Case 1

Mr F, a 69-year-old retired engineer, presented to his GP with a three-week history of worsening breathlessness, an intermittent cough and some wheezing at night. His symptoms had come on while on holiday recently, but had become worse on returning to the UK. He had a history of hypertension that was usually well controlled, but had not attended for regular blood pressure checks in the last 12 months. He was an ex-smoker and had no other past medical history of note.

A brief examination revealed a soft systolic murmur and occasional rhonchi, but was otherwise unremarkable. The GP diagnosed COPD, pending spirometry, and initiated bronchodilator therapy in the form of a salbutamol inhaler.

A week later, Mr F returned with worsening symptoms of breathlessness. His GP added a course of oral steroids and arranged to see Mr F back the following week. Two days later, Mr F was admitted to his local hospital with acute pulmonary oedema requiring intravenous diuretics and a prolonged hospital stay.

GP’s diagnosis

Chronic obstructive airways disease secondary to smoking.

Actual diagnosis

Congestive heart failure secondary to ischaemic heart disease.

Clues

Persistent unexplained breathlessness, particularly in a patient with risk factors and a systolic murmur.

Take-home message

Cough and wheeze may be presenting symptoms of heart failure. Peripheral oedema is often a late finding. The diagnosis of heart failure should always be considered in patients with recent onset of breathlessness, particularly if there are risk factors for, or a history of, ischaemic heart disease. Clinical findings in support of the diagnosis are an elevated venous pressure, a displaced apex and the presence of a mitral regurgitation/systolic murmur.

Case 2

Mrs L, a 48-year-old primary school teacher, arranged to see her GP with a one-week history of lethargy, fever and muscle aches. Four weeks previously, she had visited her dentist with a dental abscess, but otherwise reported no other past medical history of note apart from mild seasonal asthma. On checking her records, a history of minor mitral valve prolapse was noted on an echocardiogram five years previously, but this was not followed up further. Her GP diagnosed influenza and advised bed rest and paracetamol.

The following week she returned to the surgery, although on this occasion she did not see her regular GP. Her fever and lethargy symptoms had continued, but she had also begun to experience some breathlessness and a cough. Examination of her throat as well as otoscopy was unremarkable. Auscultation of the chest revealed some wheeze and a few crepitations. The GP diagnosed a chest infection and prescribed a course of amoxicillin with arrangements for a further appointment the following week if her symptoms did not resolve.

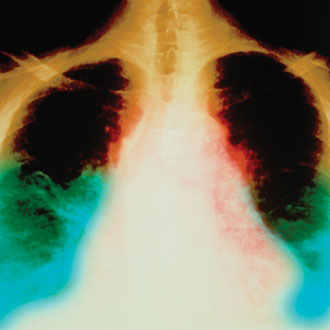

That weekend, Mrs L went to her local A&E as her breathlessness had become dramatically worse. A chest X-ray demonstrated pulmonary oedema and further subsequent investigation revealed mitral valve endocarditis with severe regurgitation. She went on to mitral valve replacement and made a good recovery.

GP’s diagnosis

Chest infection, recent viral illness.

Actual diagnosis

Infective endocarditis of the mitral valve with severe regurgitation.

Clues

Unexplained pyrexia in a patient with even minor valve disease, along with a recent dental infection.

Take-home message

Infective endocarditis, although rare, is a serious life-threatening condition with mortality rates of over 25% in some studies. The presence of an ongoing fever should prompt formal cardiac auscultation to identify new murmurs. Elevated inflammatory markers and night sweats should also further raise the index of suspicion. Once suspected, prompt referral should be made for echocardiography and discussion with a local cardiologist is advised.

Case 3

Mr M, a 56-year-old data clerk, saw his GP at the insistence of his wife after he had noticed discomfort in his neck while watching his local football team at the weekend. His symptoms had come on gradually over six weeks, but were becoming more severe.

On further enquiry, he had also noticed similar symptoms on one occasion during an argument at work. He denied any exertional symptoms but admitted to having a very sedentary lifestyle. He had recently given up smoking and was also known to have a slightly elevated cholesterol, which was being managed through dietary modification, but was otherwise well on no regular medication. He was not a regular attender at the surgery and had missed an appointment earlier in the year for a repeat cholesterol and blood pressure check.

Physical examination was entirely unremarkable apart from an elevated BMI. Mr M’s GP diagnosed muscular neck pain related to poor posture at work. He prescribed analgesia in the form of ibuprofen and made arrangements for physiotherapy at the local hospital.

A week later, Mr M presented with acute inferior MI to his local hospital and was treated with primary angioplasty and stenting of his right coronary artery.

GP’s diagnosis

Muscular neck pain.

Actual diagnosis

Recent-onset angina.

Clues

Pain in neck or throat brought on by emotional stress in a patient with risk factors.

Take-home message

Angina most commonly presents with chest pain, but can cause localised discomfort anywhere from the jaw line to the navel. Symptoms can be brought on by both physical and emotional stress (‘test-match angina’), and should prompt further evaluation, particularly if risk factors for ischaemic heart disease are present.

Dr Jerome Ment is a consultant cardiologist at the Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust

Pulse July survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens