Pulse 2018 review: The fallout from health awareness campaigns

pulse october 2018 final cover 2

No GP would disagree that health awareness among patients is a good thing. Becoming familiar with health risks – and taking responsibility for them – empowers people to improve their own wellbeing, and that ought to ease pressure on health services.

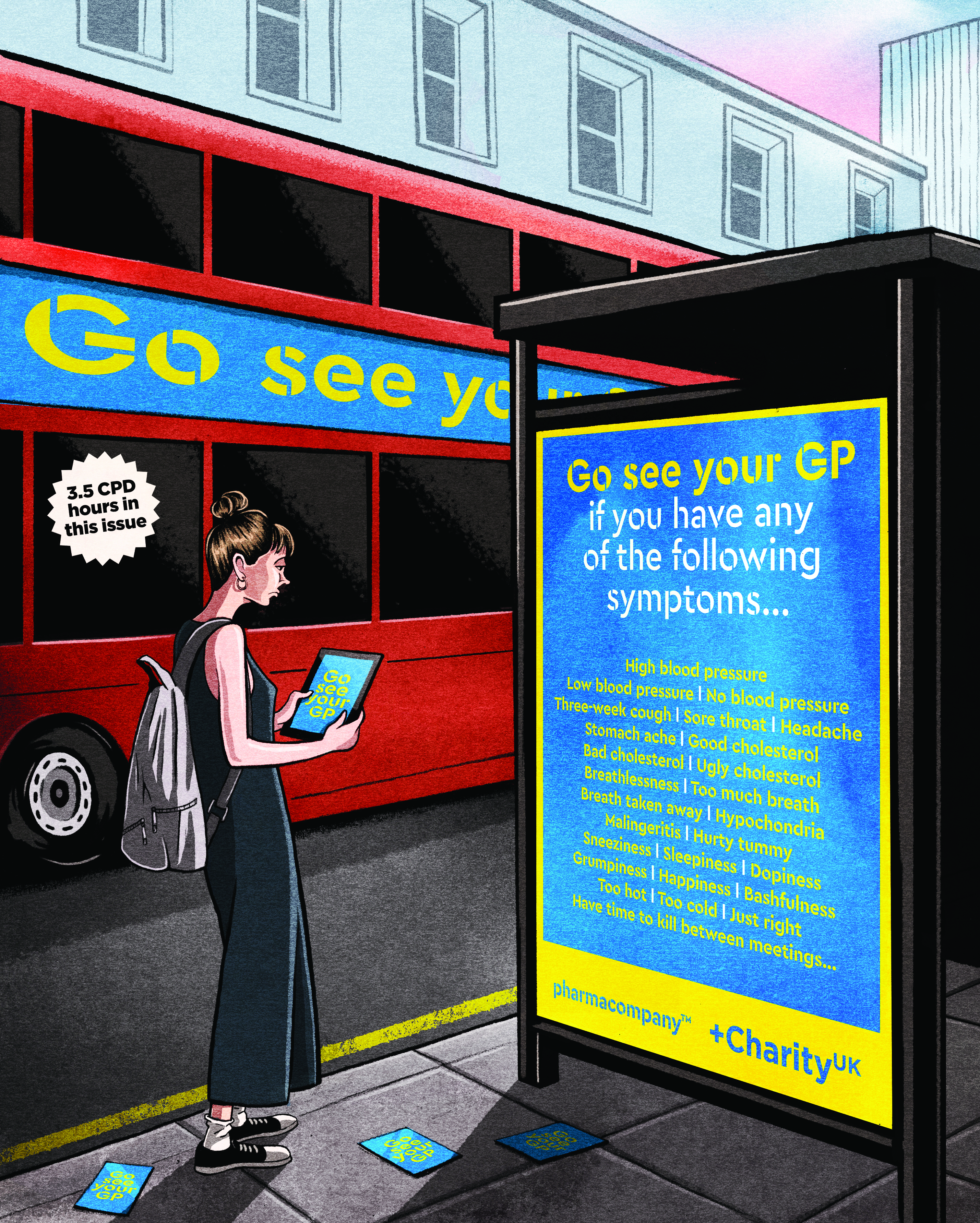

But when misguided health awareness campaigns encourage typically healthy patient cohorts to visit their GP at the drop of a hat, the very opposite can happen.

Enter Public Health England’s heart age campaign.

Throughout September, PHE ran its campaign urging people aged 30 and over to complete an online test to calculate their ‘heart age’ and their lifetime risk of having a heart attack or stroke. The tool calculated a person’s risk based on a set of parameters, according to their answers to a series of questions about their health.

However, people who simply didn’t know their cholesterol or blood pressure were urged – in bold, red letters – to ‘GET TESTED’ by visiting their GP, nurse or pharmacist.

Immediately, alarm bells rang out among GPs.

Their concerns were not that swathes of people would suddenly be diagnosed with thus-far undetected sky-high cholesterol levels and dangerous hypertension. Rather they were anxious that general practice would be inundated with completely healthy patients with no discernible cardiovascular risk factors at all.

PHE said it didn’t foresee that happening, adding that the supplementary advice and resources generated by the tool instead ‘support important lifestyle changes [and] reduces the need for time-consuming prevention discussions with the clinician’.

Experience dictates otherwise, GPs argued, as they steeled themselves to spend time reassuring healthy people they weren’t at risk of cardiovascular disease. The potential knock-on effects on other parts of the system are clear.

Lifetime risk scores have been previously rejected as a valid tool on which to base clinical interventions, due to insufficient evidence and poor methodology.

And, as Pulse revealed in October, despite being fronted by charities, health awareness campaigns are often funded by pharma companies and timed to coincide with the release of a new drug – and not endorsed by the National Screening Committee, which assesses screening success on health outcomes.

As a result, clinical priorities can be wildly distorted.

People begin to worry about risks they don’t have, and more important issues and patients get sidelined. And as always, its GPs who get caught in the middle mopping up the mess.

Pulse October survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens