Clinical conundrum: Managing a patient with Bell’s palsy

Former GP Dr Simon Lowe explains how to manage this acute case of Bell’s palsy in a pregnant woman, including how to do a proper examination, the importance of prompt treatment and when referral might be required.

A 34-year-old female patient attends your emergency surgery in some distress. She is 32 weeks pregnant, is usually well and is on no medication. She noticed that morning that the right side of her face seemed ‘odd’ and in the ensuing few hours the same area has become weak. On looking in the mirror she could see obvious droop on the right side and is concerned she might be having a stroke. You decide she probably has Bell’s palsy.

1: What is thought to be the cause of Bell’s palsy, and what other potential causes of facial palsy should we consider? In particular, how can we be confident about reassuring her that this is not a stroke?

Bell’s palsy is an idiopathic, usually unilateral, acute lower motor neurone facial palsy (FP). It is commoner in pregnancy, particularly in the third trimester and in the 7 days following delivery. Hilsinger and colleagues found a three-fold increase in frequency of Bell’s palsy (Bp) in pregnancy.

Evidence suggests that Human herpes virus 1 is a factor. However, physiological changes in pregnancy are also thought to play a role, such as hypercoagulable state, hypertension, fluid retention, impaired glucose tolerance, increased cortisol levels, immunosuppression and increased susceptibility to viral infection. An association with pre-eclampsia has been suggested. Bell’s is the commonest cause of FP, affecting about 37.7 individuals per 100,000 per annum.

Bell’s palsy arises because of inflammation of the facial nerve as it travels through its narrow canal in the petrous temporal bone. The resultant oedema and compression is responsible for the clinical features.

It is a diagnosis of exclusion, requiring the clinician to rule out several important differential causes. A thorough assessment is therefore mandatory.

To exclude a stroke, we must firstly identify if the FP is upper motor neurone (UMN), with sparing of the forehead muscles, or lower motor neurone (LMN), affecting all the facial muscles. The UMN lesions avoid paralysis of the forehead because of the dual UMN nerve supply to these muscles. (Rarely a dorsal pontine infarct can masquerade as a LMN palsy.) Additional neurological symptoms should support the correct diagnosis – eg, stroke or alternative neurology such as multiple sclerosis.

Having confirmed the likely presence of a LMN palsy, with absent forehead movement, the clinician will need to explore alternative differentials. A detailed history, for a more prolonged onset or other features should exclude a local tumour, infection or alternative neurology. If there is any doubt as to whether the diagnosis is an UMN or LMN lesion, a specialist opinion should be requested immediately.

Features indicating Bell’s palsy are shown in Box 1 and Image 1 shows typical facial appearance. Pregnant women are more likely to develop complete paralysis, which has a worse prognosis. Significant, burning pain, vertigo and deafness may suggest Ramsay Hunt syndrome (RHS), caused by shingles affecting the geniculate ganglion. A shingles rash is not always present at the outset with RHS, so have a high index of suspicion. Lyme disease can present with FP, which can be bilateral. It is the commonest cause of acute onset FP in children.

Box 1. Classic features of Bell’s palsy

History

- Sudden onset (within hours) of symptoms.

- Peak onset of symptoms within 1-3 days.

- No preceding history of trauma, recent surgery, localised infection.

- May have preceding prodromal illness.

- May note increased loudness of noise, taste changes and dryness of the eye (indicate pre-stapedial pathology).

- Difficulty raising the brow, blinking and closing the eye, smiling and pouting the lips, watery eye, oral incontinence.

- Change in speech and facial appearance.

Physical examination

- Cranial nerve examination normal except VIIth nerve function: Loss of frontalis function and forehead involvement (lower motor neurone lesion)

- Difficulty/inability to close the eye with weak orbicularis function (open the eye against resistance).

- Ask the patient to raise the brow, smile, pout their lips.

- Note oral incontinence, speech changes (differentiate from CVA related speech changes).

- Look for rash/pain over ear (Ramsay Hunt syndrome).

Image 1. Patient with Bell’s palsy which developed at 41 weeks of pregnancy; image taken at 2 days after onset of symptoms. Published with permission.

2: What is the acute management and how is this affected by the patient being pregnant? Is there any role for antivirals?

Our patient is 32 weeks pregnant. She is likely to be anxious, firstly about her Bp and the risk of permanent disability, but also about potential harm to her developing baby, or herself, of any medication.

The severity of FP may be assessed by the Sunnybrook scale. The worse the FP, the worse the prognosis. Early treatment, within 72 hours, is crucial. Around 90% of those treated for Bp with steroids within 72 hours will have a full recovery. This drops to 70% in those who are not treated with steroids within the 72-hour time frame. The severity and prognosis of FP is worse in pregnancy.

The recommended treatment for Bp, presenting within 72 hours of the onset of symptoms, is prednisolone:

- 50mg daily for 10 days or

- 60mg daily for 5 days followed by a daily reduction in dose of 10mg (total treatment time of 10 days), if a reducing dose is preferred.

Drugs should be prescribed in pregnancy only if the expected benefit to the mother is thought to be greater than the risk to the foetus. Corticosteroids have been extensively investigated during pregnancy, usually relating to respiratory or dermatological conditions, indicating that they can be safely used in Bp, at similar doses. Monitoring for steroid side effects – including blood pressure and blood glucose – is particularly important in pregnancy.

The long-term effects of unresolved FP are life changing and include altered facial appearance, difficulty with speech, eyes, swallowing and inevitable psychological sequelae. A detailed, individualised, discussion around the pros and cons of steroid treatment is therefore necessary before prescribing.

Eye care advice is an essential part of the management plan. Assessment of complete eye closure is mandatory. The inability of the eye to close puts the cornea at risk of drying out. This can result in corneal abrasions with a threat to vision. Every patient should be given specific eye care advice on using regular ‘preservative-free’ eye drops by day and ointment at night, taping the eye closed at night and advice and safety netting regarding any inflammatory symptoms to avoid unnecessary complications. A red or irritable eye requires urgent ophthalmological referral.

There is no evidence to support the use of antivirals in uncomplicated Bp. However, it is essential to recognise that Ramsay Hunt syndrome, or other pathologies, may masquerade as Bp, particularly in the early stages. Prognosis for RHS is worse than that of Bp. A survey conducted by Facial Palsy UK of patients with residual FP following RHS revealed 50% had been diagnosed with Bp initially. It can be difficult to diagnose as the shingles rash may appear after the onset of FP or there may be no rash (Zoster Sine Herpete) in up to 30% of cases. If symptoms suggest RHS then antiviral medications like acyclovir, famciclovir or valacyclovir are generally considered safe and may be prescribed. However, it’s crucial to consult with a specialist and discuss the potential risks and benefits with the pregnant individual before starting any treatment. The BNF states that acyclovir is not known to be harmful although manufacturers do advise to use only when potential benefit outweighs risk.

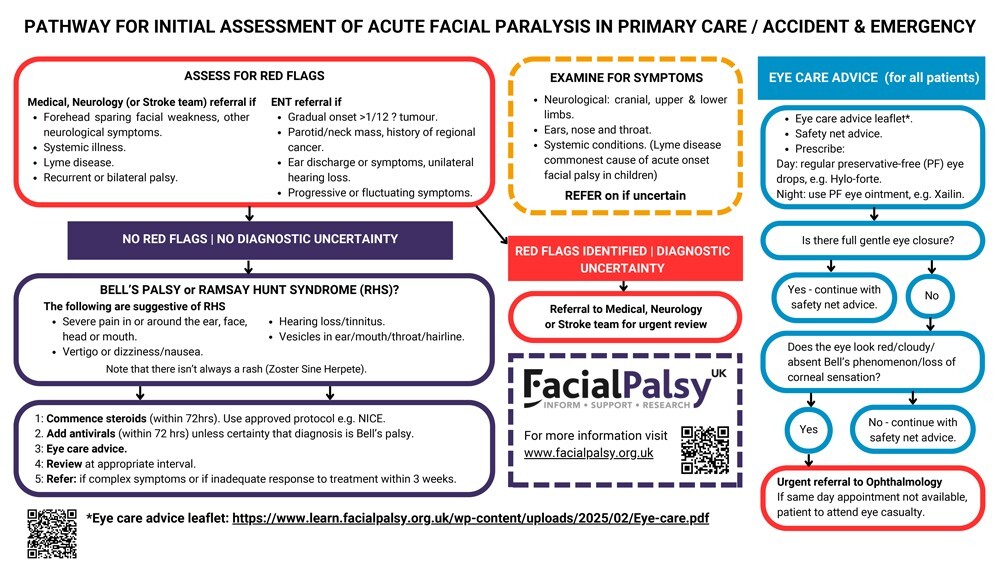

Figure 1 below outlines the key steps in recommended in the acute management of FP in primary care.

Figure 1. Pathway for initial assessment of acute facial paralysis in primary care or A&E

3: What complications might arise and how can we minimise the risk of these, or manage them if they occur?

Severity of FP is a key indicator of prognosis. Complete FP is less likely to recover than partial. The prognosis for a satisfactory recovery in pregnant women who develop complete FP with Bp is significantly worse than in the general population, with 52% recovering compared to 77-88% in a similar age non-pregnant population.

Persisting FP is a lifechanging diagnosis with difficulties with eye closure, speech, oral incontinence, smiling, blinking hyperacusis. The changes in speech and facial appearance adversely affect patient’s confidence, self-esteem and mood. Clearly this could be more significant in pregnancy. Appropriate emotional support should be offered.

An urgent referral to ENT or neurology should be considered if there is uncertainty regarding diagnosis, suspicion of red flags arises (see Figure 1) or if there has been no recovery within 3 weeks. If the cornea is at risk arrange an urgent ophthalmology consultation. Plastics referral is normally reserved for later complications such as synkinesis (abnormal movements) which are common and may be distressing. For patients who have made a partial recovery but are still suffering from symptoms referral to Plastics should be considered at around 3 months.

Remember that patient mental health is likely to be adversely affected and refer as appropriate. Care for residual FP should ideally involve a specialist Facial Palsy Team, including a specialist FP therapist. Sadly this is not available in all areas of the UK.

In summary, with a detailed assessment our patient has an excellent chance of a full recovery from what is a potentially very distressing condition. Early steroid treatment will improve prognosis but requires an informed discussion with the patient. Refer if there are any red flags or a failure to recover and be aware of the mental health effects of long-term disability.

Key points

- Bell’s palsy is commoner, and has a worse prognosis, in pregnancy.

- A full assessment is essential to avoid missing alternative diagnoses.

- Early steroids will improve prognosis.

- Refer patients if diagnostic uncertainty or if no recovery after 3 weeks.

Dr Simon Lowe is a retired GP in Bedford and member of Facial Palsy UK Medical Advisory Board, since contracting Ramsay Hunt syndrome in 2020.

With thanks to Mr Charles Nduka, Consultant Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, QVH, East Grinstead and Miss Philippa Moth, Consultant Obstetrician and Gynaecologist, Maidstone & Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust for their expert advice. Both are members of the Facial Palsy UK Medical Advisory Board.

Portfolio careers

What is the right portfolio career for you?

Visit Pulse Reference for details on 140 symptoms, including easily searchable symptoms and categories, offering you a free platform to check symptoms and receive potential diagnoses during consultations.

Related Articles

READERS' COMMENTS [2]

Please note, only GPs are permitted to add comments to articles

FP abbreviation is acceptable, given a context, but Bp only ever means ‘blood pressure’, not ‘Bell’s Palsy’. It didn’t even shorten the article, as ‘blood pressure’ then had to be written in full.

It is surprising how many will forget the simple supportive instruction of taping the eye closed overnight, usually because ot is not ‘medical treatment’ available on prescription, but something the patient has to be told to do themselves.

If the patient was my family member I would want an MRI, now thanks.

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2803956