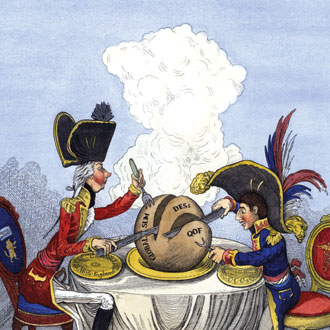

GP contract carve-up: How CCGs are taking control of practice funding

GPs are about to see some radical changes in the way their practice is funded.

All over England, CCG leaders are drawing up plans to take control of directed enhanced services and QOF funding locally. Others are considering radical plans to take control of all GP contract funding by shifting practices wholesale to APMS contracts.

The GPC has warned this could spell the end of the national GP contract, with LMCs describing the potential carving up of practice funding as an ‘absolute, unmitigated disaster’.

And CCGs are doing it at the invitation of NHS England, which has asked them to submit their plans to ‘co-commission’ primary care. The changes could see an unprecedented level of practice income being determined locally – even more so than in the days of PCTs.

The impact on practices is likely to be profound, with the devolution of large chunks of funding giving CCGs even greater sway in the day-to-day functioning of practices. The move has also stoked the old debate over conflicts of interest and performance management.

There have been rumblings about CCGs ‘co-commissioning’ primary care with local area teams since April last year, when CCGs took responsibility for commissioning other health services. But the issue shot up the agenda when Simon Stevens took over as chief executive of NHS England in April, and used his first speech to extol the virtues of co-commissioning.

Speaking on 1 May at the NHS Clinical Commissioners conference in London, he told delegates this would help to ‘properly resource’ primary care. Many CCGs in England submitted proposals on the areas they want to co-commission by the 20 June deadline.

But Mr Stevens has faced immediate opposition. In May, the annual LMCs Conference voted to oppose co-commissioning, with local leaders expressing concerns over conflicts of interest, the threat of CCGs performance-managing GPs and – most importantly – the danger to the core national GP contract.

National contract break-up

Speaking at the Pulse Live conference in Manchester last month, Dr George Rae, chief executive officer of Newcastle LMC and a member of the GPC, said: ‘One of the concerns that I have is about the national core GP contract and conditions and terms of service. I think it would be an absolute, unmitigated disaster if in general practice we moved away from a national contract, and national conditions and terms of service.

‘[Co-commissioning] gives a huge avenue of input into disintegrating that national contract and getting a local contract.’

But CCG leaders point out there is no political will to give GPs a pay rise at a national level, insisting co-commissioning could be a way to plough much-needed money into practices through paying for additional staff and improving premises, among other areas.

‘The future is about how we manage complex comorbidity and the frail elderly’

Dr Matthew Dolman, chair of NHS Somerset CCG and a GP in North Sedgemoor

Moves to carve up the national GP contract have already begun. In Somerset, the CCG has already struck an agreement with the local area team and the LMC for local practices to work to a local alternative to the QOF.

Under the agreement, Somerset GPs will abandon reporting on all but a few key indicators of the QOF – those relating to diabetes, hypertension and COPD reviews – and instead will focus on providing more integrated care through ‘federated networks’.

The local agreement will see practices paid the same amount of money as they would have received under the QOF, and some 80% of practices have already signed up for the rest of this year.

Dr Matthew Dolman, chair of NHS Somerset CCG and a GP in North Sedgemoor, says the plans will help GPs prioritise their work and that quality of care will be maintained.

Dr Dolman says: ‘The future is about how we manage complex comorbidity and the frail elderly in an integrated way with a workforce that is sustainable. This is only a framework, we acknowledge that, but the exciting thing is people can learn from it and use it to develop primary care elsewhere.’

But the GPC has – perhaps predictably – raised concerns that the Somerset deal undermines the national GP contract and will increase instability for practices.

Deputy chair Dr Richard Vautrey says: ‘CCGs have a responsibility to build on the core contract, not to undermine it.’

He adds: ‘There will be expectation that they continue to deliver on the various QOF indicators whether they are being paid directly for them or not, and then will be expected to do even more work on top of that, utilising that existing resource.’

Pulse has learned other CCGs are following suit, with a series of even more radical proposals detailed in their co-commissioning plans, submitted to NHS England last month.

NHS West Hampshire CCG wants to create a giant funding pool formed of money from QOF, directed enhanced services, the £5 per head of population funding designated to support the unplanned admissions DES, as well as money from the ‘Better Care’ fund – a £3.8bn nationwide fund designed to integrate health and social care services.

