Pulse in Print: How issues around race came to the fore in the 2010s

In the final piece looking at the biggest stories during Pulse’s time in print, we look at two stories in the last decade that highlighted racial issues within medicine

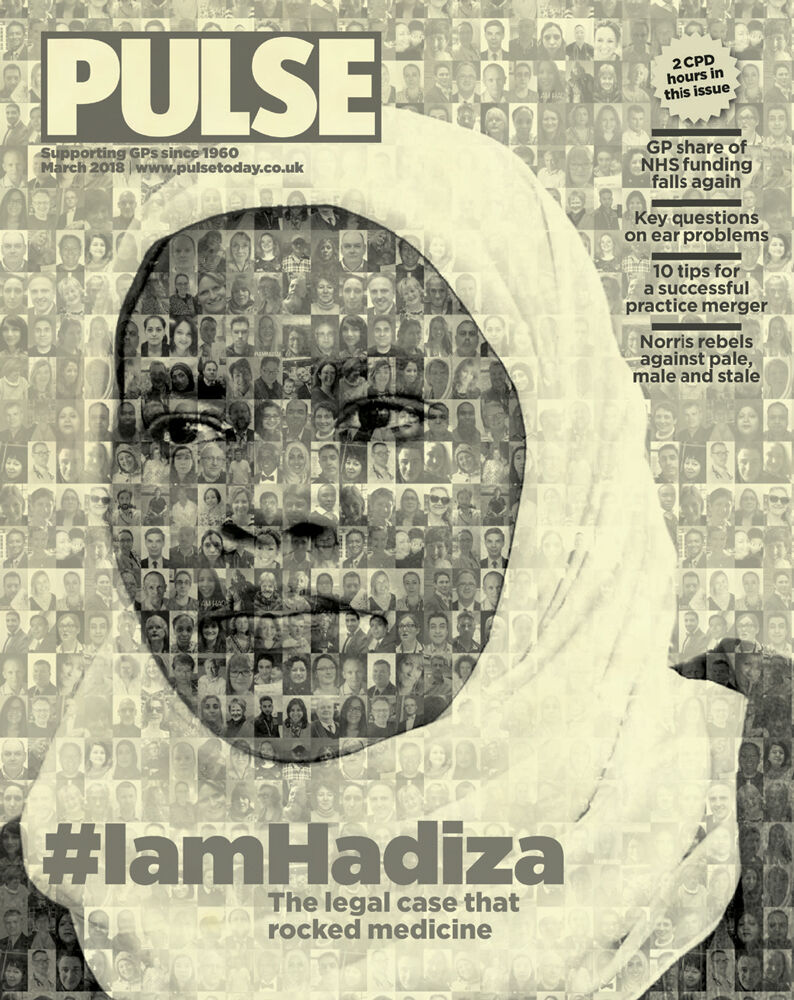

‘Sometimes images are more powerful than words and that was the case for this cover story. I wanted to visually represent the strength of feeling and solidarity among doctors over the treatment of Dr Bawa Garba, the junior doctor hauled through the courts by the GMC over the death of a young boy. In particular, it was the sense that “it could have been me” that many GPs expressed to us. In the end we managed to use the images of 141 different GPs that made up the portrait of Dr Bawa Garba. It was a simple device, but incredibly powerful, and I know was greatly appreciated by Dr Bawa Garba herself, as she was going through such a hard time. It was classic Pulse: hard-hitting, incisive and perfectly representing the feeling in general practice.’ Nigel Praities, Pulse editor 2013-2018

The case that shook the profession

When it comes to medical regulation, few events caused shockwaves through the profession as large as the case of Dr Hadiza Bawa-Garba. And they can still be felt today, more than a decade after the story began.

In 2011, Dr Bawa-Garba was a paediatric trainee who had just returned from maternity leave. She was working on the children’s assessment unit at Leicester Royal Infirmary, and due to staff shortages she was the most senior doctor there. There was no dedicated consultant, agency staff were covering nursing shortages, and IT problems meant tests were not getting through.

Against this challenging backdrop, mistakes led to the tragic death of six-year-old Jack Adcock. He had sepsis, but due to delays in reviewing his X-rays and blood results, Dr Bawa-Garba didn’t pick this up soon enough. At a coroner’s hearing two years later, she admitted that she was ‘not on top of things’.

The Crown Prosecution Service had initially decided not to pursue any case. However, this decision was overturned based on evidence from the coroner’s hearing. At the end of 2015, Dr Bawa-Garba was prosecuted for gross medical negligence manslaughter and given a two-year sentence.

But her troubles did not end there. The Medical Practitioner’s Tribunal Service (MPTS) had dismissed an appeal from the GMC to have Dr Bawa-Garba struck off, but in 2017 the GMC took the astonishing decision to challenge this verdict at the High Court. The regulator defied its own tribunal service. And the High Court agreed – the junior doctor was struck off in January 2018.

This did not go down well with the medical profession – the backlash was instant. Doctors worried that one clinician could be held solely responsible amid a backdrop of systemic failures. GP and BMA chair at the time Dr Chaand Nagpaul said many doctors now feel the NHS has a ‘culture of fear, blame and defensiveness’. And the British Association of Physicians of Indian Origin (BAPIO) said ‘inherent bias’ against BAME doctors lay behind the GMC’s decision – a claim which the regulator rejected.

The case resonated profoundly with GPs, who are no strangers to workload and system pressures. In fact, following the case, Pulse heard from many GPs who feared this could have been them, resulting in the powerful ‘I am Hadiza’ hashtag.

But it wasn’t just doctors who seemed worried about the precedent this case set. Former health secretary Jeremy Hunt announced a review into the use of gross negligence manslaughter charges in medicine which concluded that the GMC should no longer be able to appeal decisions made by its own MPTS. But after five years, the necessary legislation is still pending. And within that time, the regulator has launched 24 appeals against its tribunal’s findings.

The strength of feeling among the profession did lead to tangible change. Dr Bawa-Garba was able to appeal the High Court’s decision after £350,000 was raised through crowd-funding. In August 2018, the Court of Appeal restored the original MPTS decision that she should be suspended rather than erased. And in 2019, the MPTS ruled that she could return to practice under certain conditions.

More broadly, the GMC has made efforts to change and apologised for the distress caused to the medical profession. The regulator has updated its fitness-to-practise processes to include training on ‘human factors’. In 2019, a report looked at why BAME doctors are subject to disproportionate referrals, and two years later the GMC promised to ‘eliminate’ this inequality by 2026.

Last year, however, the infamous ‘laptop’ case threatened to undo these positive strides. GP Dr Manjula Arora – another BAME GP – was suspended for two months for ‘dishonesty’ after telling her IT department that she had been ‘promised’ a laptop. The tribunal found she had ‘exaggerated’ these claims. All too familiar backlash ensued – the BMA said this decision was ‘incomprehensible’. Reacting quickly, the GMC launched a review into the decision and effectively overturned it by saying the dishonesty test had been ‘incorrectly applied’.

Despite the GMC’s willingness to admit its failures in this case, distrust among GPs and the wider medical profession hasn’t gone away. Over the summer, the BMA passed a vote of no confidence in the GMC based on its handling of referrals.

And concrete inequalities remain. The latest data shows that although the gap in referral rates between ethnic minority doctors and white doctors has reduced, there is still a notable difference. In the five years up to 2022, 0.41% of ethnic minority doctors were referred compared with 0.22% of white doctors.

Beyond the figures, doctors continue to raise concerns about new referrals and MPTS rulings against international medical graduates. The GMC still has a long way to go – not just to eliminate inequalities, but also to rebuild trust with an increasingly cynical profession.

