Primary care in the age of AI

As part of the Pulse in Print series looking at the past, present and future of general practice, Dr Annabelle Painter and Dr Patricia Schartau look at how AI could help primary care – and hinder it

Artificial intelligence (AI) is the latest buzzword in the healthcare sector. The technology has been deployed in various healthcare settings, and primary care is no exception: according to the 2022 Health Education England roadmap report, the specialty will be one of the top three affected by AI.1 Several AI tools are already widely used in NHS primary care applications, such as triage, arrhythmia detection and skin image interpretation.

However, discussions about the introduction of AI in medical settings are often polarising. Hopes that AI could support more efficient, accurate and personalised care are matched by fears that it could replace health professionals and erode the doctor-patient relationship. This has only been heightened by the recent development of ‘large language models’ (LLMs), algorithms that perform natural language processing tasks. It is LLMs that are behind chatbots such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Google’s Bard, which have sparked both excitement and concern in the medical community.

The term AI does not just refer to chatbots, though – it covers a broad range of technologies. The heated discussions about its impact often do not reflect the actual technology being deployed in primary care. Here, we take a look at how medical AI products could help and hinder general practice in the future.

What is AI?

There is no universally agreed definition of AI, but we will use the wording provided by the NHS: ‘The use of digital technology to create systems capable of performing tasks commonly thought to require human intelligence.’7

This definition encompasses a wide range of technologies in a primary care setting, including many that are already in use, such as risk score calculators and the automated reports on ECGs. It also covers technologies that have been implemented in primary care more recently, such as image interpretation tools and heart rhythm detection using smart watches or smart stethoscopes.

How AI can help primary care

1. Admin tasks. One of the biggest initial impacts that AI is likely to have is assisting with automation of administrative tasks. Survey data suggest that GPs spend an average of 12.8% of their time on clinical paperwork2 and predict that almost half of the admin tasks in GP surgeries could be automated.3 Meanwhile, 80% of surveyed GPs believe technology could fully replace humans to undertake documentation.4

Although we are not there yet, AI is already able to support a GP’s administrative duties: it can do everything from transcribing consultations and creating clinical notes to writing referral letters. At systems level, the technology can be used to optimise resource allocation by predicting demand, scheduling appointments, issuing reminders and recalls, as well as registering new patients.

Furthermore, recent advances in LLMs have improved AI capabilities in summarising and translating large volumes of textual information. In primary care, this can be applied to summarising patient health information, which could be useful now that practices in England all have to offer patients automatic online access to their GP health records. The translation of the clinical jargon and abbreviations within patient records into patient-friendly terminology would be a task well suited to LLMs.

In addition, LLMs can be used to support virtual receptionists to help patients navigate the healthcare system, access information and submit administrative requests to practices. Current products include:

- Microsoft Nuance: enables clinicians to record consultations and create notes via Teams.

- BetterLetter: annotates and codes clinical letters.

- EBO.ai: handles patient requests through a chatbot.

- Vital.io: translates technical medical terminology into plain language.

2. Supporting clinical decision-making. AI tools can augment clinical decision-making, improve diagnosis, and support treatment decisions and patient monitoring.

Automated triage is a growing area for AI in primary care. Before the pandemic, many practices were already using some form of patient triage to manage their appointment load. But AI tools are increasingly being used to automate the process. By assessing symptoms, severity and urgency, these systems aim to reduce waiting times and improve service navigation. Effective triage could optimise the allocation of resources and ensure patients are seen by the right member of the primary care team at the right time. Based on triage assessment, patients may be directed to book appointments with a nurse, physician associate, practice pharmacist or a GP, or signposted to self-referral MSK services, talking therapy services or their pharmacy. Patients with an emergency may be advised to call an ambulance or attend A&E.5

Decision-support tools in primary care also include image analysis, specifically for skin lesions. These tools can help support clinicians in making referral decisions to secondary care for suspected skin cancers. This is just one example of an AI-enabled pathway that is being expanded across GP practices.6 Such AI-first pathways may be of particular benefit in rural settings to facilitate faster diagnosis without making the patient travel to a specialist appointment. Other analytic tools can assess otoscopy images, diagnose arrhythmias and heart failure, or measure vital signs through tablets and smartphones.

