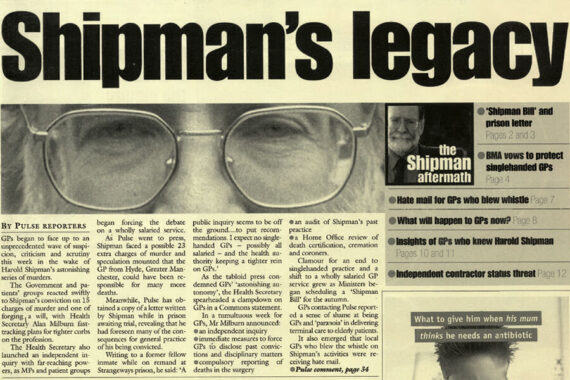

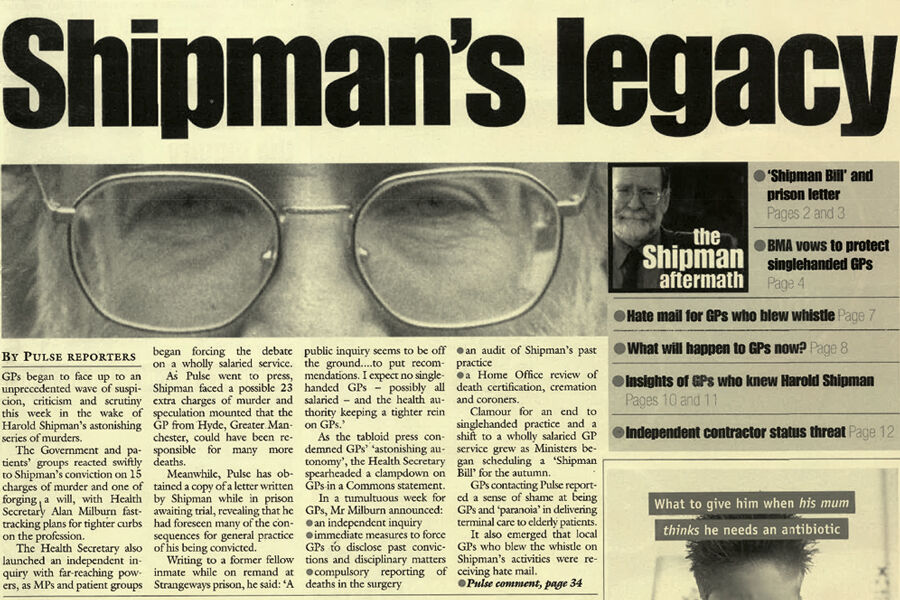

Pulse in Print: The Shipman legacy

As part of the Pulse in Print series, we review the consequences of Harold Shipman, the monster who has had a bigger effect on general practice than maybe any other GP

A short story on page 4 of the 19 September 1998 issue of Pulse was the first mention of the monster who sadly became one of the most consequential GPs in history. It’s still not clear how many patients Harold Shipman murdered, but the total is at least 212 and estimated to be around 250.

It is a cliché that you can never tell, but in Shipman’s case it seems to be true. His popularity as a GP might have been overstated – Dame Janet Smith’s inquiry into his killings said he was ‘well liked by patients’, but also found ‘many people regarded him as arrogant and “prickly”’. He was a member of the LMC, he was described as smart, organised, an ‘old-fashioned’ GP who would call in on patients while passing. But GPs started raising concerns about the death rates at his single-handed surgery, which the police failed to take seriously enough.

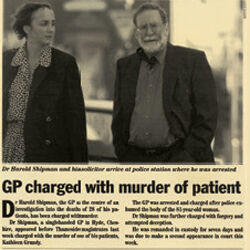

He was found guilty of the murder of 15 patients in February 2000. He hanged himself in his prison cell in 2004.

In terms of the effect of this case on general practice, there were only a few direct ones. Strangely, the most commonly thought effect is a misconception. Revalidation was planned from before Shipman had faced trial, with a consultation document introduced in 2000 (and conceived years beforehand).

Dame Janet Smith’s recommendations led to changes to the recording of death and cremation forms, the complaints procedure against GPs and the regulation of controlled drugs.

There have been less tangible – but no less important – effects, too. Last year, Baroness Finlay of Llandaff, who is a professor of palliative medicine, told an inquiry that doctors are reluctant to prescribe pain-relieving drugs in the correct dosage to terminally ill patients because of the fear of association with Shipman. She further claimed it has had an effect on the debate around assisted dying.

Even less tangible are potentially the two biggest implications for GPs. First is the growing mistrust in GPs. Although the current relationship between GPs and patients has a number of causes, trust began to fall in the aftermath of Shipman. This attitude would no doubt have changed regardless –the concept of ‘doctor knows best’ would be unthinkable now with or without Shipman. But his name is still brought up in any debate on regulating GPs.

The second is the attitude to small practices. In the immediate aftermath of his court case, much focus was on the future of single-handed practices. Indeed, in a 2000 letter by Shipman to a fellow inmate, obtained by Pulse, he wrote that he expected a public inquiry to recommend the end of single-handed practices. He was wrong – Dame Janet Smith explicitly concluded that she didn’t want to see an end to single-handers. But there has been a huge reduction in the number of single-handers – a trend encouraged by NHS managers.

Although Shipman is the name people remember, perhaps we should take time to remember the name of Dr Linda Reynolds, who first raised alarms about comparative death rates between his practice and her own Brooke Practice and doggedly pursued her cause – an action that could have cost her her career. Despite providing evidence, she was ignored by the police, who were criticised by Dame Janet Smith for doing so. She sadly died aged 49 of cancer the same year Shipman was jailed. But she is far more indicative of the profession, and should be remembered as such.

Pulse July survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens