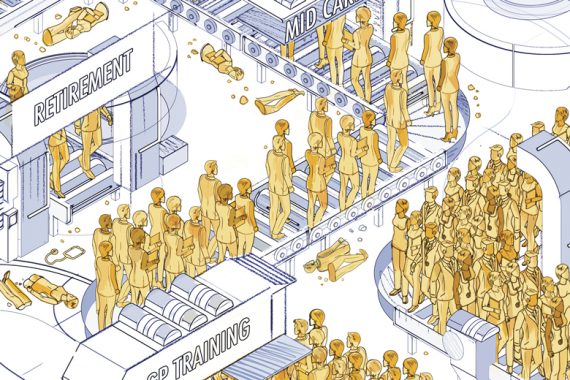

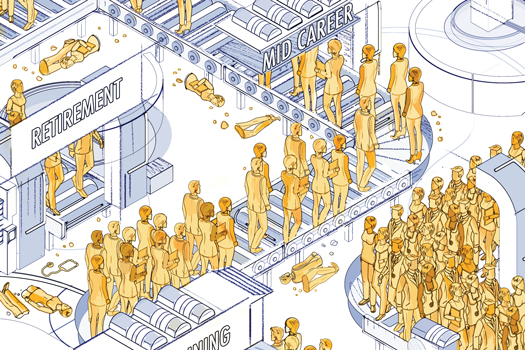

The GP workforce’s faulty production line

The year is 2024. The GP workforce boasts 6,000 more doctors than a mere five years ago and Matt Hancock is the unlikely hero of general practice.

Unfortunately, such a scenario is about as unlikely as his predecessor Jeremy Hunt’s infamous ‘5,000 extra GPs’ pledge – which translated into the loss of 1,000 GPs over his tenure.

There are green shoots. Health Education England has been successful in increasing the number of medical graduates entering general practice. And the full NHS People Plan should finally be published this month, detailing exactly how the Government plans to recruit and retain the GPs needed to reach its targets.

But a Pulse analysis of official workforce and training statistics reveals ministers face a gargantuan task.

To sum up the scale of the problem, the latest NHS Digital data reveal a net loss of 489 qualified full-time-equivalent doctors between September 2018 and September 2019. Projecting this over the next few years suggests that by the start of 2024/25, the Government will actually have 1,869 fewer fully qualified FTE GPs than in 2019.

And the current success in recruiting at specialty training level will only go so far towards meeting the targets, unless NHS England can persuade more of these trainees to take full-time roles when they qualify than is currently the case.

But the key tasks will be stemming the catastrophic drain of middle-aged GPs from the profession, and coaxing overseas GPs to the UK. Both will be much easier said than done at a time when archaic pension tax rules are forcing GPs to retire early and Brexit is deterring potential overseas recruits.

The promise of 6,000 new GPs by 2024/25 was made in the build-up to last December’s election. The figure was reached using characteristically creative accounting; the Government said only half will be fully qualified by 2024/25 while the other half will be trainees.

But there remains little detail. We know there is to be a £2.5bn investment over the next four years to help retain GPs, a pledge to recruit more from overseas and an aim to train 500 more GPs a year.

And the health secretary told Pulse in November of his plans to reduce ‘a whole load of the bureaucracy’ that acts as a barrier to international GPs, to tackle the punitive pension tax system and to provide ‘financial rewards’ to boost retention. He did not, however, specify whether current financial incentives would actually be expanded and while he acknowledged that reducing workload was the key to retaining GPs, he gave scant detail of how he would achieve this.

Of course, Mr Hancock isn’t the first health secretary to talk big on GP numbers. Back in 2014, his predecessor Jeremy Hunt made his doomed pledge to ‘train and retain an extra 5,000 GPs’ by 2020, to boost retention and increase overseas recruitment. But by 2020, GP numbers had in fact fallen by 1,000.

Recent training figures do represent some success. Last year, 3,500 graduates entered GP specialty training – the most ever. But this will only go so far.

Using data from UCAS, HEE, NHS Digital and the Department of Health and Social Care, alongside modelling from think-tank the Nuffield Trust, Pulse can reveal that despite a record intake of GP trainees for the second consecutive year in 2019, this cohort is projected to deliver only around 1,000 more FTE GPs than we had when Mr Hancock made his pledge in 2019 (see charts, below).

Pulse’s analysis found there were 3,019 in the 2016 GP training cohort. Yet, there were only 1,931 GP ‘joiners’ under the age of 45 in 2019. This suggests every 100 GP trainees leads to 65 FTE GPs. Indeed, NHS England director of primary care Dr Nikita Kanani puts this figure closer to 40 FTE GPs.

This low conversion rate is partly due to a greater desire for portfolio working. Co-chair of the BMA’s GP trainees subcommittee Dr Sandesh Gulhane, who qualified as a GP in October and works across A&E, out-of-hours services, general practice and a football club, explains why the new generation of GPs find a flexible career so attractive.

‘People want the flexibility to have a life’, he says. ‘That’s a good thing, because otherwise you’ll see a huge amount of burnout. There’s no point in GPs working flat-out and then after 10 years saying “I’m done”. I’m a locum and I see the partners and think “I don’t want to do that”. I’d rather earn a bit less and have a bit more family time. We need to make partnerships more attractive and overhaul our training system. It’s not fit for purpose right now.’

‘Uncertainty over the past three years has put a halt to EU recruits’

Dr Kieran Sharrock

But convincing younger GPs to take full-time roles may be the least of the Government’s worries. The major problems come mid-career. Data from NHS Digital show a net loss of 340 GPs in their 50s between September 2018 and September 2019. This suggests 1,200 GPs in this age group could be lost by 2024.

According to GP Survival chair and pensions expert Dr Nick Grundy, many GPs in their 50s are opting to retire early as they are ‘really sick’ of reorganisations, bureaucracy and backbreaking workload. Indeed, he says he knows of many who are using their next revalidation as a marker for when to retire.

The pension tax rules have also led many, Dr Grundy included, to reduce their sessions. The launch of a review shows a recognition of the problem but, as Dr Grundy points out, it will be meaningless without the right outcomes.

Naturally there is a knock-on effect of even greater workload for the GPs who remain – leading to a greater chance that they too will leave. So, with both retention and domestic recruitment posing major problems, overseas recruitment might seem to be a quick fix.

In 2017, NHS England said two-thirds of Mr Hunt’s 5,000 GPs could come from overseas. The latest available data make a mockery of this: the international recruitment scheme has yielded only ‘over 150’ GPs to date, primary care minister Jo Churchill admitted in October.

Lincolnshire LMCs medical secretary Dr Kieran Sharrock, who ran a successful pilot of the national overseas recruitment scheme in 2016, says NHS England has not learned lessons from his pilot, which offered overseas GPs an intensive three-month language course, covered their living costs, and promised a job offer if they reached the required standard. ‘What we did costs less than training someone to be a doctor’, he says.

The UK’s exit from the EU is another factor. Dr Sharrock says in 2016/17, a number of doctors from across Europe were ‘very keen’. But he adds: ‘The uncertainty over the past three years has put a halt to people wanting to come.’

The magnitude of the task ahead has left many GPs wondering whether a new approach altogether is needed.

Lancashire and Cumbria LMCs chief executive Peter Higgins says: ‘General practice needs to be a good place to work, it’s got to be professionally rewarding and offer new doctors what they want.

‘Until we’ve tackled the basic pressures within general practice it’s hard to have any confidence that doctors coming out of training will stay in general practice and stay in this country.

‘The Government needs to scale back its expectations of general practice and be realistic. We need to stabilise what we’ve got now before we move forward.’

Case study – ‘Reducing my working week to five sessions has saved my sanity’

I’m coming up to my 58th birthday this year and I’ve been in my practice for about 25 years since finishing GP training.

About three years ago, my pension pot was full so I took the decision to reduce my hours. It was part of succession planning because it enabled us to invite our current retained GP to become a part-time partner, but also something to help me start seeing a bit of light at the end of the tunnel. I was just getting so thoroughly jaded.

If the pension cap hadn’t been in place then I may well have tried to continue as a full-time partner, but I recognise that it was just becoming more and more of a struggle for me. Reducing my working week to effectively five sessions has certainly saved my sanity.

I’m not too sure what mechanisms can be put in place to help younger GPs

I was a GP trainee in 1990 when the then new contract came in and what’s frustrating is that every couple of years there seems to be yet another change. This latest PCN draft specifications debacle is a perfect example of that, I think that’s why it’s generated such a heated response.

I had a weekend away recently meeting up with old college friends – both hospital based and primary care – and we were all bemoaning the fact that the service we’re working in now is not as enjoyable as we thought it would be when we started.

I’ve got friends working not far from me who have set up extremely good practices in challenging areas who were quite invigorated by PCNs, but the stuffing’s been knocked out of them. One is definitely going to be retiring but needs to hang on until she’s able to attract a clinical partner into her practice. The PCN draft service specification document has been the final straw for a lot of people.

All these frustrations just mount up and I do feel for my younger colleagues. I’m not too sure what mechanisms they can put in place to ensure their resilience to carry on until whatever ridiculous age it is they will be able to retire.

Dr Louise Davies is a senior GP partner in Cheshire

Our full methodology for this feature is here

Pulse October survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens