How this PCN… brought in a health model from Brazil

This site is intended for health professionals only

A community health worker model made impressive changes in Brazil, so a GP practice teamed up with public health to implement it in a deprived area of London. After only a year, the impact has been major. Dr Cornelia Junghans-Minton, Dr Matthew Harris, Dr Saul Kaufmann and Dr Sheila Neogi explain

The Churchill Gardens estate in Westminster is a community with a high chronic disease burden and low levels of vaccination and screening uptake. There is a 17-year life expectancy gap between men living in areas like Churchill Gardens and those living 10 minutes away in affluent Belgravia.

To address these issues from a new angle, public health at the local authority and a GP practice drew inspiration from the Brazilian Family Health Strategy.

The vision came from Imperial College London’s reverse innovation research, which seeks to understand how ideas from lower income countries could be effectively translated to the UK. Community health workers (CHWs) exist in other countries, but it is the Brazilian model that holds the most promise.

Brazil’s CHW system has led to significant uptake in screening and immunisations, reduced hospital admissions and increased equity. It has also led to a rise in breastfeeding, improved child development and demonstrable reductions in mortality. It is cost effective because CHWs are trained lay community members. They build trusted relationships with households across a small area in a universal, comprehensive and integrated way. It is different from any other role in the UK health system.

Community health and wellbeing workers

In Brazil, CHWs live in the community they serve. Every month, they visit all the households in their area to build a relationship with the residents. They address their needs in a personalised manner, signposting to and connecting to services as needed. There is no discharge from or referral to a CHW. If you live in a neighbourhood covered by a CHW, they will knock on your door once a month, or more frequently if needed, to see how things are going.

To mirror the Brazilian CHW role, we looked for patients registered with the practice who were in Churchill Gardens. Four community health and wellbeing workers (CHWWs) were recruited from a pool of local community champions with a focus on empathy, a non-judgmental attitude, cultural competence and problem-solving abilities.

They were employed by the local council, each holding an honorary contract with the GP practice. Their training included introductions to key local services such as health visitors, care navigators, family navigators and social prescribers.

Each CHWW was given around 120 households to look after. The practice sent letters and text messages to the households to let them know who would be knocking on their door and what the service was about. The CHWWs wear T-shirts and fleeces with the CHWW logo and lanyards, so residents can identify them easily.

Building relationships

One year in, about 60% of residents have engaged with the CHWWs and engagement continues to increase. Crucially, once a relationship has been established, nobody has disengaged with the CHWWs.

Several important insights have emerged, including the discovery of people with high medical needs who do not visit their GP or A&E. We have also been surprised at some of the people struggling to access services. Importantly, the pilot has shown that the intervention is possible and acceptable to residents.

The project has already delivered significant impact. A quantitative evaluation of uptake showed households visited by a CHWW were 47% more likely to receive a vaccination and 82% more likely to have cancer screening and NHS health checks compared with homes that have not yet been visited.

We also found a decrease of 7.3% in unscheduled GP consultations in visited households compared with the previous year, while unscheduled consultations only decreased by 1% in those not visited.

Bridging gaps

CHWWs act as ‘glue’, creating bridges between the local authority, health services and the voluntary sector, drawing on these services as required. Relationships between CHWWs and the residents are enduring and trusted. They become a first point of contact in times of crisis and the CHWWs know how to provide just-in-time support.

Households may require support at any time so regular light-touch engagement is a must. Targeted health campaigns often fail because people may require multiple conversations or because other issues – housing, worries about children, antisocial behaviour or employment – are more of a priority.

As CHWWs provide support across the health and social care spectrum, they can help resolve households’ more pressing concerns, before returning to health conversations.

•During a monthly home visit, the CHWW noted that a 45-year-old man had not had an NHS health check. The resident listened to the information but wanted to talk about a housing issue. During a subsequent visit, he mentioned health issues and the CHWW encouraged him to see his GP. He ended up being investigated for prostate cancer. Months later, the resident asked about the health check because, following his cancer scare, he wanted to take better care of his health.

•The CHWW visited a family and learned that the 12-year-old daughter was missing a lot of school because she accompanied her mum to medical appointments to translate. The CHWW brought in help for the mother and met the daughter separately to talk about her mental wellbeing and support.

The trusting relationship also means they are well placed to learn about misconceptions. For example, a CHWW discovered some Muslim women declined cervical screening because in the countries they came from this service needs to be paid for. There was also a belief that married women did not need to worry about cervical cancer. However, being Muslim herself, the CHWW was able to address this.

As a result, GPs see fewer patients seeking help for non-medical problems, such as requests for housing letters. But at the same time, they see more people presenting with issues that were previously unknown to the practice because the patients would not normally make an appointment.

A scalable model

In Westminster, the model will expand to up to 25 CHWWs in areas of high need. It has also inspired two more pilots in London as well as in Yorkshire and Norfolk. And it has attracted the attention of the National Association of Primary Care (NAPC), which is championing a national roll-out. There is a CHWW apprenticeship scheme to standardise training and professionalism.

However, challenges remain.

Integration takes time and the CHWWs are only as good as the relationships they can build with the professionals around them and the help available. Clinical and pastoral supervision is key, providing psychological safety for the CHWWs.

And a sustainable funding solution is still needed. An initiative like this needs long-term sustainable funding to work. The longer the CHWWs work in a locality, the better they will be at building relationships and the more knowledgeable and skilful they will become.

In terms of value for money, the pilot cost about £90,000 in the first year with the majority being salary costs. Previous modelling shows that it would cost about £2bn per annum for every household in England to have a CHWW. But if the programme focussed only on the areas of highest need, this would be around £300m.

By starting in deprived areas, the impact on health inequalities could be profound.

The next step will be to demonstrate measurable impact on prevention, community cohesion, health literacy and wellbeing among the residents and to safely scale and implement a truly collaborative model on the ICS footprint. Imperial College London is hoping to carry out a trial to assess this.

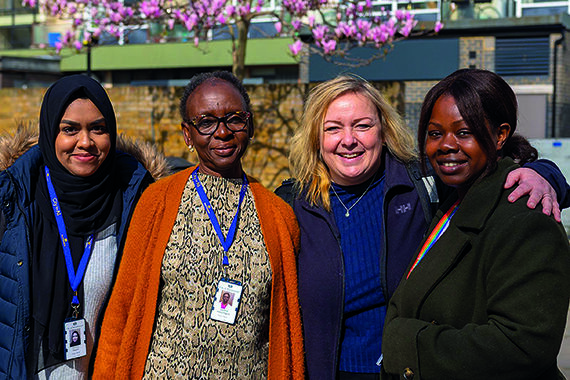

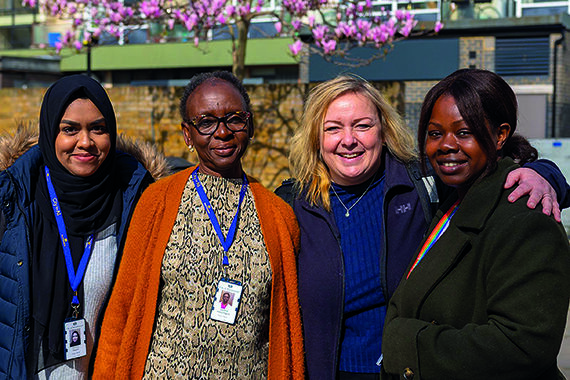

Image: From left: CHWWs Nahima Begum and Comfort Idowu-Fearon, Dr Cornelia Junghans Minton, and CHWW Maureen Katusabe