How to spot zebras – Huntington’s disease

‘When you hear hoofbeats, think of horses not zebras.’ The old adage is well known to GPs but what should you do on the rare occasion that you’re faced with a zebra and not a horse? Test your knowledge of identifying rare diseases with our new series on spotting unusual conditions in the surgery.

What is it?

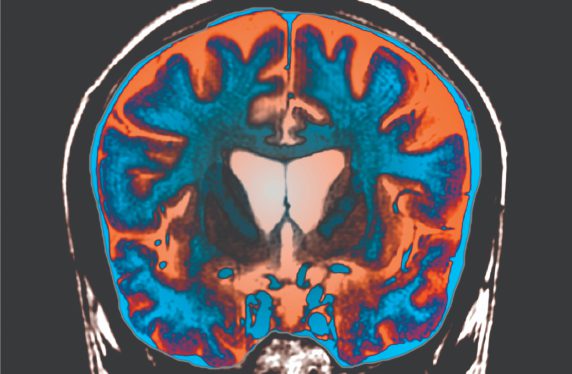

Huntington’s disease is an inherited autosomal dominant condition for which the gene was identified in 1993. The mutant gene leads to an expansion of a triplet repeat (CAG), which results in a mutant form of the protein huntingtin. This protein, which is expressed in every cell of the body, over time leads to cellular dysfunction and death, especially in specific areas of the brain, notably the cortex and the striatum leading to the characteristic motor, cognitive and psychiatric features of the condition.

A key thing to remember about Huntington’s disease is it has a T in it, not a D! I get more referrals for Huntingdon’s chorea than I do for Huntington’s disease, which takes its name from George Huntington who described the condition in 1872, in his one and only paper.

Prevalence

Most GPs will never see a case of Huntington’s disease, but given its genetic nature, some will see many affected family members. The condition typically presents in midlife but can present at any age. Those developing the condition before the age of 21 are defined as having the juvenile form of the disease, although this is rare, comprising fewer than 5% of cases. However, patients can present late in life, and the oldest patient I have seen with new-onset Huntington’s disease was 89 years old.

In the UK the number of people with the condition is estimated to be around 6.7 per 100,000 of the population, although this may be an underestimate as the majority of people at risk of carrying the gene do not come forward for testing.

Presentation

The typical presentation of Huntington’s disease is a combination of involuntary symmetrical dance-like movements (chorea), a change in personality and cognitive decline. However, patients can present with different combinations of these features, and exactly why this happens is not known. In the very earliest stages of the condition it can be hard to be certain that patients have Huntington’s disease, especially as insight is often impaired and so patients are often unaware that there are any problems. Indeed this can even be the case in patients with overt disease. Conversely, some patients who have undergone positive predictive testing for the Huntington’s disease gene can see every abnormality as a feature of the disease starting. As such, we prefer to use the term premanifest and manifest, as opposed to presymptomatic and symptomatic to describe these situations.

Diagnosis

Some clues that I have found helpful in diagnosing the onset of Huntington’s disease are:

- The presence of involuntary movements in bed at night, typically noticed by the partner.

- The development of relationship problems, difficulties at work and coping with complex situations.

- Subtle changes in cognitive performance and mood control – for instance, getting more worked up than usual over issues that would have been regarded as trivial.

While none of these are diagnostic, the combination raises the possibility that the condition has started. In juvenile cases, the patient typically presents with no chorea, but slowness of movement, dystonia, a failure to keep up at school and behavioural issues.

Over time, the features become more obvious and the diagnosis becomes straightforward – especially if the patient has already had a predictive gene test or comes from a family with Huntington’s disease. Occasionally though, patients can present without a family history and this can be for a number of reasons:

- The patient is not related to the parents biologically.

- The parents died early in life before they had time to present with Huntington’s disease.

- Parents died of conditions that were erroneously diagnosed as something else – such as dementia, parkinsonism.

- The development of a new pathological expansion of the CAG repeat (>39 CAG repeats), typically from a parent with an intermediate allele length (>27 and <36 repeats).

Differential diagnosis

There is often a limited differential diagnosis in Huntington’s disease, given its genetic nature. However, in juvenile cases the disease can present in the absence of any family history and so it can take a while to recognise that there is an organic neurological problem rather than a behavioural issue. In young women, chorea and cognitive changes can occur in systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid syndrome, and these diagnoses need to be considered, especially when there is no family history of Huntington’s and other systemic medical problems are present.

In older patients, there are rare causes of chorea including polycythaemia rubra vera and thyrotoxicosis, although I have never seen a case of either of these. Finally there are other rare genetic causes of Huntington-like syndromes, but these are typically diagnosed in specialist centres in patients with the Huntington’s disease phenotype and a negative genetic test for Huntington’s disease.

Investigation

The investigation of someone presenting with Huntington’s disease is relatively easy, although not necessarily straightforward given the genetic basis of the condition and its implications for all family members. Therefore, in a case where Huntington’s disease is suspected because of clinical signs and symptoms, referral to a neurologist is recommended so that a diagnostic genetic test can be done after appropriate counselling. In patients who have no features but want to know whether they carry the gene, a predictive test can be arranged. This is best done by referring the individual (and family members if requested) to clinical genetics for counselling and testing.

Any patient with known Huntington’s disease is best referred to a specialist clinic, of which there are many now. These clinics are multidisciplinary and link to regional advisers of the Huntington Disease Association (HDA) who are a valuable source of help for families and health professionals.

Follow-up

Most patients with Huntington’s disease are followed up in these specialist clinics. Some patients are not because of their neurological disability. Others have no desire to be seen as they feel fine. Managing such patients can be difficult as they can live chaotic lives, which impacts on local services and on some occasions leads to criminal activities. Rarely, patients can come to medical notice through this route, and Huntington’s disease is worth considering in such cases.

In addition, the genetic nature of Huntington’s disease can also create problems when family members are not open about having been diagnosed or having the test. This can create tension with the family and also generate ethical questions, when it becomes known that an affected parent, for example, had the condition but concealed it from their children who may have gone on to have children of their own and are blind to this information.

As for treatment, this is the preserve of specialist clinics but it is worth knowing about these as patients do not always make it to the clinic. The drugs that nowadays are commonly used to treat Huntington’s disease are olanzapine for the chorea, sleep problems, weight loss and mood swings that commonly dominate the clinical picture, tetrabenazine for the chorea, citalopram or mirtazapine for the depression and for the mood swings lamotrigine or sodium valproate.

Professor Roger Barker is a professor of clinical neuroscience at the University of Cambridge and an honorary consultant in neurology at Addenbrooke’s Hospital

Visit Pulse Reference for details on 140 symptoms, including easily searchable symptoms and categories, offering you a free platform to check symptoms and receive potential diagnoses during consultations.