Meanwhile, an AI-enabled search of clinical guidelines can help clinicians access relevant information quicker. Integrating this functionality with patient health records could enhance the value of these tools by prompting clinicians with suggested personalised investigation and management plans. Assisted prescribing, which is integrated with patient records and implemented in primary care, provides a real-time decision-support tool to optimise prescribing practices in terms of safety and cost-

effectiveness. Products include:

- Healthily, Visiba Care, Klinik, eConsult: AI patient triage.

- Medwise.ai: AI-enabled search of clinical guidelines for primary care.

- Skin analytics: AI-enabled interpretation of dermatoscopic skin images.

- Alivecor Kardia device: AI-enabled detection of arrhythmias.

- Eko Duo smart stethoscope: AI-enabled arrhythmia and heart-failure detection.

- Lifelight: remote vital signs monitoring, taking blood pressure, pulse and breathing rate readings in 40 seconds, just by a patient looking into a smartphone or tablet.

- ScriptSwitch: prescription tool.

3. Assisting patients. Products such as wearable devices, disease-monitoring tools and AI-powered home-testing kits are being used to support patients in detecting and self-managing medical conditions.

Patient-facing AI tools may be prescribed by healthcare professionals and incorporated into clinical pathways to aid in diagnosis or management of conditions. Other tools are marketed directly to patients, who may ask health professionals for advice in interpreting their results, or for a second opinion. In both situations, there is a key question – who carries responsibility if AI-based decisions lead to poor patient outcomes? This is an ongoing debate.

Examples of patient-facing tools embedded in clinical practice include AI digital therapeutics such as AI-powered health-and-wellbeing coaches and mental health chatbots, which can deliver therapies including CBT.

AI tools for chronic-disease management are another area of growth. By analysing patient data collected from wearables, electronic health records and other sources, AI can detect trends, identify potential exacerbations or complications, and provide personalised interventions or reminders to patients for medication adherence and lifestyle modifications.

AI tools marketed directly to patients include smartwatches and other wearable devices such as earphones and rings that can continually measure vital signs like heart rate, oxygen saturations and body temperature. The Apple watch and FitBit watches contain CE-marked atrial fibrillation detection algorithms. Continuous glucose monitors are being marketed directly to patients to monitor their blood sugar levels and inform lifestyle choices. These include the Zoe app, which uses a CGM and microbiome analysis to give individualised dietary advice. In women’s health AI, ‘femtech’ products such as menstrual cycle trackers, sometimes with temperature monitoring by wearables, are increasingly being used as contraception and conception aids.

Health professionals are likely to be asked by patients about the outputs of these products and will need to develop an understanding of them, their limitations and how to incorporate them into care pathways and clinical decision-making.

How AI can hinder primary care

As with all technologies, AI is not transformative in itself. It is a tool to enable meaningful transformation. The key determinant of the technology’s success is effective implementation.

Education will be central to ensuring healthcare professionals are able to use and interpret AI tools appropriately and support patients. This is particularly relevant for LLMs. While they are unlikely to be certified as medical devices in the short term, the prevalence of ChatGPT means healthcare professionals and patients are already using these technologies for medical purposes despite known issues with accuracy and bias. It is important to know how to address information of uncertain accuracy that patients have obtained via LLMs.

There is also a question mark about the readiness of the IT and data infrastructure in primary care to allow interoperability. Health equity, digital exclusion, bias, fairness and data security are also important ethical topics to be considered. Building trust in AI tools for patients and clinicians is a significant challenge.

Concerns about over-reliance on AI outputs and clinical deskilling need to be addressed. It will be essential to maintain alternatives to AI-enabled pathways to mitigate risks and avoid digital exclusion.

The future?

While most healthcare professionals believe it unlikely that AI will replace clinicians, it might transform the clinician’s role to that of a translator and adviser who works with patients to distil complex information and produce personalised management plans based on AI-derived insights. The hope is that the time released can be used to strengthen clinician-patient relationships. However, there is a risk that the time is instead used for more patient throughput. Adapting to new ways of working will be a growing challenge, requiring education at all stages of a medical career. Educational initiatives for professionals and patients will be key to promote ethical AI adoption and informed decision-making. Clinicians may not be replaced by AI, but they risk being replaced by clinicians better able to use it.

Dr Annabelle Painter is an honorary fellow in digital health at Imperial College and a GP registrar in London, and Dr Patricia Schartau is a lecturer in primary care at UCL and a GP in London

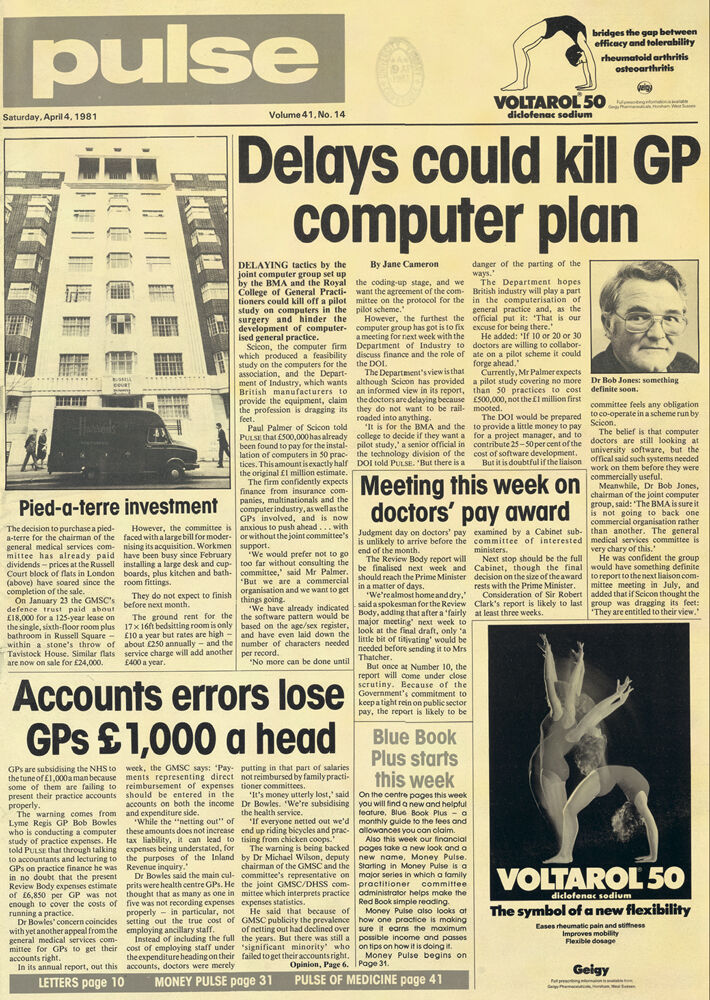

In June 1981, the very concept of computers in surgeries looked highly unlikely. A £1m scheme to put computers in 50 practices was being delayed because, as the Department of Health put it, ‘the profession is dragging its feet’

References

1. NHS Health Education England. AI Roadmap Methodology and Findings Report. January 2022. Link

2. Sinnott C et al. Identifying how GPs spend their time and the obstacles they face: a mixed-methods study. BJGP 2022;72 (715): e148-e160. Link

3. Wills M et al. Future of Healthcare: Computerisation, Automation and General Practice Services. Oxford Martin School. June 2020. Link

4. Blease C et al. Computerization and the future of primary care: A survey of general practitioners in the UK. PLoS One 2018;13(12):e0207418. Link

5. RCGP. The future role of remote consultations and patient ‘triage’. 2021. Link

6. NHS Royal Devon University Healthcare. Skin Analytics / AI Pathway Information. September 2023. Link

7. NHS England. Definition of artificial intelligence. February 2023. Link

Pulse October survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens