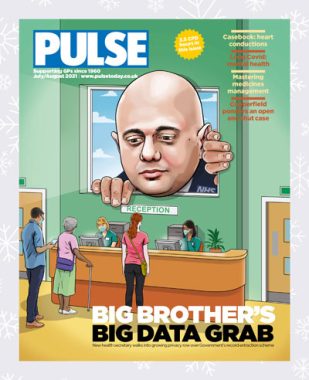

2021 Review: The Government’s failed data grab

In summer 2021, GPs and patients alike were aghast to learn of a new record extraction scheme. In our latest review of the year, Allie Anderson explains all

It can be no coincidence that the acronym for the NHS’s latest scheme to harvest patients’ confidential data – GPDPR – is almost identical to that of legislation designed to protect that confidential data, GDPR.

The great patient data grab, or General Practice Data for Planning and Research (GPDPR), was announced at the beginning of summer and will see patient data records extracted from practices and sent to NHS Digital, from where it will be packaged and sent to third parties.

The revelation left patients and GPs alike bamboozled. For starters, the EU legislation of a similar-sounding name – the General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) – is supposed to make it easier to understand how our private information is used, and by whom.

Yet the ‘patient data for sale’ debacle seems to directly contradict this.

Under the scheme, practices must notify patients about the plan, and then take responsibility for opting out any patients who request it both before the data grab started and at any point thereafter. Unlike the care.data fiasco of a few years back, failure to opt out would mean NHS Digital would take all historic personal data, and this could not be reversed.

The original opt-out deadline of 23 June – which gave patients around a month to withdraw consent – was delayed until September after the plan caused an almighty outcry.

One of the chief concerns was that nobody had been clear about where extracted data would go, who might buy it, and for what purpose.

Importantly, patient information is to be pseudonymised rather than anonymised.

Confidential data like names, NHS numbers and dates of birth will be replaced with unique codes, but NHS Digital itself said this could be reversed so a patient could be identified ‘in certain circumstances, and where there is a valid legal reason’.

It’s unclear what might constitute a ‘valid legal reason’, and the system could be open to abuse.

However, possibly an even greater problem is that the plan might erode patient trust of GPs, at a time when that relationship is already fragile.

Some have suggested patients, worried about privacy, will be less willing to come forward with health concerns.

Even though GPs are not mandating the data extraction – indeed, many want no part in it – the scheme has ‘GP’ in the name, which might suggest to patients their family doctor is complicit.

In the event of any mistakes – for example, a patient opting out but their decision not being processed, or a data leak happening – it’s not difficult to predict who would be on the receiving end of patients’ wrath.

In a positive turn of events, the plan’s start date of September 2021 was further delayed in July.

At the time, health minister Jo Churchill announced that a universal start date would not be set and that data would only be shared if three criteria were met.

They are: patients’ ability to opt out and back into data sharing, and being able to have data deleted even after it’s uploaded; the assurance that de-identified data will be processed by approved researchers in a trusted research environment; and increased public awareness of the programme to ensure patients know their choices, and how their data will be used. As of now, there is no indication when it will be revisited.

Even with these caveats, some might be concerned that this whole situation is simply the return of the doomed care.data fiasco, which was dropped in June 2016.

The cost to the taxpayer of that plan was an estimated £8m. It’s unclear what the bill will be for this latest Big Brother big data grab.

But after the horrors of the last couple of years, for general practice at least, it could be severe.