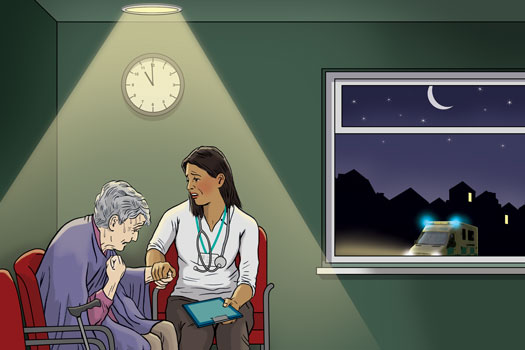

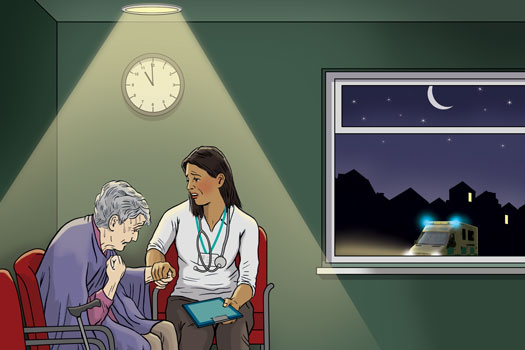

ambulance response times illustration 525x350px

Every GP will be required at some point in their career to make a life-or-death 999 call from the practice for one of their patients.

The process should run like clockwork. An ambulance arrives promptly, the paramedics safely transport the patient to hospital and give them the best chance of surviving.

But GPs are often living a different reality. GPs believe ambulance trusts are implementing unofficial policies to delay blue light assistance to practices in the mistaken belief that the presence of medical professionals and a defibrillator is enough to ensure patient safety.

Such policies exploit the fact that GPs are trained medical professionals. But they ignore the fact that while GPs are able to assess whether patients need emergency care, they are not equipped to provide urgent treatment. And these policies mean that GPs find themselves waiting for hours before paramedics attend.

A major Pulse investigation has revealed that these GPs’ concerns are correct – ambulance trusts across the UK are invariably taking more than double the time on average to attend calls from GPs compared with those made by the public or other services (see map).

It’s a nightmare position to be in as a GP. You don’t have the equipment or expertise and yet it would be expected that you would cope

Dr Zoe Neill

In some cases, such differentials are a result of protocols agreed with the healthcare professionals for ambulances to attend patients within one, two or four hours. But this doesn’t tell the whole story.

GPs have told Pulse of shocking examples, including cases where they have waited for more than an hour with patients suffering from myocardial infarctions, or sat with patients who had suspected sepsis for over 60 minutes. In one case, a patient with sepsis was made to wait three hours and the GP ran out of the oxygen they were administering.

GPs say they are not informed of how long the delay will be and are being put in the ‘outrageous’ position of looking after patients themselves – and deciding whether to drive them to hospital.

A recent Pulse survey shows that this situation is affecting the majority of GPs. Around 80% of the 733 GP respondents had experienced delays in ambulance call-outs to their practice. Just 16% said this hadn’t happened to them.

Dr Zoe Neill, a portfolio GP in Yorkshire, says a patient of hers died from sepsis after waiting 90 minutes for an ambulance at the practice. She adds: ‘It’s not clear whether the delay in getting them to hospital had an impact on the eventual outcome – but obviously it was way less than ideal.’

She considered taking him herself. ‘It’s a nightmare position to be in as a GP. You don’t have the equipment or expertise and yet it would be expected that you would cope with whatever arose. Imagine if he had arrested in my car on the 20 to 30-minute journey. It was an impossible choice.’

Now BMA leaders are taking a stand after such experiences. At a recent conference bringing together England’s LMC leaders, GPs called for action. They warned that family doctors were not trained to provide emergency care – but they were qualified to recognise an emergency.

Dr Matt Mayer, the BMA GP Committee workload policy lead, told delegates: ‘It’s absolutely outrageous that GPs are put in the position of having to look after incredibly unwell patients who need to urgently be in hospitals.’

There is nothing more terrifying for a GP than to be sitting with a seriously unwell patient watching them deteriorate

Dr Matt Mayer

Speaking to Pulse after the conference, he added: ‘GPs are neither equipped, trained nor resourced to provide the levels of emergency care these patients urgently need when an ambulance is called. It is a fundamental and cardinal law of medicine that if a doctor deems a patient to be in danger of imminent death or serious harm, then they should summon assistance immediately.

‘There is nothing more terrifying for a GP than to be sitting with a seriously unwell patient, such as a child, watching them deteriorate, hoping the ambulance will arrive in time, but knowing that they may die in front of them despite everything they are doing to help.’

He warns that data supplied by trusts to Pulse appears to show the downgrading of calls has become a normal approach and that this needs addressing urgently: ‘This is a practice that is putting patients at mortal risk and needs stamping out by NHS England and the Government immediately.’ Dr Mayer adds that following the LMCs Conference the committee will be working with the NHS to put a stop to the practice.

This situation partly arose because the presence of a GP and a defibrillator was enough to meet some targets set by the Government.

