Respiratory clinic – pulmonary tuberculosis

A 35-year-old male presents to his GP with a cough and fevers. After taking a history, other features of night sweats, yellow sputum production and weight loss are ascertained. His symptoms have been increasing over the past month and he is now struggling to work.

On examination, a few crackles are audible at the right apex and cervical lymphadenopathy is present.

The problem

Tuberculosis (TB) is still a significant problem in both developing and developed countries, the World Health Organisation estimates 8.6 million people developed the disease worldwide in 2012.1 Recently released figures show the UK’s incidence of TB remains one of the highest in Europe, 7,892 new cases of TB were reported in the UK in 2013.2

TB cure rates following treatment are very good. However, to control the spread of TB, early detection and prompt treatment of active infectious cases is required. TB is often insidious in onset, and so a high index of suspicion is needed to make a diagnosis.

Features

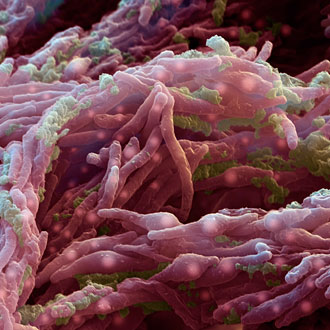

TB is an air-borne bacteria and an individual suffering from pulmonary TB can transmit the infection to 10 to 15 people over the course of a year.3 Around 5% of those infected have early progression to active TB, whereas the other 95% have latent TB, where the disease is ‘contained’. Those with latent TB can progress to reactivation if they become immunocompromised with a lifetime risk of TB estimated at 15%. Pulmonary TB is the most common site of disease, but TB can occur in the nodes, central nervous system, GI tract or bones. The following deals with the pulmonary aspect of the disease.

Pulmonary TB symptoms:

– Cough with or without the production of sputum.

– Chest pain.

– Dyspnoea.

– Haemoptysis.

– Weight loss.

– Fevers.

– Night sweats.

However, the sensitivity of these common symptoms in isolation is very poor, making a diagnosis of TB more challenging. In primary care, it is important to consider TB if any of the above symptoms are present and if they have risk factors for TB (as outlined below). Requesting a chest X-ray early in combination with these allows for an increase in diagnostic sensitivity.4

The likelihood of developing active TB is greater if the patient is:

– Born in an endemic country (such as Indian subcontinent/Africa) or a recent arrival.

– A recent contact of an infectious case of TB.

– Homeless.

– Alcohol dependent or drug abuser.

– HIV positive or immunocompromised.

– Suffering from malnutrition, chronic kidney disease or has diabetes.

It is important to also consider TB when symptoms do not improve even in a non–high risk patient and a Chest X-ray in that setting is an appropriate investigation as a useful discriminator.

Diagnosis

If TB is suspected, perform a chest X-ray, and if suggestive of TB proceed to further diagnostic tests. An urgent referral to the local TB service should be made.

Other tests that may be performed when the patient is seen in secondary care include:

– A Mantoux/tuberculin skin test, being read 48 to 72 hours after administration. False positives may occur with previous BCG vaccination or non-tuberculosis mycobacteria infection. False negatives also occur with very young age, recent TB infection (within eight to 10 weeks of exposure) or very old TB infection.

– Interferon gamma release assays (IGRA). There are two currently available – the T-spot and quantiferon. These quantify the interferon gamma released from lymphocytes sensitised to M.tuberculosis. The IGRA results are not affected by previous immunisation but cannot differentiate between latent and active disease. Given a false negative result in approximately 15% of active disease cases, they are not sufficiently sensitive to rule out active disease.

– Bronchoscopy/induced sputum

Management

– TB is treated with rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol for a two-month intensive phase to kill active multiplying bacteria. Rifampicin and isoniazid are then continued for a further four-month continuation phase to destroy slow growing bacteria.

– TB therapy may be extended if a patient has any drug resistance or has central nervous system disease.

Monitoring needed for treatment/side-effects:

– Rifampicin causes orange secretions. It is a potent inducer of liver enzymes, thereby reducing the effect of warfarin, sulphonylureas and the oral contraceptive pill. Alternative contraception should be used.

– Isoniazid – peripheral neuropathy may occur in malnourished patients and pyridoxine is given to prevent this.

– Ethambutol can cause retrobulbar neuritis. Initially, this will present with colour vision loss, which is reversible if ethambutol is stopped.

– Rifampicin, isoniazid and pyrazinamide can all cause hepatitis.

– Baseline LFTs and visual acuity are performed prior to starting treatment.

Public health must be notified of any active case and contact tracing undertaken as part of the secondary care TB service.

TB affects other sites, and the diagnosis of this can be difficult and requires a high index of suspicion.

Professor Onn Min Kon is a consultant respiratory physician and lead clinician for the tuberculosis service at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust.

Dr Sarah Appleton is an FY2 at North West London Hospitals NHS Trust.

References

[1] World Health Organisation. Global tuberculosis report 2013. Geneva: WHO; 2013

2 Public Health England. Tuberculosis notifications by site of disease (respiratory/non-respiratory), England and Wales, 1913-2012. London: PHE; 2013

3 Public Health England. 1913-1982 Statutory Notifications of Infectious Diseases (NOIDs); 2010-2012 Enhanced Tuberculosis Surveillance (ETS), Centre for Infectious Disease Surveillance and Control. London: PHE

4 van’t Hoog AH, Langendam MW, Mitchell E et al. A systematic review of the sensitivity and specificity of symptom- and chest-radiography screening for active pulmonary tuberculosis in HIV-negative persons and persons with unknown HIV status. World Health Organisation Report, 2013

Visit Pulse Reference for details on 140 symptoms, including easily searchable symptoms and categories, offering you a free platform to check symptoms and receive potential diagnoses during consultations.