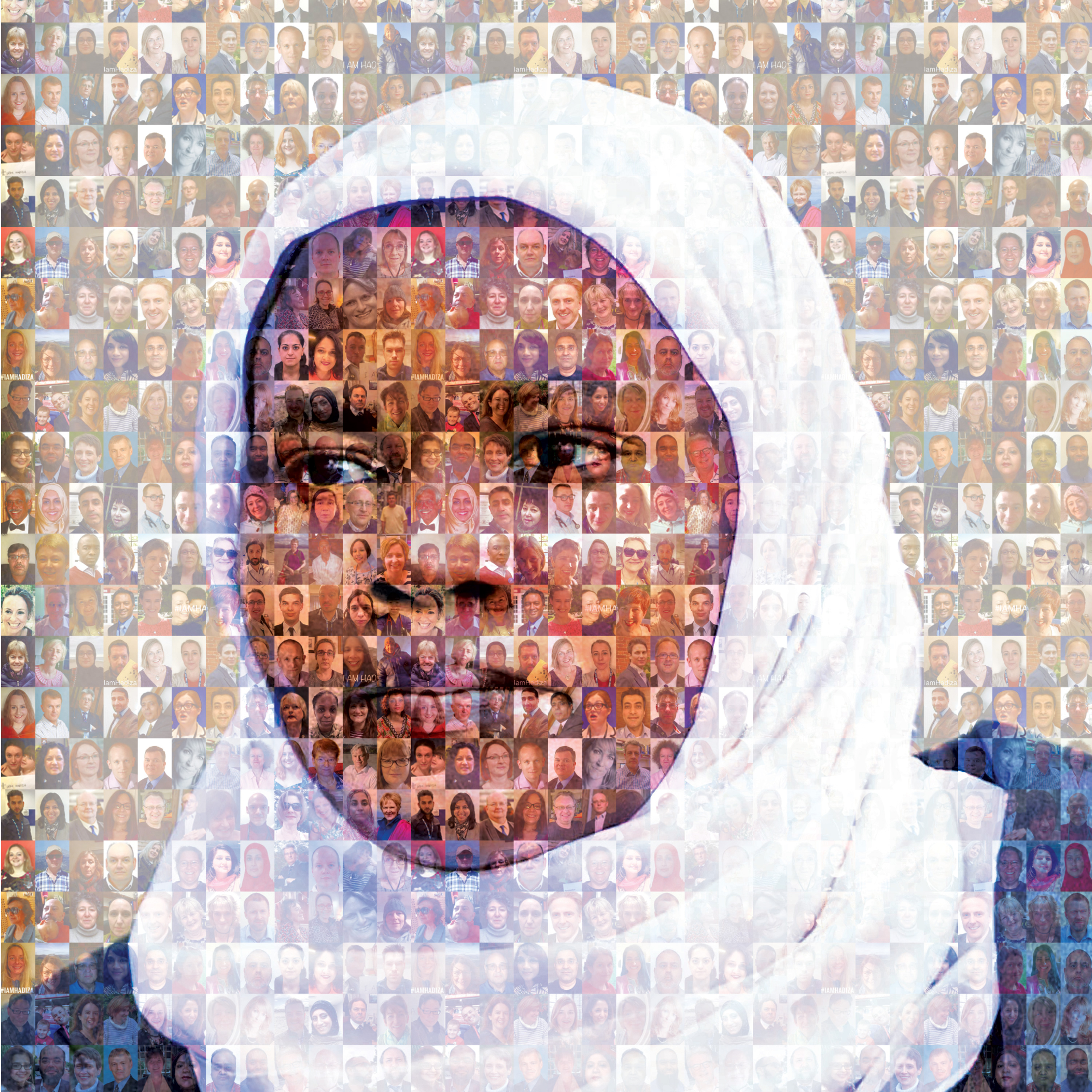

dr hadzia bawa garba mosaic square

The name Bawa-Garba will be long remembered. From the day six-year-old Jack Adcock died in 2011 to when she was accused of medical failings and then found guilty of manslaughter by gross negligence, her case has been a rollercoaster that truly shook medicine.

But after eight years a review hearing finally closed the case: Dr Bawa-Garba has been deemed fit to return to practice from July 2019.

The hearing, which took place on 8 and 9 April, saw the Medical Practitioners Tribunal Service (MPTS) agree that Dr Bawa-Garba’s cumulative suspension has served the public interest and that any higher sanction would be ‘disproportionate and punitive’.

It is the final chapter of a truly tragic case – one in which a 6-year-old boy died. Dr Bawa-Garba had originally diagnosed Jack Adcock with gastroenteritis and failed to spot from blood tests that Jack had sepsis, or review chest X-rays that indicated he had a chest infection.

Initially, it was put down to tragic error. Leicester Royal Infirmary found there had been a number of systemic failings – including staff absences, IT failures and the on-call consultant being unavailable.

But when a coroner ruled that this should be investigated by the Crown Prosecution Service, things changed. It decided that she should face a jury on the charge of gross negligence manslaughter.

Hearing the facts of the case without the context, the jury passed a guilty verdict. Yet the Medical Practitioners Tribunal Service decided that she shouldn’t be struck off, and instead called for her to be suspended.

But – in a move that shocked the profession – the GMC didn’t accept its own tribunal’s ruling, and appealed the MPTS decision in High Court in January 2018. The court agreed with the GMC – and removed Dr Bawa-Garba from the profession.

The GMC’s decision to appeal a decision of its own Tribunal service meant it lost the trust and confidence of many doctors

Dr Chaand Nagpaul

The decision and the GMC’s actions caused uproar. BMA chair Dr Chaand Nagpaul has criticised the regulator for its ‘ill-judged handling of the case’, and has asked the GMC to research whether the public actually expect them to pursue doctors in cases of clinical error following the GMC justification that it needs to maintain public confidence.

Pulse readers sent in stories about when it could have been them. More surprisingly, even former health secretary Jeremy Hunt questioned its handling in a tweet where he said he was ‘totally perplexed that GMC acted as they did’.

The Government even announced its intention to strip the GMC of the power to appeal MPTS decisions. However the GMC has said it will continue until legislation changes.

Dr Bawa-Garba appealed the decision. Her QC James Laddie pointed out at her appeal hearing in July that there were ‘systemic failings which contributed to the environment in which Dr Bawa-Garba came to make the mistakes which led us to this court’. The appeal court agreed, and so her case was put back to the MTPS.

Now, the tribunal has ruled that she can practise again from July 2019 – under supervision – but she does not intend to return to work until February 2020, when her maternity leave finishes. Her fitness to practise remains impaired due to her lack of face-to-face patient contact while she was suspended – a decision that was ‘expected’ according to the Doctors’ Association UK, given the length of time during which she could not work.

The Tribunal decided that Dr Bawa-Garba was could now resume working under close supervision and certain conditions, which will apply for a period of 24 months and include the appointment of a clinical supervisor by her responsible officer or nominated deputy.

There is an irony here. As Dr Nagpaul puts it: ‘The reason for the absence of direct clinical contact for so long is, in part, as a result of the GMC’s actions in the past.’

The case has had a profound effect on the profession. Dr Nagpaul continues: ‘The BMA has always maintained that the GMC should never have been given the right to appeal decisions of its own Medical Practitioners Tribunal Service (MPTS), a right that the Government subsequently deemed the Council will lose. The GMC’s decision to appeal a decision of its own Tribunal service meant it lost the trust and confidence of many doctors and a lot of work is still required to rebuild that.’

Tim Johnson, the law firm that represented Dr Bawa-Garba, agreed about the effect on the profession.

It said: ‘This case has caused enormous controversy. Doctors across the worlds are concerned they too can be convicted of manslaughter and struck off if they make a mistake in diagnosis as Dr Gawa Garba did.

‘Dr Bawa-Garba was not the only person responsible for the death of the patient and the hospital systems broke down that day, which contributed to the mistakes that were made.’

So what happens next? The MPTS said it will conduct a review of the case before the end of her conditional registration to ensure ‘she has made a successful return to clinical practice and that her skills and knowledge are up to date’.

Yet, despite many doctors being relieved that an individual hasn’t had to give up her career due to systematic errors, the debate is now squarely on the environment that allowed the death to happen in the first place, and one doctor take all the blame.

Dr Bawa-Garba was working in appalling conditions that day in an NHS hospital

Dr Jenny Vaughan

A GMC spokesperson says:’We know the medical profession is working under a great deal of pressure and we have been listening to and acting on the concerns which were expressed by the medical profession over this tragic case. Over the last year we have set up a wide programme of work to respond to this and provide support to the profession.

‘We have commissioned independent reviews looking at how gross negligence manslaughter and culpable homicide are applied to the medical profession, why some groups of doctors are referred to us more than others and how medical students’ and doctors’ wellbeing can be protected. We have also worked with others to make sure doctors returning to work after a period of absence feel supported in the workplace and we have produced guidance on reflective practice together with the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges, the Conference of Postgraduate Medical Deans and the Medical Schools Council.

‘We have also introduced human factors training for our staff, which will be delivered to all fitness to practise decision makers, case examiners and clinical experts as part of a collaboration with Oxford University’s Patient Safety Academy.’

But Doctors’ Association UK law and policy officer Dr Jenny Vaughan argues that there are wider learning points – that patient safety might remain at risk unless the current culture of blame within the NHS is tackled.

She says: ‘I’m a patient, doctor and a mother and I know that Jack Adcock should have received better care. However, Dr Bawa-Garba was working in appalling conditions that day in an NHS hospital and all the evidence of what the hospital actually needed to put right was not heard by the jury.

‘There is a culture of blame in the NHS at the moment which, if left unchecked, will mean patient safety is not what it should be as staff will be too scared to admit their mistakes. The next generation of those who want to care will simply vote with their feet.

She adds: ‘It’s right that Dr Bawa-Garba is going to be restored to the medical register as the hospital too was at fault and should have provided better care. We are calling for a just culture so that the system here is made safer as locking up individuals achieves nothing.’

There is still a lot of work that needs be done before clinicians feel safe in their day job and can put this tragic story behind them.