A letter to Dr Andrew Scott-Brown, vice chair of Hampshire and Isle of Wight LMC, from South Central Ambulance Service NHS trust and seen by Pulse, revealed that the trust implemented its own target of 15 minutes for a ‘category 1’ call where a GP and defibrillator were present – compared with seven minutes where no clinician was present.

I have been known to say to the family “you dial 999 and deny that I am here”

Dr Peter Holden

It was a similar case in Greater Manchester. Dr Amir Hannan, chair of the Association of Greater Manchester LMCs, says the LMC contacted the North West Ambulance Service NHS Trust about delays in ambulances. ‘We were told there was a problem with the pathway software and that calls that came from GP surgeries were being downgraded. However, I was told this had been updated as a result of my concerns.

‘Unfortunately, I’ve just heard recently that in Manchester……a similar incident happened with a child with asthma who was desaturating, an elderly person in their 70s who was having an MI. We have real concerns that someone is going to die unless we do something different.’

This situation regarding category 1 calls has changed. The Association of Ambulance Chief Executives (AACE) says the guideline on the presence of a GP and a defibrillator is no longer in use. A spokesperson says: ‘This change was made precisely to avoid the circumstances where a health professional calls for an ambulance but, because they had a defibrillator in their surgery, they effectively stopped the response time clock themselves. This wasn’t what was intended under the old policy but it was an unintended consequence.’

However, Pulse’s data shows that since April this has had little impact on the differing response times.

The ambulance trusts say that the figures received by Pulse may be skewed, as many trusts have implemented local protocols that allow the call operator and the GP to agree on a one, two or four-hour response time.

But Pulse’s analysis of some trusts’ data shows discrepancies in almost all categories of call. And Dr Peter Holden, a former GPC negotiator with an interest in urgent care, says that while agreed protocols used to work, the waits for ambulances are now so long that one or two-hour responses now seem a ‘luxury’. ‘We are now told it’s four hours – or longer.’

‘We do need to ensure parity of responses between public 999 and healthcare professional requests’

Association of Ambulance Chief Executives

To try and avoid long waits, Dr Holden says he uses a different approach: ‘If I am with a patient who needs an urgent ambulance I have been known to say to the family “you dial 999 and deny that I am here”. Because effectively there are two responses you get –the general public I’m-having-crushing-chest-pains immediate response, or four hours.’

The problems stem from the pressures faced by ambulance trusts. The regulator NHS Improvement published a report in September, based on a review chaired by Lord Carter, which found that 999 urgent and emergency calls have increased annually by 6% over the past five years. Demand is forecast to rise by at least a further 38% over the next decade, it said.

But GPs point out that these unofficial policies that delay ambulance responses to GPs are not the way to manage this demand, because GPs know better than most if an ambulance is necessary.

Speaking at the English LMCs Conference, Dr Sean Culloty, a GP in Cambridgeshire, said he had to wait three hours with a septic patient and ran out of oxygen: ‘I appreciate there are situations where patients could be safer in a GP surgery than elsewhere and this could be taken into account by the ambulance dispatcher. But when we see somebody who we think is really ill, they usually are really ill.’

The fault does not lie with the ambulance trusts, says Dr Culloty. ‘I have friends and family who work for the ambulance service so I am sympathetic to the enormous strain under which the current service works.’

Things may be changing, however. In a tacit acknowledgement that there are unofficial policies to respond to calls from healthcare professionals within different time frames, NHS England is trialling a new way of handling calls from clinicians.

Under a new framework for ambulance admissions for life-threatening and emergency calls, ambulance trusts would be ‘expected to respond to these requests under the same response levels as other 999 calls’, according to its policy document outlining the plans.

The AACE says it ‘categorically refutes’ allegations that calls from GP premises ‘are being deliberately downgraded’. However, it adds: ‘We acknowledge we do need to do better for healthcare professionals and ensure parity of responses between public 999 and healthcare professional requests, particularly for category 1 and category 2 calls.’

This new trial is an attempt to change the situation.

But Dr Holden disagrees the new system will bring about improvements: ‘Individual workloads are too high and there is no slack in the system. The bottom line is that there are not enough paramedics and not enough vehicles for the demand. Extra resources would help but people are working flat out.’

What GPs should do if an ambulance is delayed

Dr Caroline Fryar, the Medical Defence Union’s head of advisory services, outlines the medicolegal issues to bear in mind

Communication

Communicate to the ambulance service your evaluation of how urgently the patient needs to be transferred. Do not be pressured to change this unless the patient improves. Keep asking the service for regular updates of the arrival time.

Keep a record

Keep detailed notes of the incident and care provided. If a complaint or claim arises from emergency treatment you provided while awaiting a transfer to hospital, you can ask for support from your defence organisation.

Other insurances

If there are delays in the ambulance arriving, use your clinical judgment to decide whether it is more appropriate to get the patient to hospital in some other way, such as in your car. Consider potential issues, for example, further deterioration during the journey. Bear in mind that business and car insurances may have stipulations about this.

Emergency treatment

GPs have an ethical responsibility to offer help in an emergency, which could include urgent treatment while awaiting an ambulance. Such treatment is not classed as acting as a Good Samaritan, which is where a doctor provides emergency care when off duty as a bystander.

Pulse October survey

Take our July 2025 survey to potentially win £1.000 worth of tokens