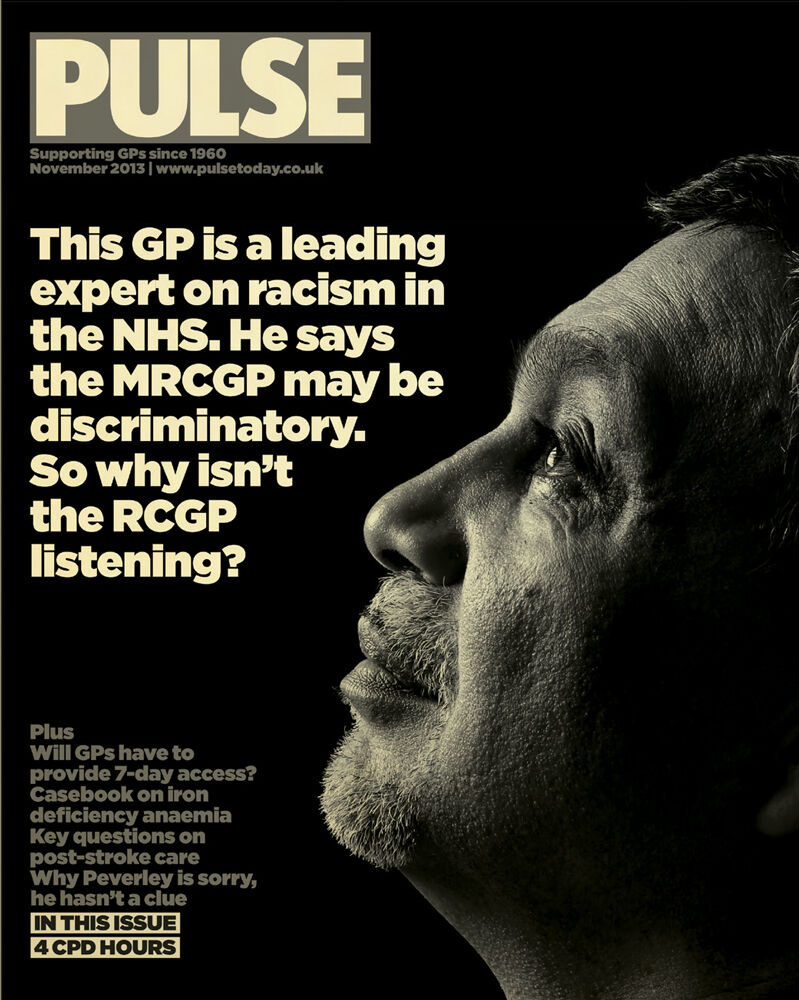

Row over RCGP exams hits the courts

‘I remember this story well because it was the cover story in one of the first couple of Pulse editions after we switched from weekly to monthly publication. The new monthly magazine format opened up the opportunity to delve deeper into topical issues and we were proud of the innovative way we used the feature-style cover to add impact to our coverage of such an important story. It still jars somewhat to recall the RCGP’s response to new evidence of potential racial bias in the CSA part of the MRCGP exam. I remember our shock when The BMJ told us they had received a letter from the college’s lawyers demanding deletion from a press release and academic paper of Prof Aneez Esmail’s conclusion that “subjective bias due to racial discrimination” may have been a cause of the disparity in exam pass rates.

‘Thankfully the last decade has seen an important and growing focus on diversity and inclusion in all professional sectors and it’s hard to imagine the college would react so defensively to a similar controversy today. It would be nice to think that stories like this one played at least a small part in raising the profile of an important inequality issue. On the other hand, GMC chief executive Charlie Massey’s comments earlier this year that we should be ‘ashamed’ of the lower exam pass rates among trainees from ethnic minority backgrounds suggests there is still a long way to go to solve the problem.’ Jo Haynes, Pulse editor, 2006-2009, Pulse group editor, 2009-2014

In 2012, the Royal College of GPs was facing a huge controversy around its clinical skills assessment component of its MRCGP exit exam, which used actors to simulate consultations at the college’s headquarters. The data showed that international medical graduates were 15 times more likely to fail the exam than British-educated candidates. But even more alarmingly, non-white British-educated candidates were 3.5 times more likely to fail than their white counterparts.

As a result, the college was facing a judicial review brought by the British Association of Physicians of Indian Origin (BAPIO). The accusations against the college centred on the use of actors, especially on their ethnic make up. BAPIO claimed that there was racial bias in these simulated consultations. Pulse broke the story about the judicial review, and led the subsequent coverage. This led to perhaps the low point in Pulse’s relationship with the college.

The GMC commissioned a study into the differentials, led by Professor Aneez Esmail, a GP who had undertaken major work studying systemic racism. When the study was released, the college and the GMC concluded that it largely exonerated the exams. But when Pulse contacted Professor Esmail, a different story emerged. He refuted the two organisations’ readings of the study, and it transpired that he had also written a study for the BMJ based on the same data that concluded ‘subjective bias due to racial discrimination’ may be a cause for the differentials.

But this wasn’t the most explosive revelation. Professor Esmail told Pulse that the college had threatened the BMJ with legal action if it published this conclusion.

The judicial review – which was supported by the BMA – found in favour of the college, but by no means emphatically. The judge concluded that the ‘the time has come to act’, suggesting that a subsequent review may find against the college.

Since then, there have been moves to address these differentials. The CSA no longer exists, replaced during Covid by the Recorded Consultation Assessment, which allows candidates to choose which real-life consultations they submit. This has almost removed the differentials between ethnicities, if not between UK-graduates and IMGs. Around 99% of white British graduates passing the exam and 95.5% of non-white graduates passing. Even among IMGs, it was healthier – 82.9% of white graduates passing compared with 79.7% of non-white graduates.

However, this exam has been replaced by the simulated consultation assessment in November 2023 – an exam that uses remote consultations but patients are played once again by actors, making it closer to the CSA. If the results lead to greater differentials, it may not be the last we see of this story.