As part of our celebration of the history of Pulse and general practice, we are looking at some of the big issues of the last 64 years. Sofia Lind analyses the history of threats of industrial action

Last year, the BMA’s GP Committee silently abandoned plans to ballot the profession over the 2023/24 contract imposition. And this was hardly the first time in the last decade that talks about action came to nothing-at-all.

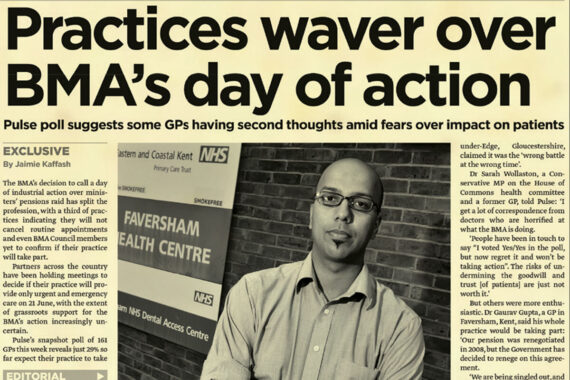

Barely a year goes by without some talk of GP industrial action. Yet for all that talk, GPs have only taken part in a full walkout from services once, in 2012 in the BMA’s unsuccessful doctor-wide strike over pension reform.

‘At the time, it felt like a pivotal moment,’ says Pulse’s then editor Steve Nowottny.

‘For the first time since 1975, thousands of GPs and other doctors were finally downing tools. After decades of keeping their powder dry, the BMA had opted for industrial action.’

However, ‘on the eve of the protest’, he says ‘Pulse investigated how many practices were actually planning to join it – we found just one in four had notified their primary care organisation that they would be taking part.

‘Our story soon became huge news nationally. “GPs: We don’t want to strike”, declared the front page of the Daily Mail.

‘The day of action hadn’t become a damp squib, exactly – but its limitations had become painfully clear.’

Then health secretary Jeremy Hunt had a free path to implementing the pensions reforms, which left many out of pocket. It was only in 2022 that the Government acknowledged that the system was broken with doctors ending up out of pocket to work, due to pensions tax rules.

Threats of mass resignation

While threatened walkouts have rarely had success, one form of threatened actions have brought about positive changes – the threat of mass resignations of GPs.

In 1966, then-GPC chair James Cameron was given leverage to negotiate the ‘GP Charter’ after 17,000 out of a total 19,000 GPs submitted undated resignations to the BMA.

This brought GPs dedicated premises and expenses funding for the first time, having previously been largely managed by GP husbands and their wives out of residential backrooms.

Longstanding GPC member Dr Peter Holden says: ‘That stopped us being a cottage industry and moved us into the 20th century.

‘It was arguably very successful and in fact the only reason things have gone wrong from there on in has been the Government interfering with the [Review Body on Doctors’ and Dentists’ Remuneration] recommendations.’

Also successful – although seemingly largely forgotten – was a 1974 mass resignation collection by the BMA which did bring about an uplift to GP funding.

The same threat was bandied about in 1989, but was again ultimately unsuccessful when then-health secretary Kenneth Clarke imposed a reformative GP contract on the profession that introduced fundholding.

GP leaders remembers this as ‘divisive’ for the profession, with those who took up fundholding finding themselves in a privileged position compared to those who opposed the move on various grounds, including refusing to be financially incentivised not to refer patients to hospital.

Next up was 2001, when to the nuisance of the Government the BMA passed a ballot to collect undated resignations – in protest over workload – just ahead of a general election. But even then-members of the GPC have forgotten that the threat was there as it ‘never came to fruition’. However, the general unrest of the profession at the time was undeniable, and Tony Blair’s Government was eventually forced hike GP funding via the pivotal 2004 contract.

Are we set for more threats of action?

Dr Richard Vautrey, GPC chair between 2017-2021, argues that because of the ‘folklore’ of the successful mass resignations of 1966, the ‘suggestion comes up now and again’.

There are good reasons that GPs are less likely to take action than their secondary care counterparts.

Dr Chaand Nagpaul, who chaired the GPC from 2013-2017, says: ‘In general practice, we have GP contractors, we have salaried GPs, we have independent GP locums, we have portfolio GPs and they’re all working within different contractual spaces, which is very different from the employed status of hospital doctors on a specific salary scale.’

Despite this, GPs can take action without striking, for example by moves to put limits to manage their own workload, he argues.

‘I think we are at a watershed moment where the GP progression is at its lowest ebb that I can remember since 2004. Actually, that was the last time I remember the profession being at such a low ebb, and then we saw the new contract.’

‘But I think the positiveness is that something has to be done. It really does. And I believe that actually we have come to that point we been at before 2004 where we need, the nation needs, a renaissance in general practice.

‘And it really is up to our representatives on the GPC, leadership of the profession, to really call for that to happen.’

Dr Vautrey says: ‘You need to use threats that you can follow through. Taking industrial action, for GPs, is an extremely difficult situation to put people into, for a variety of reasons.

‘Certainly, within my time we always sought to highlight to government, as effective as we could, the problems that we were facing, achieve changes in investment through negotiation and challenge as much as we were able to. But ultimately you need a government that is prepared to listen and engage.’

Dr Holden also highlights how difficult it is for GPs to stage industrial action, but he thinks an ‘explosion’ of general practice is nigh due to underfunding that will sharpen the Government’s mind if GPC cannot.

‘I think what has to happen is there has to be a very serious renegotiation of the GP contract, and it has to be quick,’ he says.

Current GPC chair Dr Katie Bramall-Stainer used the recent England LMC conference to urge GPs to give negotiators the backing they need in contract negotiations by showing that they would be willing to take action.

And although the last decade shows she is facing an uphill battle, history is not void of examples where GPs have successfully put their foot down.

If someone’s able to do it, it may just be Dr Bramall-Stainer.

Dr Holden says: ‘She’s talking the talk, and she’s walking the walk as a GP every day of the week.’

Pulse October survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens