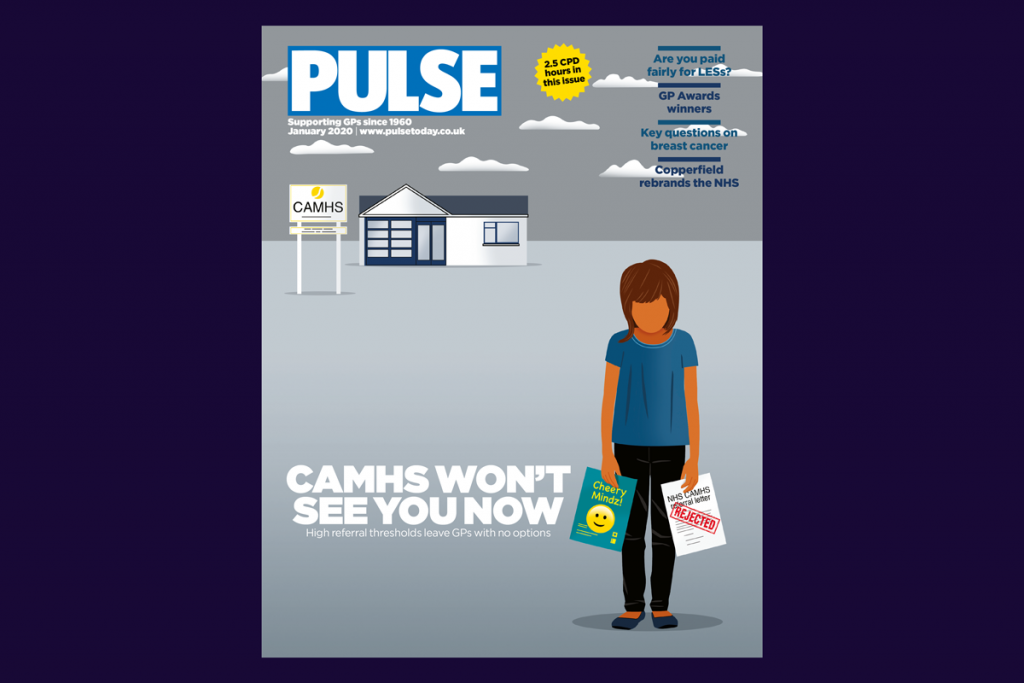

It seems like a lifetime ago now, but back in January Pulse revealed worrying statistics about children’s mental health.

In an exclusive investigation, we uncovered a trend in numbers of referrals to child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) in England, with one third (34%) of trusts only accepting patients whose conditions were categorised as ‘severe’ or ‘significant’.

According to data collected from 29 mental health trusts, just six (21%) accepted referrals for patients with all severities of conditions – mild, moderate, and severe. A further 13 (45%) took referrals for patients who were moderately or severely unwell.

The increased threshold for accepting referrals from GPs flew in the face of evidence suggesting children and young people were facing a mental ill health epidemic. In fact, NHS Digital data showed that referrals to CAMHS rose 18% between 2017/18 and 2018/19.

The disparity between referrals made and accepted meant many children and young people were neglected, leaving their mental health to deteriorate.

Some had even attempted suicide after being rejected by CAMHS, GPs told us, in a bid to be considered ill enough to get specialist help.

Among the young victims whose mental illness didn’t meet local CAMHS’s threshold was 16-year-old Sam Grant. He died by suicide in October 2019, after his GP’s referral was rejected by services in Milton Keynes because they deemed Sam’s symptoms were not ‘moderate to severe’.

Sam’s death, and a subsequent report by a coroner calling for gaps in local mental health provision to be closed, highlighted the tragic real-life cost of budget cuts.

In the wake of Pulse’s investigation, the BMA published a report urging NHS England to implement a ‘minimum investment standard’ for CAMHS. Such a measure, the BMA said, would stop CCGs from redirecting money intended (and needed) for young people’s mental health into other areas.

However, a year after the Government’s 2015 pledge to invest £1.4bn into child mental health services by 2020, CCGs had only seen £75m of the £250m they’d expected in that first year.

The BMA’s January report acknowledged that Government commitments for mental health – specifically around workforce – were likely to fall short, arguing that adequate funding was needed to enable CCGs to double its mental health spending over the term of the NHS long-term plan.

It added that a minimum of 11% of the total health budget should be allocated to primary care – up from 8.1% at the time. That would enable mental health workers to be based in general practice, and might help ease some of the ‘significant pressure’ CAMHS was under.

CAMHS wasn’t alone in feeling the strain, according to a workforce survey the BMA released alongside its report. Across all areas of mental health services, workers reported they were at ‘breaking point’ due to ‘desperate shortages’ of staff.

Of course, if things looked gloomy for the nation’s mental health back in January, they were about to become monumentally worse thanks to the enormous impact of Covid-19.

And – as if a reminder were needed – we’re all still counting the cost.

Pulse July survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens

Hang on – there are some sinister implications lurking in there!

CANMHS is not a primary care service, it is a specialist service, and should be funded fromt he secondary care service budget : to suggest it should sit in primary care is to trivialise the problems these children and families face, and leave a massive hole in the severely stretched primary care budget.

Hospitals should be investigated by the ombudsman for failing to fund and provide this specialist service as a resource and support to primary care within their secondary care budgets.

Perhaps we should look more at why more and more young people are becoming mentally ill?