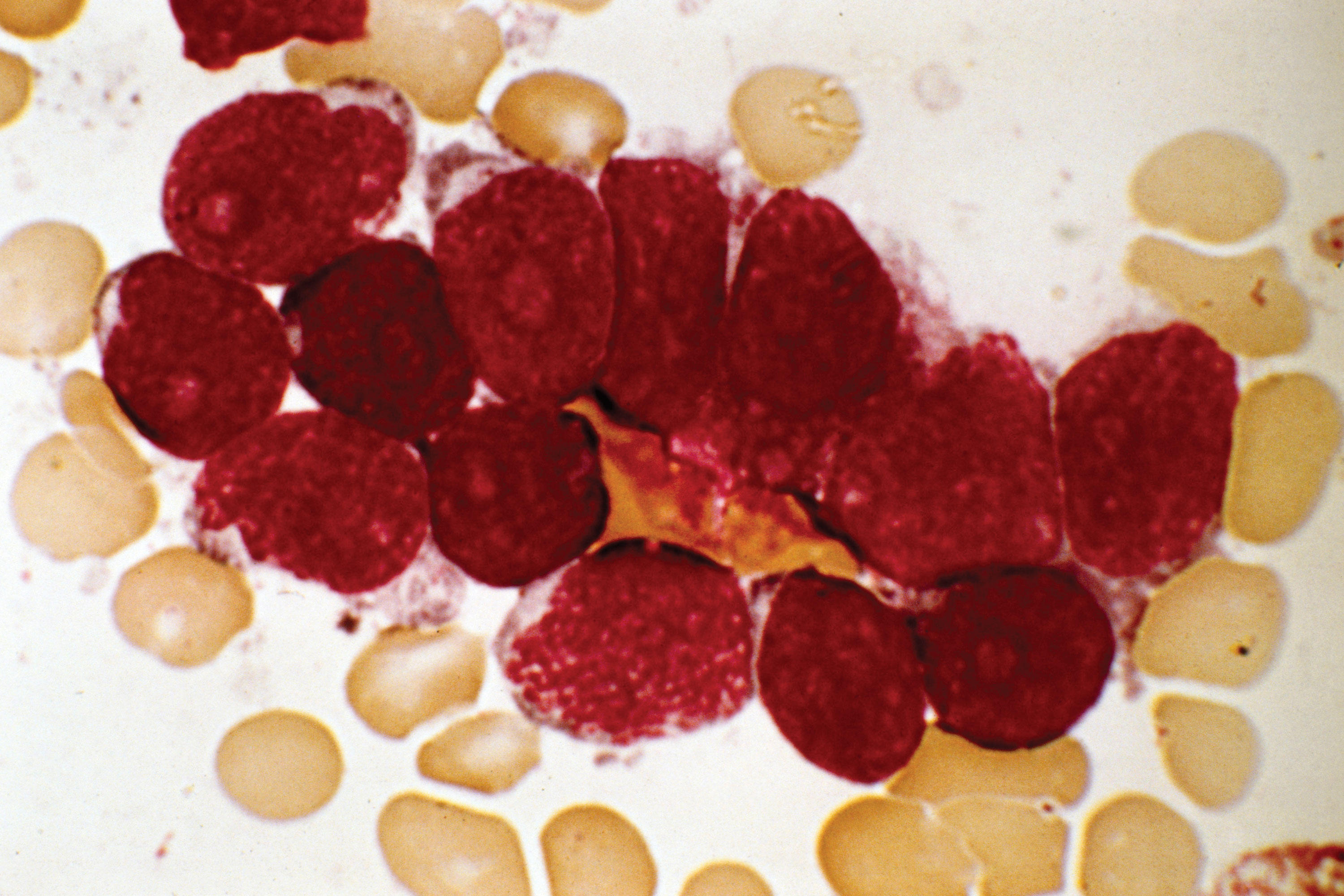

He presents to A&E on a bank holiday weekend, 10 days later, with a fever and cough. He looks pale and generally miserable. In the context of limping and fever, blood tests are done together with X-rays of the right hip and knee. X-rays are normal but his blood tests show an Hb of 6, platelets 80, and a white cell count of 2. A blood film shows blast cells.

GP diagnosis

Transient synovitis; upper respiratory tract infection.

Actual diagnosis

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia.

Clues

Initial assessment was reasonable after a short history of a limp with a preceding viral-like illness in a well-looking child without a fever. But a limp that persists, however mild, needs further assessment and urgent referral. In the context of fever, a septic arthritis would need to be ruled out. In this case, the history of fatigue and malaise is a clue to underlying illness, and Abdul was also found to be anaemic. The key things to investigate in a child with a limp are:

• Bony injury (history and physical signs should point to this).

• Septic arthritis (if history of fever or red swollen joint).

• Leukaemia (possible history of fatigue, recurrent infections and easy bruising owing to bone marrow failure).

• In addition to the above, consider Perthes avascular necrosis of the femoral head in children aged four to 10 years, and slipped upper femoral epiphysis in the older child.

Take-home message

A limp persisting for more than one week needs urgent referral, and immediate referral if there is history of fever, joint swelling or injury.

Dr Claire Lemer is a consultant in general paediatrics at the Evelina London Children’s Hospital, St Thomas’ Hospital.

Dr Peter Lillitos is a specialist registrar in paediatrics at the Evelina London Children’s Hospital, St Thomas’ Hospital.

Visit Pulse Reference for details on 140 symptoms, including easily searchable symptoms and categories, offering you a free platform to check symptoms and receive potential diagnoses during consultations.