Cover story main image, August issue 2017 3×2

Any GP practice trying to recruit a partner recently may have noticed that they are rarer than hen’s teeth. And many predict it is going to get worse.

A top official at NHS England said in 2014 that GPs’ independent contractor status would be ‘gone in 10 years’.

Even the RCGP chair Professor Helen Stokes-Lampard recently told a committee of peers: ‘While personally I love the partnership-led model of general practice, I know it is not likely to be fit for the long-term future.’

Amid such gloomy predictions, the voices of the future of general practice are rarely heard.

But now, a major nationwide Pulse survey of GP trainees – the first ever conducted by this magazine – suggests they greatly value the partnership model of general practice, but want to reshape it for a new age.

Only 10% of the 310 respondents ruled out ever taking on a partnership, and as many as 40% said they expect to have a partnership role within five years of training , in line with other recent surveys.1

However, this doesn’t tell the full story. Of those trainees who want to become partners in the long term, only half cite this as their only likely role. This may reflect greater uncertainty over long-term plans, but a significant number of these aspirant partners see their day job as one element of a wider portfolio career, which they will blend with working in academia, the military, CCGs, occupational health, or even tech start-up companies.

Trainees want more time to explore other interests

Dr Donna Tooth

And, generally, those who want to go into partnership do not want to do so immediately. Instead, they want to start their career as sessionals, with around 70% of all respondents wanting to be salaried, locum, or a mix of both, one year after training.

Dr Samira Anane, chair of the GPC trainees committee, says: ‘Partnership is not dead and a significant proportion of trainees continue to be interested in becoming partners, but not necessarily straight after CCT.

‘In general practice we have a long history of portfolio careers for GPs of all backgrounds, irrespective of their contractual status. The changing landscape means that these opportunities are increasing all the time.’

Dr Anane’s predecessor on the committee, Dr Donna Tooth, says she would like a partnership, but envisages combining this with working on a disability tribunal.

Dr Tooth says: ‘I think newly qualified GPs will be more attracted to partnership if it’s as part of a portfolio career. I think a partnership may not in itself be sufficient for the new generation, who will want a reduced number of sessions with more time exploring other interests.’

The attraction to partnership is partly the chance to control their own careers.

As GPST1 in Bristol Dr Jason Sarfo-Annin puts it, the next generation are less willing to give up their autonomy – and that makes general practice attractive.

‘The current generation has seen the incentives for loyalty slowly being eroded: loss of final-salary pension, removal of increments from the new junior doctors contract, below-inflation pay rises, etc. These doctors also don’t like the training environment across medicine broadly that has been present during the past 10 years.

‘To coin a phrase, they want to “take back control” of how they work and that’s easier as a GP than as a hospital consultant. Control also explains why partnership is still attractive.’

And Dr Ben Rusholme, a GPST1 in Winchester, is typical of trainees when he says: ‘I may take my time to find the right practice, but partnership is my destination. I want an equal voice in the development of the practice.’

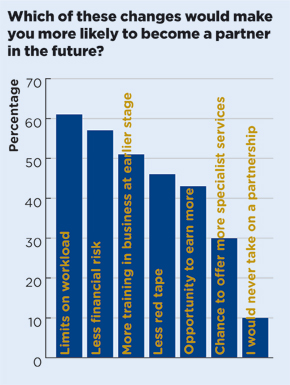

There are obvious ways to attract even more new GPs towards partnership. Almost two-thirds of trainees (61%) said limiting workload – such as placing a cap on the number of appointments – would make them more likely to become a partner in the future. The second-most welcome change would be mitigating the financial risk involved, such as premises commitments, which 57% of respondents said would make partnership more attractive.

Trainees’ career intentions

Interestingly, the opportunity to boost earnings came lower down the list – behind better training in business and less bureaucracy.

becoming a partner 290x385px

And the view that full-time partnership may be unsustainable in the long term is held by a growing number of their older colleagues. As Pulse revealed last year, partners in some areas of the country – including Hampshire, Wolverhampton and Somerset – are giving up their contracts to work in salaried positions at trusts in a bid to lessen pressure and burnout.

A Pulse survey in April last year found more than half of partners would consider going salaried if offered the right deal. And official NHS workforce statistics showed a 20% increase in GP locums last year.

These latest findings suggest that there is a new generation of GPs who are aware of the problems in the profession, but are determined to modernise the partnership model by their individual actions, finding a solution to the problem of burnout by varying their careers and spending less time in the consulting room.

As Dr Duncan Shrewsbury, chair of the RCGP Associates in Training Committee, puts it: ‘The results of the survey illustrate the diversity within the profession. For many, the vision of a career in general practice now and in the future combines a variety of complementary roles that our training and experience enables us to engage with.

‘I would even go as far as to suggest it is encouraging to see people thinking of engaging in sustainable ways of working in general practice in the future.’

The partnership model is not dead – but the next generation of GPs will reshape it in their own image.

The part-time profession?

Health Education England chief executive Professor Ian Cumming angered trainees in June by claiming full-time equivalent (FTE) GP numbers were down because ‘Generation Y and Z and millennials are increasingly not wanting to work the same number of hours that many of the baby boomers and Generation X want to work’.

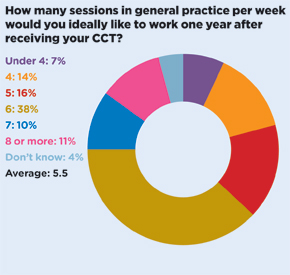

Pulse’s survey reveals trainees want to work 5.5 sessions a week – far less than the eight sessions hitherto considered a full-time GP role.

But Professor Cumming failed to say that this does not mean the next generation of GPs will be working any less hard than their older peers.

While it is true the next generation want to ‘take back control’ of their working lives – the most popular reason cited in our survey for choosing general practice was ‘work-life balance’ and 16% cited ‘flexibility or control over working hours’ – they are still likely to work in other areas of the health service.

The option of a portfolio career was chosen by 15% of GP trainees as their main reason for choosing general practice. And this suits the direction of a health service that increasingly wants its GP workforce to work in other areas, such as A&E or in CCGs.

Dr Zoe Greaves, a GPST1 in north-east England, typifies the portfolio approach. She has worked as a public health trainee and plans to take on a partnership at some point.

She says: ‘I enjoy clinical work, but have seen colleagues burn out doing it five days a week. I feel more challenged and engaged with my work when I have variety to my week, and am passionate about improving and developing the way we deliver services.

‘I would want the opportunity to continue to use and develop the skills I’ve gained alongside clinical work.’

And as every practising GP knows, the complexity and intensity of general practice consultations are only going to increase. Even experienced doctors now question whether an eight-session week is desirable, or even safe.

And the benefits of full-time general practice, such as seniority payments and final-salary pensions schemes have diminished, alongside real-terms pay cuts over the past decade. So it may not be that new GPs ‘want to work less’, there is just no incentive to work more.

Of course all this could have a profound effect on the wider profession. HEE’s target to train 3,250 new GPs a year – an objective already put back two years – may prove insufficient to supply the 5,000 extra FTE GPs promised by the Government. And some estimate double this number are needed anyway.

The upshot is that either we need to persuade the current generation of trainees it is in their interests to work more sessions in general practice, or we have to find other ways of meeting ballooning demand on GPs’ time.

Click here to read all the news, views and advice articles from our month-long special on GP training

Reference

1 Wessex LMCs, 2014. Newly qualified GPs share their thoughts. tinyurl.com/wessex-trainees

Pulse October survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens