How not to miss pneumothorax

Worst outcomes if missed

- Death – although mortality from pneumothorax is generally low, with rates of 1.3 and 0.6 per million per year for men and women respectively. Secondary pneumothorax has a higher rate of mortality than primary pneumothorax, with figures quoted as high as 15% of patients.

- Chronic respiratory impairment, including respiratory failure – may occur over time if a significant pneumothorax is left untreated and the patient already has underlying lung impairment due to another disease process.

Epidemiology

There are two types of pneumothorax to be aware of – primary and secondary. Primary spontaneous pneumothorax (PSP) occurs without any known underlying disease and stereotypically affects tall, thin, young men. These patients, if they undergo surgery, are often found to have small areas of weakness (apical ‘blebs’) or peripheral lung changes akin to emphysema. Secondary disease occurs in the presence of a known pulmonary disease such as COPD. Patients who smoke, even those without emphysema, are much more likely to develop a pneumothorax – excess risk is up to 22 times for men and eight times for women.

There is very little contemporary data, or any data specific to the UK, regarding the true incidence of pneumothorax or how many of them present to primary care. For all types of pneumothorax, figures from the early 1990s would suggest that an average-sized UK practice of 6,500 patients might expect to see just under one male patient per year and one female patient every three years or so, although repeat consultations may make these figures a slight overestimate. Modern referral pathways mean the overwhelming majority of these patients are likely to end up being seen and definitively treated in secondary care. However, there are increasing calls to either manage patients with pneumothorax conservatively with close observation, or as ambulatory outpatients using Heimlich (one-way) valves.1,2

It is also important to note that recurrence is common in the absence of definitive surgical intervention – around 40% have a second episode, which can affect either the contralateral or ipsilateral side, usually within the following two years.

Symptoms

- Sudden or rapid-onset dyspnoea, although occasionally this is completely absent in PSP. Also ask about reduced exercise tolerance in the less mobile.

- Chest pain (often pleuritic).

- Deterioration in an underlying respiratory condition, possibly leading to increased cough, wheeze or need to use an inhaler more frequently.

Signs on respiratory examination

- Reduced chest movement on affected side.

- Hyper-resonant percussion note.

- Reduced vocal fremitus.

- Reduced breath sounds (although a reasonable amount of air needs to be present for this to be found).

- Hypoxia may be present, although this can be compensated for by increased respiratory rate and may not be seen in the younger or fitter patient.

- Pneumothorax may also manifest as an apparent exacerbation of an underlying condition, for example, wheeze.

- More rarely, there may be a subcutaneous emphysema or mediastinal ‘click’ on auscultation.

If there is evidence of laboured breathing, tracheal deviation (away from the pneumothorax), respiratory distress or cardiac compromise (low blood pressure or tachycardia) then a life-threatening tension pneumothorax must be ruled out. Patients may be hypoxic but this is not an indication of tension in itself.

Differential diagnoses

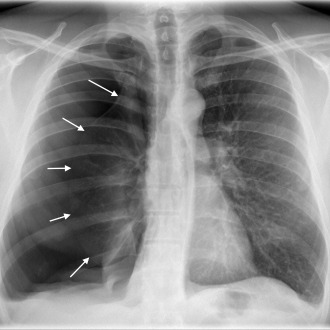

The differential diagnosis of dyspnoea is wide, and without the benefit of immediate radiology there can be great difficulty in identifying a pneumothorax in patients who also have a background of underlying lung disease such as COPD, asthma or fibrosis, as symptoms may well mimic those of a standard exacerbation (see picture)

A good factor to focus on initially would be duration of onset. Gradual, progressive breathlessness makes pneumothorax less likely; sudden symptoms, especially if associated with pain, make it more so. GPs need a low threshold for chest X-ray in those who describe a pattern or severity of exacerbation different from what they have had before, or in those who are deteriorating or not improving despite treatment.

Five key questions

- Has the patient’s exacerbation gone on too long, been more severe than usual or not responded to treatment?

- Is there a family or personal history of pneumothorax, or of connective tissue disease?

- Is the patient a smoker (tobacco or cannabis)?

- Is there a recent history of chest trauma or iatrogenic instrumentation?

- Is there any underlying lung disease such as COPD or asthma?

Pleuritic pain may be due to:

- Infection – look for fever, bronchial breathing or localised crepitations on auscultation, or discoloured sputum.

- Pulmonary embolism – assess for DVT and other risk factors; chest examination should be relatively normal.

- Angina – this is likely to be obviously induced by exercise and relieved with glyceryl trinitrate.

- Musculoskeletal pain – assess for pinpoint tenderness and a suggestive history.

Decreased air entry and reduced chest movements may be caused by pleural fluid, pleural thickening or dense consolidation, but the timeframe for these developing will usually be less acute and a dull percussion note would be the norm.

Hyper-resonance may be caused by COPD or acute asthma, but this will typically be bilateral.

Investigations

The most efficient way to diagnose a pneumothorax is a chest X-ray, although some are only seen clearly with CT scan.

Suspected tension pneumothorax is

a life-threatening emergency needing immediate needle decompression and requires either on-site treatment or

a blue-light admission to A&E. Suspected non-life threatening pneumothorax should be referred to either A&E or the acute medical ward.

Dr Rahul Bhatnagar is a pleural clinical research fellow and Dr Nick Maskell is a reader in respiratory medicine, both at the University of Bristol’s academic respiratory unit. Dr Maskell is also a consultant chest physician at Southmead Hospital in Bristol.

References

- Brims FJ, Maskell NA. Ambulatory treatment in the management of pneumothorax: a systematic review of the literature. Thorax 2013;68:664-9

- Simpson, G. Spontaneous pneumothorax: time for some fresh air. Internal Medicine Journal, 2010;40:231-4

Further reading

Visit Pulse Reference for details on 140 symptoms, including easily searchable symptoms and categories, offering you a free platform to check symptoms and receive potential diagnoses during consultations.