Related articles

Nine in ten CCGs sign up for co-commissioning as NHS managers pave way for performance managing GPs

Creative funding

The CCG’s clinical vice-chair Dr Nigel Sylvester, a GP in Winchester, says this is a ‘much more creative’ way of using practice funding. He says: ‘If you could pool funds and look at what you could do locally, that is a much more creative way of using the money rather than being straitjacketed by the national requirements.’

Elsewhere, NHS Basildon and Brentwood CCG wants to pilot a model of primary care that will see commissioners take control of all core practice funding through an APMS-style umbrella contract next year.

This will see GP practices working as part of one organisation, involving mental health, acute care and social care professionals specifically to care for frail older people and those with long-term conditions, using joint budgets from NHS England, the CCG and the local authority.

The CCG says the new model would combine ‘elements of core and enhanced primary medical services for a defined population, under the umbrella of a single prime provider organisation, commissioned under an APMS contract’.

Tom Abell, chief officer of NHS Basildon and Brentwood CCG, says: ‘At present, the CCG does not have a mechanism by which we can rebalance funding from the community and secondary care sector to primary care, which I see as an essential tool to secure the sustainability that I, our members and our communities want to see.

‘Co-commissioning may provide us with that opportunity but we will not know this until we have concluded the exploratory conversations with NHS England.’

Controlling GP

‘It’s like being in a yacht club that tells you where to go and what colour to paint your boat.’

Dr Brian Balmer, chair of Essex LMC

But the idea has caused consternation among local LMC leaders. Dr Brian Balmer, chair of Essex LMCs, warns the plans are ‘frightening and extreme’. He says: ‘The CCG wants to take more control of what GPs do.

‘It’s like being in a yacht club that tells you where to go and what colour to paint your boat. If everybody says no then the CCG will just go ahead and do it with a private healthcare provider. They say that they want to pilot a short-term, two-year contract, and this will lead to a salaried service.’

But LMC leaders elsewhere are less negative. Dr Nigel Watson, chair of Wessex LMC, says the LMC can see positive points in their CCGs taking on co-commissioning.

He says: ‘The concept of co-commissioning has opportunities and threats. Our LMC has written to CCGs to say that we think there is value in co-commissioning in terms of CCGs who have a much better idea of their own practices rather than the area team, through peer review, peer pressure and support.’

In the specific case of NHS West Hampshire CCG, the LMC is not against the plans. Dr Watson says: ‘West Hampshire is a good CCG. We work closely with them and they are quite primary care focused. I think they are expressing an interest and exploring opportunities.’

Conflict of interest

Local control of GP funding means practice fortunes will depend much more on the financial health of their local CCG. The latest quarterly monitoring report on NHS finances by the King’s Fund showed that fewer than four in 10 CCG finance leads are confident they will balance the books in 2014/15, and some fear this could lead to practices losing out as CCGs use their funds to prop up other areas.

Another concern is that the move leaves CCGs open to claims they are feathering their own nest. Dr Watson says: ‘When it comes to contractual issues – such as breach notices and performance-management of individuals and practices – CCGs have an absolute conflict of interest. They also do not have the people to do all the functions that the area team does.

‘If you take a CCG where the chair works in a market town, how can you develop services or new premises, or performance-manage a contract if the GP is a neighbour? The conflicts of interest would be just too great.’

But NHS England says conflicts of interest are manageable. Its head of primary care commissioning, Dr David Geddes, says building safeguards in is ‘eminently doable’.

He says: ‘I think that whenever we develop a new service, or we take that process forward with CCGs and NHS England, co-commissioning, we need to manage the conflict of interest. That is really important. It is important for the confidence of the profession, confidence of patients and confidence of the membership organisation, which is what a CCG is.

‘So we need to build those safeguards in. But I think that is eminently doable, and it is not therefore going to be an impediment to that.’

Dr Mike Dixon, interim president of NHS Clinical Commissioners, agrees. He says: ‘Conflicts of interest are a big issue, but the bigger issue is the NHS staying as it is.

‘A CCG is made up of its local GPs, so will be moving in the same direction as its frontline GPs – so having control of the budget that pays for primary care will enable them to get the best out of it.’

Dr Dixon points to the issue of funding to improve GP premises being ‘pretty much at a standstill’, and says it could be improved by CCGs taking over this funding from NHS England.

Indeed, Pulse has learned that NHS Blackpool CCG has asked NHS England for the right to hold the GP premises budget, in a bid to be able to direct urgently needed funds to support out-of-hospital care.

For Dr Dixon, the move to local contracts is ‘inevitable’. He says: ‘What we are seeing with Somerset is the first flow of water through the floodgates. It is the breaking down of the centralist command-and-control system, which is not particularly sensitive to what local patients want and what local clinicians feel they should be providing. It is very significant indeed.’

Pulse October survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens