Complicated pregnancy clinic: Diabetes

Dr Tara Lee discusses pre-pregnancy management, control regimes, gestational diabetes and postnatal care of women with pre-gestational diabetes

Diabetes is the commonest medical complication of pregnancy affecting 5-10% of pregnancies.(1,2) Gestational diabetes (GDM), accounts for >80% of these pregnancies. The remaining 20% of pregnancies involve pre-gestational diabetes: type 1 diabetes (T1D), type 2 diabetes (T2D), various forms of monogenic and other rarer types of diabetes. Some women may also be diagnosed with pre-gestational diabetes during pregnancy as part of screening for GDM.

Gestational diabetes

Most women with GDM go on to have a healthy baby and normal pregnancy but if untreated, it can cause complications for both mother and baby. Babies are more likely to be large for gestational age (LFGA). Mothers may need assistance to deliver the baby, such as induction or caesarean section, to reduce the risk of shoulder dystocia. The baby is more likely to develop neonatal jaundice, hypoglycaemia or need NICU care and there is a very small increased risk of stillbirth or neonatal death. LFGA babies and their mothers also have a higher risk of becoming overweight or obese and developing T2D in later life. This can be mitigated by a healthy lifestyle.

Diagnosis of GDM

All women will be checked for GDM risk factors (see box 1) at their antenatal booking appointment. Those with risk factors will be offered a 75g 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test between 24 and 28 weeks’ gestation.

Women who have had GDM in a previous pregnancy will also be offered testing in the form of self-monitoring of blood glucose from early in pregnancy or an OGTT in early pregnancy. If results are normal, this will be repeated at 24 to 28 weeks. Testing is also offered to women with significant glycosuria in routine antenatal care (one occasion of 2+ or more on urine dipstick or 2 or more occasions of 1+ or more urine dipstick).

Women diagnosed with GDM will be referred and reviewed within a week by specialist diabetes in pregnancy antenatal teams.

Box 1: Risk factors for developing gestational diabetes

- BMI > 30kg/m2

- Previous macrosomic baby weighing 4.5kg or more

- Previous GDM

- Family history of diabetes (first-degree relative)

- An ethnicity with high prevalence of diabetes

(South Asian, Black, Chinese or Middle Eastern origin)

Management of GDM

Management is coordinated by diabetes in pregnancy antenatal teams. Women are taught to self-monitor their blood glucose by capillary finger sticks, with advice to test at least 4 times a day: fasting and one hour after meals.

Initial management involves dietary and exercise advice including switching from high to low glycaemic index foods and exercising regularly (e.g. walking for 30 minutes after a meal). Women may also need metformin or insulin. They are reviewed in clinic at least every 4 weeks to support their glucose self-management. They are offered 4 weekly ultrasound scans from 28 to 36 weeks to assess fetal growth. Women with uncomplicated GDM are advised to give birth no later than 40 weeks plus 6 days.

After delivery, blood glucose-lowering therapy should be stopped immediately. Women will be monitored to exclude persisting hyperglycaemia in hospital before discharge.

Postnatal care and considerations for future pregnancies and health

Women who develop GDM have a 50% risk of developing T2D in the next 5-10 years after the pregnancy. Women whose blood glucose levels returned to normal after delivery, should have a fasting plasma glucose or HbA1c test from 6 weeks postnatal. For practical reasons, this is often performed at the 6-week postnatal check.

Women with a fasting plasma glucose <6.9mmol/l or HbA1c <48mmol/mol, should continue to follow GDM lifestyle advice and should be referred to the NHS Diabetes Prevention Programme. They should have their HbA1c checked annually. These women also have a 1 in 3 risk of developing GDM in subsequent pregnancies and should notify their GP or community midwife when booking to facilitate screening from the antenatal team early in pregnancy.

Pre-gestational diabetes

In England, more than 175,000 women of reproductive years live with T1D and around 200,000 with type 2 diabetes (T2D), accounting for 40% of all females with T2D.(3) Rates of GDM are increasing in line with rising obesity, so further increases in T2D are likely. Early onset T2D is more severe compared with later onset T2D and is associated with higher risk of micro- and macrovascular complications and reduced life expectancy.

Complications of pre-gestational diabetes

Pre-gestational diabetes is associated with increased risk of complications for both the mother and fetus.

Pregnant women with T1D are more likely to experience severe hypoglycaemia and diabetic ketoacidosis. Pregnant women with T1D or T2D may experience worsening of diabetes microvascular complications (retinopathy and neuropathy) alongside increased chance of obstetric complications such as pre-eclampsia and serious adverse pregnancy outcomes (congenital anomaly, stillbirth and neonatal death). One in two pregnancies in women with diabetes are complicated by preterm birth, large for gestational age babies, neonatal respiratory distress, hyperbilirubinaemia, hypoglycaemia and/or admission to the neonatal care unit. Recent national data showed that stillbirths and neonatal deaths now occur more in pregnancies with T2D than T1D.(4)

Optimising maternal glycaemia before and during pregnancy can reduce these risks. However, achieving and maintaining target glucose levels throughout pregnancy is challenging, because of gestational changes in insulin resistance and increased day-to-day variability in insulin pharmacokinetics. Furthermore, the tighter pregnancy-specific targets increase the risk of severe hypoglycaemia with potentially serious consequences for the mother. Women may find the situation distressing because of the enormous burden of self-care. Women often describe managing diabetes in pregnancy as an additional full-time job.

Pre-pregnancy care for pre-gestational diabetes

NICE recommends that every contact with women with diabetes from adolescence onwards should involve an explanation of the benefit of preconception blood glucose management and record the patient’s plans for pregnancy and conception.

Women should be reassured that, if they are able to plan their pregnancy, the risk of serious complications (such as stillbirth, serious cardiac or birth defect) drops to the usual background risk. As pre-pregnancy care is so important, women with diabetes who are planning a pregnancy or not on reliable effective contraception should be encouraged to take up referral to specialist pre-pregnancy diabetes clinics.

NICE recommends aiming for an HbA1c <48mmol/mol prior to conceiving, with monthly monitoring for women planning a pregnancy. However, any improvement in HbA1c and glycaemia will reduce the risk of complications. Women with a HbA1c >86mmol/mol should use safe effective contraception until they are able to lower their HbA1c.

Women with T1D are also at higher risk of severe hypoglycaemia and ketosis in the first few weeks of pregnancy so they should be prescribed glucagon and ketone strips and meters. They should be reminded to test for ketones when hyperglycaemic or unwell and to ensure hypo treatments are easily available. Partners and family should be offered training to administer glucagon if needed.

All women with pre-gestational diabetes who are planning pregnancy or not using reliable effective contraception should be encouraged to take high dose (5mg) folic acid daily. Apart from insulin and metformin, safety data on other glucose-lowering medications are scant. NICE recommends women should be switched from these prior to pregnancy.

ACE-inhibitors and AIIRAs can be continued for renal protection and then stopped as soon as pregnancy is confirmed. If they are used for blood pressure control, women should be switched to alternative pregnancy-appropriate antihypertensives at that point. Statins should also be stopped prior to pregnancy or as soon as pregnancy is confirmed.

Women should be assessed for microvascular complications while planning for pregnancy, to allow for optimisation, stabilisation or treatment of any nephropathy or retinopathy.

Management of pre-gestational diabetes

All pregnant women with pre-gestational diabetes should be referred to specialist diabetes in pregnancy antenatal teams for management as soon as they find out they are pregnant (by the next working day). They are usually reviewed before the formal booking appointment with the community midwives. To reduce the risk of pre-eclampsia, all women with pre-gestational diabetes should start low-dose aspirin from 12 weeks’ gestation.

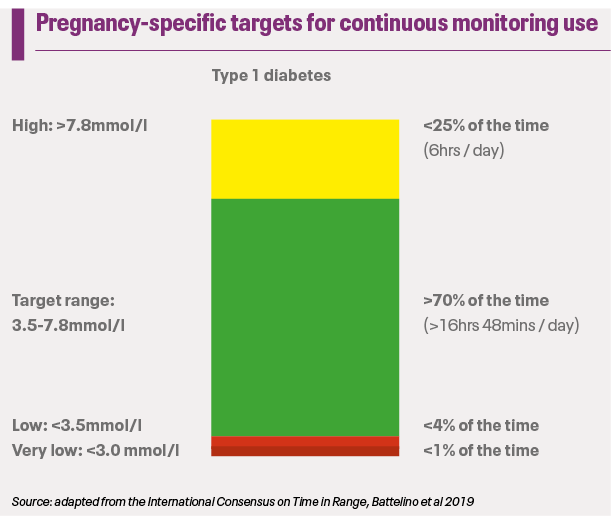

All women with T1D should be offered real-time continuous glucose monitors (CGM) to help meet pregnancy-specific glucose targets. These are small devices which sit on the skin and have a small subcutaneous cannula which measures interstitial glucose levels. Results are sent every 5-8 minutes to a receiving device (smart phone or receiver) in real-time, with alerts to notify the user if their levels are going high or low. This adds an extra level of safety as symptoms of hyper- and hypoglycaemia can change in pregnancy.

Box 2: NICE targets for capillary blood glucose for GDM

Fasting: <5.3mmol/l

1 hour postprandial: <7.8mmol/l

If managed with insulin: aim to maintain levels >4mmol/l

Standard of care for monitoring T2D is capillary blood glucose testing (fasting and postprandial). Though CGM can be used by patients with T2D and GDM, there is insufficient evidence to guide blood glucose targets and this will be guided by specialist diabetes in pregnancy teams.

Women with pre-gestational diabetes are reviewed in the antenatal clinic every one to two weeks to help support and guide their diabetes self-management. They will also have 4 weekly ultrasound scans scheduled from 28 to 36 weeks for fetal growth. Regular retinal screening will also be coordinated for booking (prior to 10 weeks) and each trimester. Delivery is recommended by 38 weeks and 6 days.

Considerations for pre-gestational diabetes during pregnancy

Insulin requirements change drastically over the course of pregnancy. For the first 8 weeks, women with T1D often experience very labile and exaggerated hyper- and hypoglycaemia. For some, this is one of the first signs of pregnancy.

From 8 weeks’ gestation, insulin sensitivity increases, leading to a propensity to hypoglycaemia. This is often exacerbated by nausea and vomiting of pregnancy and the uncertainty of oral intake to guide bolus insulin dosing. It is important to have a low threshold for offering antiemetics to women with diabetes in pregnancy.

From around 16 weeks’ gestation, insulin resistance increases continuously until close to the end of the third trimester. Insulin requirements can double or triple over the course of pregnancy and repeat prescriptions often need to be adjusted to accommodate this.

Diabetes devices (such as CGM and insulin pumps) are increasingly used in pre-gestational diabetes. Glitches and failures can occur, so it is important for anyone using technologies to have glucose meter strips and insulin pens on their prescription as a back-up for safety.

Postnatal care

As soon as the placenta is delivered, insulin requirements drop rapidly, often to below pre-pregnancy levels.

Clinicians will make a postnatal insulin plan with women with T1D, which will either revert to pre-pregnancy doses or halve the end of pregnancy doses. Women should be mindful of hypoglycaemia especially when feeding. They may need to snack prior to feeding their baby and are encouraged to ensure hypo treatments are readily available.

For women who were not using insulin pre-pregnancy, insulin is usually stopped after delivery. Their treatment depends on their pre-pregnancy glucose-lowering medications. Whilst in hospital following delivery their blood glucose levels will be monitored to check for uncontrolled hyperglycaemia. Metformin can be safely continued during breastfeeding but NICE advises avoiding other glucose-lowering medications.

Box 3: Postnatal care following discharge from antenatal services

- Fasting glucose / HbA1c from 6 weeks PN

- If fasting plasma glucose <6.9mmol/l OR HbA1c <48mmol/mol

- Continue GDM lifestyle advice

- Referral to NHS Diabetes Prevention Programme

- Annual HbA1c check to screen for diabetes

- Notify GP / community midwife early for subsequent pregnancies

Postnatally, women should be referred back to their usual diabetes care providers. Women often feel abandoned and alone postnatally, because of the reduction in intensity of follow up compared to pregnancy.(5) The first 6-12 months postnatally is challenging, with conflicting demands of the newborn and continuing self-management of their changing blood glucose levels. Blood glucose levels are harder to manage with infant feeding, inconsistent routine and resolving pregnancy hormones. This is often an opportunity to engage and transition women with pre-gestational diabetes to the linked hospital diabetes department, maintain improvements in their diabetes self-management achieved during pregnancy and help support them through the immediate postnatal period.

Diabetes in pregnancy is both medically and emotionally challenging for the woman. However, with increasing awareness and resources, we can better support these women to have healthier and more enjoyable pregnancies.

Resources:

- Diabetes UK: Planning for a pregnancy when you have diabetes

https://www.diabetes.org.uk/guide-to-diabetes/life-with-diabetes/pregnancy

- Tommy’s Planning for Pregnancy Tool

https://www.tommys.org/pregnancy-information/planning-pregnancy/planning-for-pregnancy-tool

- Diabetes UK: Managing your diabetes during pregnancy

https://www.diabetes.org.uk/guide-to-diabetes/life-with-diabetes/pregnancy/during-pregnancy

- Diabetes UK: Your guide to gestational diabetes

https://www.diabetes.org.uk/diabetes-the-basics/gestational-diabetes

- RCOG: Gestational Diabetes Patient information leaflet

https://www.rcog.org.uk/for-the-public/browse-all-patient-information-leaflets/gestational-diabetes/

References

1. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Diabetes in pregnancy: management from preconception to the postnatal period. NICE guideline [Internet]. 2020; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng3

2. Feig DS, Hwee J, Shah BR, Booth GL, Bierman AS, Lipscombe LL. Trends in incidence of diabetes in pregnancy and serious perinatal outcomes: a large, population-based study in Ontario, Canada, 1996-2010. Diabetes Care. 2014 Jun;37(6):1590–6.

3. Celik A, Forde R, Racaru S, Forbes A, Sturt J. The Impact of Type 2 Diabetes on Women’s Health and Well-being During Their Reproductive Years: A Mixed-methods Systematic Review. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2022;18(2):e011821190403.

4. Murphy HR, Howgate C, O’Keefe J, Myers J, Morgan M, Coleman MA, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women with type 1 or type 2 diabetes: a 5-year national population-based cohort study. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. 2021 Mar;9(3):153–64.

5. Dahlberg H, Berg M. The lived experiences of healthcare during pregnancy, birth, and three months after in women with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2020 Dec;15(1):1698496.

Visit Pulse Reference for details on 140 symptoms, including easily searchable symptoms and categories, offering you a free platform to check symptoms and receive potential diagnoses during consultations.